Even as the Fourteenth Amendment noted birthright citizenship for African Americans, and the Federal Government would recognize them as citizens, the Slaughterhouse Cases (1872) underscored a critical reality: the Supreme Court’s interpretations only carry the force of law when backed by the concerted action of the Legislative (Congress) and the Executive (President) branches.

This delicate balance between branches of government was laid bare during Reconstruction, as sweeping constitutional provisions guaranteeing civil rights for Black Americans could be narrowed—or even undermined—by judicial rulings if federal legislators and the president were unwilling or unable to enforce them.

From the Enforcement Acts (1870), aimed at curbing racial violence, to the legal disputes that culminated in United States v. Cruikshank (1875), the era’s most consequential clashes highlight how the SCOTUS' promise of birthright citizenship will continue to be tested repeatedly by the political will, or lack thereof, of those entrusted with shaping the nation’s future. The question becomes: what makes a United States citizen under the law?

The United States Constitution, drafted in the summer of 1787, is a document of declarations—of powers enumerated, rights implied, and a government stitched together from compromise. But on the question of citizenship, it is strangely silent. The word "citizen" appears in its text, but nowhere is it defined.

Who, precisely, belonged to the new republic? The Founders, preoccupied with balancing state and federal authority, left that question unanswered, which would haunt the nation for the next century.

The omission was no accident. At the time of the Constitution’s drafting, citizenship was less a matter of principle than of practice, inherited from the British legal tradition of jus soli, or the right of the soil. In 1608, Calvin’s Case established that anyone born within the dominion of the King was a subject of the crown. The American colonies had operated under this doctrine for generations. At independence, British-born individuals became Americans not by decree but by default. Their allegiance transferred from monarchy to republic. But the Revolution had rejected the old world’s doctrine of hereditary privilege, and perhaps did so with jus soli.

The Constitution offered no clarity. It listed requirements for officeholders—seven years of citizenship to serve in the House, nine for the Senate, and the Presidency—the cryptic mandate of being a “natural-born citizen.” However, the Constitution granted Congress the power to establish a process for naturalization but said nothing of those born on American soil.

In 1790, the First Congress of the United States took up the unfinished business of the Constitution. The question of citizenship, carefully avoided in Philadelphia three years earlier, demanded an answer. Who, in this new republic, could claim membership? The result was the Naturalization Act of 1790, a law defining what it meant to be an American for the first time. The answer was both sweeping and narrow: citizenship was open—but only to “free white persons.”

The law did not mention birthright citizenship. Instead, it introduced a different principle: jus sanguinis, which translates from Latin as "right of blood." This tradition in Roman law pertains to the principle that a person's nationality or citizenship is determined by the nationality or citizenship of one or both parents—inheriting their status not from the place of their birth but from their lineage.

The omission of jus soli—the long-standing British principle that birth on the soil conferred citizenship—was striking, suggesting that, in the Founders' minds, belonging was not merely a matter of geography but of identity. In the American republic, those who counted as Americans were not self-evident; it was to be determined by law, by Congress, and, crucially, by race.

Nowhere did that power of race in America appear more starkly than in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), when Chief Justice Roger Taney declared that Black Americans, free or enslaved, could never be citizens. He reasoned that the Founders never intended to include Black people in the political community, effectively erasing them from the nation’s legal order. It was a blow so severe that it helped propel the country toward civil war. Only after the Union’s victory did the Fourteenth Amendment, adopted in 1868, overturn Dred Scott, proclaiming that African Americans were born in the United States and "subject to the jurisdiction thereof"—under the paternalism of their former masters—were subject to no other jurisdiction.

This would become an apparent problem with the Mexican-American War and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo not only redrawn borders, but also redefined race. Under the Naturalization Act of 1790, only “free white persons” could become U.S. citizens. But in 1848, with vast new territories and thousands of Mexican residents now under American rule, the law posed a problem: Were Mexicans white?

The contradictions of race and citizenship played out in the lives of the Pico brothers of California. They were of mixed Native and African ancestry, wealthy landowners, influential politicians, and voting citizens. They held power in the city and state government, paid substantial taxes, and shaped the future of California. Yet, in the eyes of the law, they were white. Race, it seemed, was not just ancestry or appearance—because by appearance, Don Pío Pico fooled nobody, he was of not of Anglo stock, like most Americans of the time—but it was a legal designation, as fluid as it was strategic, defined less by lineage than by the shifting needs of the state.

To sidestep legal contradiction, the U.S. government granted citizenship to those it deemed citizens. Courts and officials classified Mexicans as white—on paper, at least—ensuring their eligibility for citizenship. It was a bureaucratic sleight of hand, a legal fiction born of necessity. However, as law made clear and lived reality confirmed, race was never just a matter of classification; it was a shifting line, drawn and redrawn with power, policy, and prejudice.

Throughout and after the Civil War, questions of citizenship and race continued to be brought before the courts. The Naturalization Act of 1870 emerged in the immediate aftermath of the abolition of slavery, its provisions echoing the promise of the Fourteenth Amendment by extending citizenship to “aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent.”

It was a notable departure from the restrictive language of the 1790 Act, which had limited naturalization exclusively to “free white persons. " In other words, it shut the door on nearly everyone else, leaving racial exclusions intact.

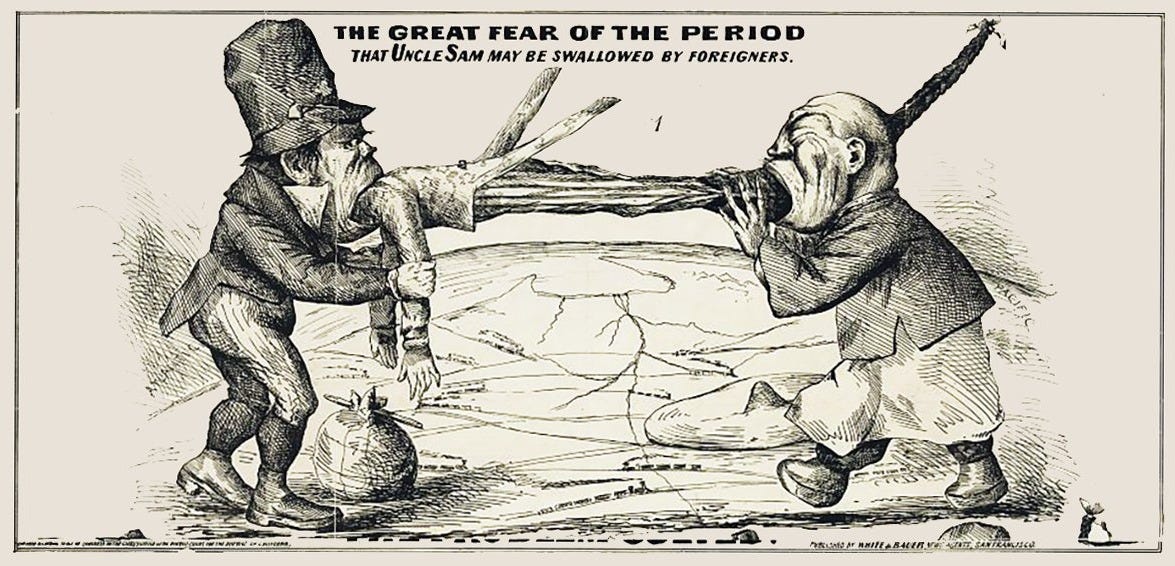

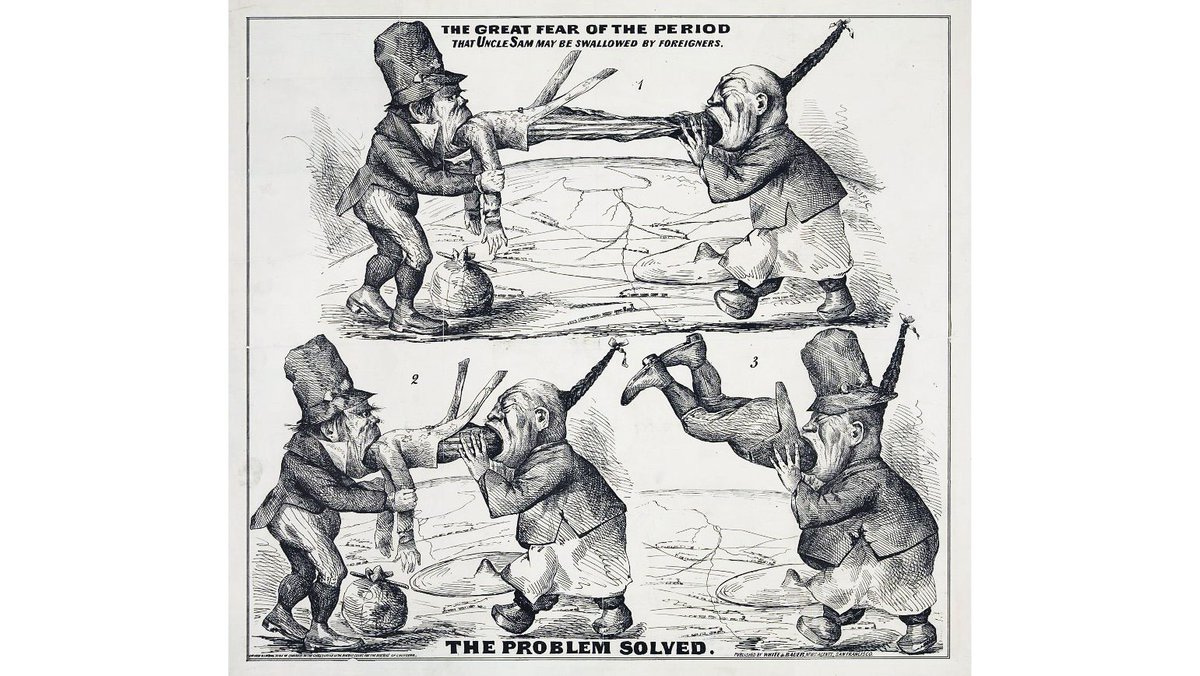

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) amid rising anti-Chinese sentiment. This stark declaration explicitly barred Chinese laborers from naturalizing as U.S. citizens, signaling the racial limits of American inclusivity at the time. Beneath it all, the machinery of naturalization remained steeped in familiar rituals: applicants had to reside in the United States for a set number of years, renounce foreign allegiances, swear an oath to the republic, and be recognized by the United States government as a citizen of the republic.

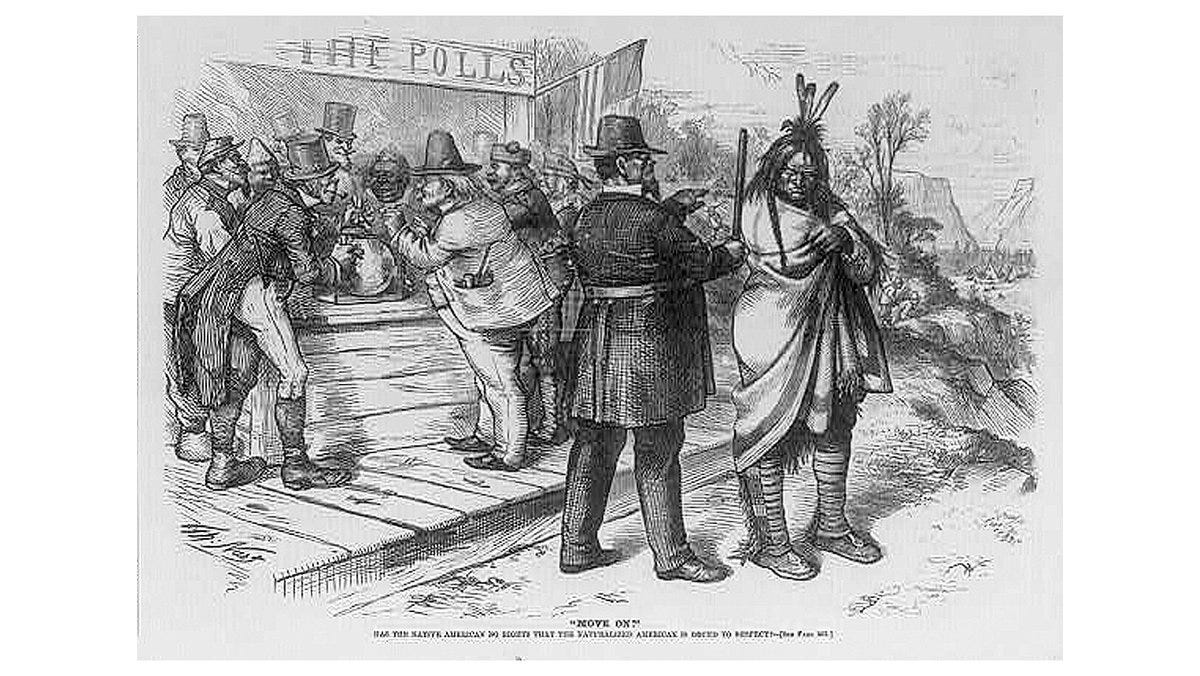

Proof of these exclusions was evident among Native Americans, as seen in Elk v. Wilkins (1884). John Elk, a member of the Winnebago (Ho-Chunk) tribe, decided to leave his reservation and settle in Omaha, Nebraska, believing he could carve out a new life—and cast a ballot—like any other American citizen. But when he attempted to register to vote, local officials refused, insisting he was not a U.S. citizen. Elk sued, arguing the Fourteenth Amendment’s birthright clause should cover him: he was born on American soil and had renounced his tribal allegiance. In 1884, the Supreme Court unanimously disagreed (9-0).

In an opinion delivered by Justice Horace Gray, the Court drew a line around the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof,” concluding that tribal members, by their birth into a sovereign nation within U.S. borders, were not wholly under federal jurisdiction as other native-born citizens were. The verdict stood as a stark reminder of the limited reach of Reconstruction’s grand promises: Native Americans would not be granted automatic citizenship simply by birth on U.S. land until Congress stepped in—jus sanguinis, the "right of blood," or the recognition of a citizen by the federal government remained the law. For Native Americans, it would take the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 to mend a constitutional gap that Elk’s case had so plainly exposed.

Now, the question of immigrants, specifically on the West Coast, was whether the Fourteenth Amendment included the children of immigrants. This situation was seen in the case of United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898). Wong Kim Ark, born on American soil in San Francisco to Chinese parents who were not recognized as citizens, left the United States for a brief visit to China in 1894. Upon his return in 1895, immigration officials refused to let him enter, citing the provisions of the Chinese Exclusion Act. Wong claimed citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment, with his lawyers arguing the jus soli principle, which, on its face, promised that “all persons born” within U.S. jurisdiction were citizens.

In a 6-2 decision, the Supreme Court sided with Wong, handing down an opinion by Justice Horace Gray that cut straight to the heart of the Fourteenth Amendment’s birthright guarantee. “Subject to the jurisdiction thereof,” the Court declared, excluded only children of diplomats and hostile occupiers, not the offspring of lawful residents. Thus, the justices interpreted the law as jus soli—the principle that to be born on American soil is to be an American.

For many, United States v. Wong Kim Ark has been regarded as the cornerstone of birthright citizenship. What is the problem with this? The United States federal government has hardly recognized this interpretation. How do we know this? If this were the case, the Fifteenth Amendment, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged…on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

The Chinese population was not allowed to vote until the Magnuson Act (also known as the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act) was passed, which allowed for the entry of Chinese immigrants as citizens (with a total of 105) with voting rights, officially declaring them naturalized citizens. It has been interpreted as removing the racial barrier to voting at the federal level, but the United States already had the Fifteenth Amendment for that purpose. The only logical conclusion is that the federal government has never recognized jus soli, only jus sanguinis, in its federal law.

In 1906, this happened for other non-Chinese groups with the Basic Naturalization Act. The Act sought to standardize naturalization procedures nationwide, ensuring the process was consistent, transparent, and less susceptible to corruption or misunderstanding. To oversee this process, the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization was born.

In 1924, the Johnson-Reed Act, a legislative manifestation of the era's nativism, established quotas based on national origins, significantly curtailing immigration from outside Northwestern Europe. The act also left the racial bars on naturalization untouched.

This means the question of who is an American can never rest. It is a story still being written, an argument that resurfaces whenever the nation feels the tremors of change as generations fight—again and again—to stake their claim to a republic built on the promise of liberty and justice for all or of a policy that valued family reunification and individual skills? This heralded a new chapter in American immigration history, where the promise of inclusivity began to align more closely with the nation's founding creed.

But by then, decades of racial exclusion had made clear that citizenship—birthright citizenship has yet to be officially legislated. This leaves us with numerous historical questions:

Does birthright citizenship stand on shaky ground?

Never codified by statute, does its reliance on a single successful SCOTUS case (United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 1898) open the debate to a contemporary reinterpretation?

No matter the political result, the question of who an American is can not yet rest. It is a story still being written, an argument that will continue to resurface until settled by Congress and the POTUS signs birthright citizenship into law, and to stake a legal claim to the citizenry in a republic— built on laws that protect the promise of liberty and justice for all.

Note: All sources are linked inside the article.