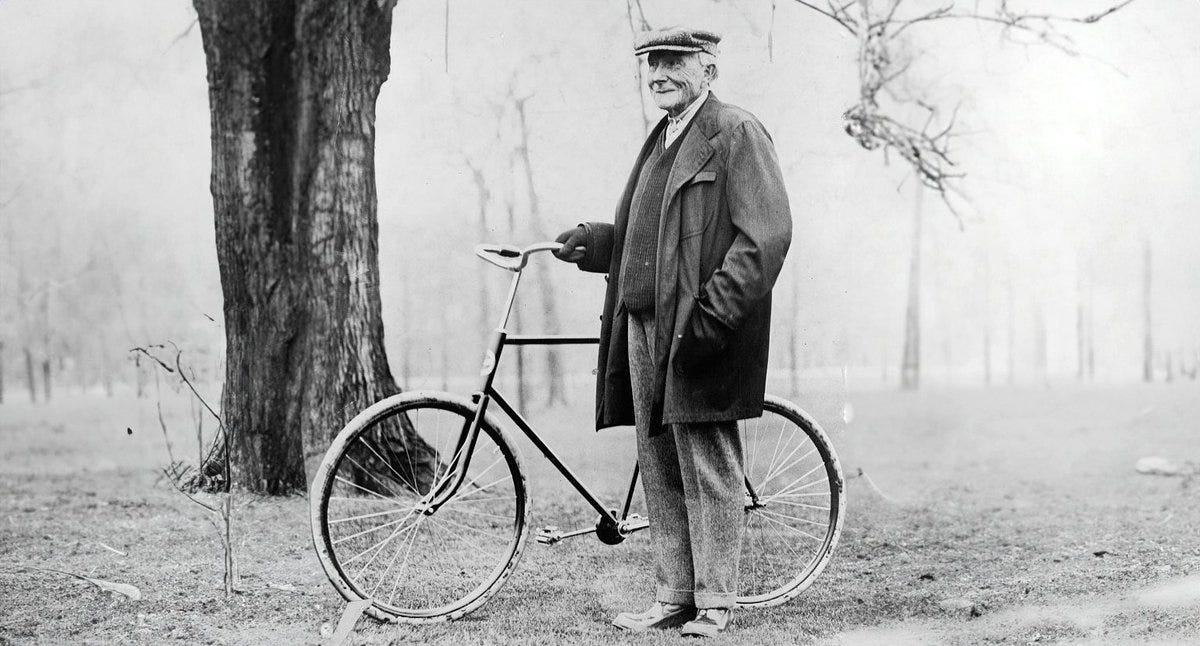

The story of John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil epitomizes the transformative and often ruthless spirit of American capitalism during the late 19th century. In the 1870s, the oil industry was ripe for domination, as the capital required to buy or build an oil refinery was relatively low, encouraging a flood of small-scale competitors.

Rockefeller, the largest refiner in Cleveland, systematically outmaneuvered his rivals through innovative strategies and aggressive tactics. He secured secret railroad rebates in exchange for his steady business, allowing him to transport oil at a lower cost than his competitors. This advantage enabled Rockefeller to undercut rival refiners, driving many out of business.

In 1882, Rockefeller and his associates introduced a groundbreaking corporate structure called the trust. The Standard Oil Trust allowed trustees to hold stock in multiple refinery companies “in trust,” enabling them to coordinate policies across the industry. Rockefeller consolidated his control through an elaborate stock swap, achieving a near-monopoly on oil refining. This model soon inspired the creation of trusts in other industries, cementing Standard Oil’s position as a corporate organization pioneer.

Public backlash against trusts grew as critics denounced them for stifling free trade and fostering unethical practices. In response to mounting pressure, the federal government outlawed trusts, prompting Rockefeller to adapt. Standard Oil reorganized as a holding company, centralizing control under a single administration. This move ensured that the various entities under Rockefeller’s influence acted in concert while appearing to be separate businesses. By 1890, Standard Oil controlled 90% of the U.S. oil market, and Rockefeller became a symbol of the era’s industrial titans.

“The Standard Oil Company, by 1899, was a holding company which controlled the stock of many other companies. The capital was $110 million, the profit was $45 million a year, and John D. Rockefeller's fortune was estimated at $200 million. Before long he would move into iron, copper, coal, shipping, and banking (Chase Manhattan Bank). Profits would be $81 million a year, and the Rockefeller fortune would total two billion dollars.” — Howard Zinn

Ida Tarbell’s Exposé

The rise of investigative journalism brought new scrutiny to Rockefeller’s empire. From 1902 to 1905, Ida Tarbell published a series of articles in McClure’s magazine exposing Standard Oil's unsavory tactics. Tarbell, whose father had been driven out of the oil business by Rockefeller’s aggressive practices, meticulously researched Standard Oil’s dominance.

Her work painted Rockefeller as the quintessential heartless monopolist and fueled public discontent with the concentration of corporate power. Tarbell’s exposés played a pivotal role in shaping public opinion and paved the way for government intervention against monopolies.

Rockefeller’s legacy remains complex. While he revolutionized the oil industry and laid the foundations for modern corporate structures, his methods highlighted the tensions between innovation and exploitation during the Gilded Age.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Corbett, P. Scott, Volker Janssen, John M. Lund, Todd Pfannestiel, Paul Vickery, and Sylvie Waskiewicz. U.S. History. Houston, TX: OpenStax, Rice University, 2014.

Locke, Joseph, and Ben Wright, eds. The American Yawp.

Schweikart, Larry, and Michael Allen. A Patriot's History of the United States: From Columbus's Great Discovery to the War on Terror. New York: Sentinel, 2004.

Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. New York: Harper & Row, 1980.