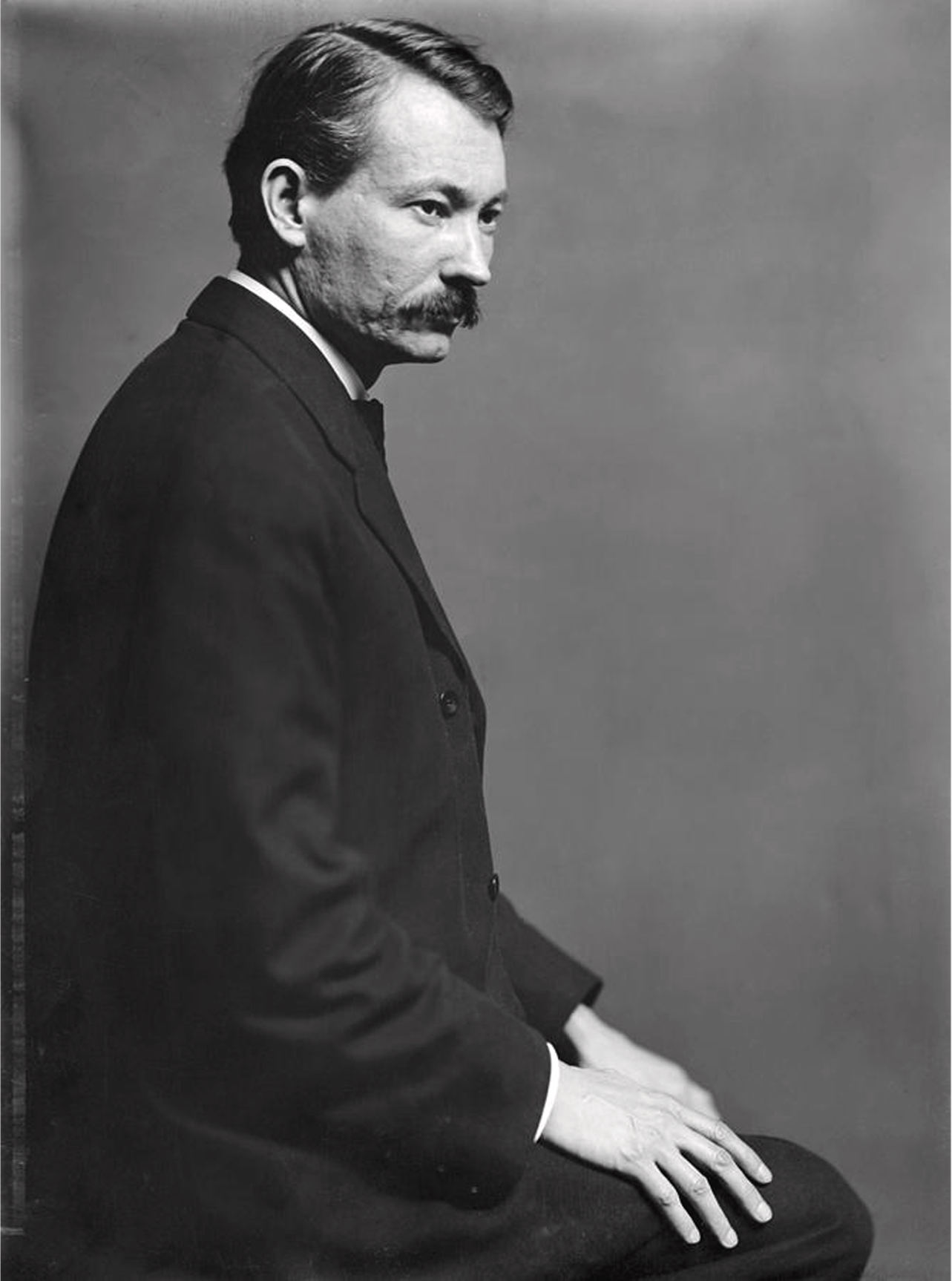

A Sculptor’s Odyssey: The Journey of Charles Cristadoro

Hollywood Through the Eyes of Charles Cristadoro, Vol. IV

In the heart of St. Paul, Minnesota, where the Mississippi River carves its quiet path, a young Charles Cristadoro first set his hands to the tools of art, studying at the city’s art school with a fervor that belied his years. Yet, it was not merely the classroom that shaped him; Cristadoro was a wanderer, his spirit drawn to distant horizons. If given his druthers, he once confessed, painting would have been his truest voice, the brush his chosen instrument of expression.

The walls of his family home, adorned with a collection of artworks that whispered of beauty and ambition, surely stirred the young artist’s soul, planting seeds that would blossom into a lifelong devotion to creation. Not all his triumphs, however, were bound to the chisel and stone. In a moment of quiet victory, Cristadoro claimed a $10 third-place prize for his sketch Girl Seated in a contest held by the Art Workers Guild in St. Paul, a testament to his versatility, even in youth.

But it was sculpting, not painting, that seized his heart early on. His friend Bob Baker recalled how Cristadoro, reflecting on his formative years, spoke of Chicago as the crucible where his passion for sculpting was forged. In 1893, at the tender age of twelve, Cristadoro found himself amid the grandeur of the World’s Columbian Exposition, a spectacle that would alter the course of his life. There, amid the clamor and ambition of that great fair, he worked on “great big hands,” sculpting monumental forms that demanded not just skill but a communion with the senses—the touch, the feel, the sheer scale of creation. These experiences, he later said, bound him irrevocably to his craft.

The Exposition was no mere carnival; it was a beacon of American aspiration, a stage where the nation unveiled its dreams to the world. Electricity, that marvel of the age, lit the night sky, allowing festivities to stretch beyond the constraints of daylight. Giants of invention, Nikola Tesla and Thomas Edison, stood as rivals in this electric theater, while Elias Disney, a carpenter drawn to Chicago’s promise, carried stories home that would ignite the imaginations of his sons, Roy and Walt, whose own dreams would one day reshape the world’s stories.

Just beyond the fairgrounds, Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show spun tales of the frontier, planting seeds in the minds of children who would play cowboys and Indians for generations. For young Cristadoro, immersed in this cultural maelstrom, the Exposition was not just a backdrop but a forge, shaping his vision and his place in America’s unfolding narrative. In St. Paul, Cristadoro’s life intertwined with Aloys Bohnen, known to friends as Al, a man whose roots ran deep in the Minnesota soil. The two became fast friends, joined by a shared passion for art and a studio they would later keep with another artist friend, Blanding Sloan.

Al, a figure of charm and ease, was known for hosting spaghetti dinners that left pots in glorious disarray, as a family member fondly recalled. Yet, beneath his genial exterior, Al carried a certain detachment, a “bland fatalism” that lent his work an enviable looseness but, some felt, lacked the fire of true purpose. “He certainly is a very attractive fellow,” a relative mused, “but there you have it. You can’t beat the game! If you lead a purposeless life, you’ll do purposeless work.” Al, it seemed, sought not to conquer the heights of art but to dance lightly through life, a choice both admired and lamented for its squandered potential.

Cristadoro’s path led him next to Cincinnati, where he honed his craft under the tutelage of Clement Barnhorn at the Art Academy. Barnhorn, a renowned sculptor, guided Cristadoro in the art of modeling, refining the raw talent of a young man destined to leave his mark. From Cincinnati, Cristadoro returned to his native New York, where he immersed himself in the vibrant artistic currents of the city. There, at the Old Chase School, he studied under masters like William Merritt Chase, Fredrick DuMond, F. Luis Mora, and Robert Henri—teachers whose influence would ripple across American art.

These were no ordinary instructors; they were the vanguard of a generation that would spark artistic revolutions, particularly in the burgeoning cultural hubs of Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Diego, where Cristadoro and his peers would help forge vibrant art communities. William Merritt =, born in 1849 in rural Williamsburg, Indiana, was a titan of American art, his thirst for beauty unquenchable. From St. Louis to Munich’s Royal Academy, Chase’s journey was one of relentless pursuit, culminating in his return to New York in 1878 to teach at the Art Students’ League. A founder of the American Society of Painters in Pastel and the Chase School of Art (later Parsons The New School for Design), he was a mentor to Cristadoro and countless others.

Alongside Robert Henri, with whom he likely crossed paths at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Chase shaped a generation of artists, including Cristadoro, who absorbed their lessons in drawing, illustration, and painting. Al Bohnen, too, joined Cristadoro in New York, studying under Henri for four years, their bond strengthened by sun-soaked outings to Rockaway Beach, where friends returned sunburned but joyful.

In New York, Cristadoro refined his sculpting, mastering the delicate art of marble cutting. His skill drew the eye of Gutzon Borglum, the sculptor whose name would become synonymous with Mount Rushmore. Their connection may have been forged through Cristadoro’s father, who shared mutual friends with Borglum in Elbert and Alice Hubbard, luminaries of the Roycroft movement. The Hubbards, tragically lost aboard the RMS Lusitania in 1915, were titans of influence, their sinking a spark that ignited American resolve in World War I.

If not through the Hubbards, Cristadoro and Borglum likely met before 1909, when Borglum kept a studio in New York, a city alive with artistic and political ferment. Borglum, born in 1867 in Bear Lake, Idaho, had carved his path from a portrait of General John C. Fremont in 1888 to friendships with Theodore Roosevelt and Auguste Rodin. His work, defined by the “emotional impact of volume,” found its ultimate expression in Mount Rushmore, where he immortalized Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt. Yet Cristadoro, faced with a choice, turned away from Borglum’s monumental vision. He chose family over fame, returning to live with his mother, father, and sister, Agnus.

Described as “very quick and smart and an enthusiastic stamp collector,” Cristadoro’s eccentricity only deepened with time, a trait that would define his singular path. His life was not one of towering monuments but of quiet, persistent creation, a testament to the artist’s unyielding devotion to his craft and the bonds that anchored him. In the end, Charles Cristadoro carved not just stone but a legacy, one shaped by the places he wandered, the mentors who guided him, and the friendships that sustained him.

American Federation of Arts. American Art Annual. Edited by Florence N. Levy. Vol. 5. New York: American Art Annual, 1905–1906.

Baker, Bob. Interview by V. P. Romo. Discussion of Charles Cristadoro, Los Angeles, CA, June 24, 2011.

Bohnen, Arthur. The Bohnens. August 19, 1974. http://www.dennisgoodno.com/Bohnen%20History/index.htm.

Boston Philatelic Society. An Historical Reference List of the Revenue Stamps of the United States: Including the Private Die Proprietary Stamps. Boston: Salem, Press of Newcomb & Gauss, 1899.

Coulter, Mary J. “Miniature Sculpture by San Diego Artist Shows Consummate Skill.” San Diego Union, May 1926.

Hoyle, John T., and Elbert Hubbard. In Memoriam: Elbert and Alice Hubbard. East Aurora, NY: Roycroft, 1915.

Library of Congress. The Lusitania Disaster. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/rotogravures/rotolusit.html.

PBS Online. “People and Events: Gutzon Borglum, 1867–1941.” 1999–2001. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/rushmore/peopleevents/p_gborglum.html.

South, Will, Marian Yoshiki-Kovinick, and Julia Armstrong-Totten. A Seed of Modernism: The Art Students League of Los Angeles, 1906–1953. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2008.

Traditional Fine Arts Organization. “A Brief Biography of William Merritt Chase, 1849–1916.” 2011. http://www.tfaoi.com/aa/1aa/1aa435.htm.