Origins of the American Indian

Most Native American origin stories claim an unbroken bond to the land, asserting that Native nations have always called the Americas home. But peel back the layers of time, and some scholars tell a different tale—one etched in ice and migration.

They argue that a vast land bridge stretched between Asia and North America between nine and fifteen thousand years ago, now lost beneath the waves, known as Beringia. Across this icy expanse, the first peoples of the Americas are believed to have wandered, driven by the primal pursuit of food. When the glaciers surrendered to the warming Earth, the seas rose, swallowing Beringia and leaving in its place the frigid waters of the Bering Strait.

But history rarely unfolds in straight lines. Recent research hints at another path: a watery corridor along the rugged west coast of South America. Evidence suggests that ancient mariners may have hugged the coastline, traveling by both land and sea. Genetic breadcrumbs—shared Y chromosome markers between Asians and Native Americans—add weight to this maritime migration theory. Later still, brave souls crossed the narrow strait by boat, pressing ever southward, scattering across the continents, and weaving the rich tapestry of cultures from the urban sprawl of civilization in the heart of Mexico to the woodland tribes nestled in the forests of eastern North America.

Around ten thousand years ago, another revolution quietly took root: the domestication of plants and animals. Once restless and transient, humanity began to anchor itself to the soil. With agriculture came abundance, and with abundance came permanence. People built not just homes but communities, etched into the landscape with permanence. Their lives were no longer dictated solely by the hunt but enriched by the harvest. The seeds they planted grew not just crops but civilizations.

The Gift of Corn

In the heart of the Sioux nation, where the vast plains meet the horizon, a tale as enduring as the land itself exists: the story of the Gift of Corn. This narrative, passed down through generations, speaks of an old hermit, a man who had retreated from the bustle of village life to seek solace in the embrace of the wilderness. He spent his days wandering the dense forests, gathering roots and herbs for sustenance and healing properties. His reputation as a healer was known, and occasionally, warriors would seek him out, traversing great distances to procure his renowned remedies.

One evening, after a particularly exhaustive day, the hermit returned to his humble abode, a tent fashioned from buffalo skins. As he lay upon his deerskin bed, teetering on the edge of slumber, he felt a gentle nudge against his feet. Startled, he opened his eyes to an astonishing sight: a radiant spirit beckoning him. This ethereal being invited the hermit to its dwelling. Intrigued and unafraid, he accepted the invitation.

The spirit led him to a magnificent field unlike any he had ever seen. The land was adorned with tall, golden stalks, swaying gracefully in the evening breeze. The spirit revealed that these stalks were a sacred gift, a nourishment source to sustain his people. The spirit taught the hermit the methods of cultivation, the rhythms of planting and harvesting, and the reverence required to honor this divine provision.

Upon awakening, the hermit was filled with a profound sense of purpose. He returned to his people, imparting the knowledge bestowed upon him by the spirit. The Sioux embraced this gift, and corn became central to their sustenance and culture. To this day, the story of the Gift of Corn is recounted, a testament to the deep connection between the Sioux, the land, and the benevolent forces that guide them.

Like many indigenous narratives, this tale underscores a profound truth: the gifts of the earth are sacred, and with them comes a responsibility to honor and cherish the natural world. The story of the Gift of Corn is not merely a legend but a guiding principle, reminding the Sioux of their blessings and their duty to preserve the harmony of their existence.

American Tale of Seeds and Civilization

Agriculture, that quiet revolution, crept into human history sometime between nine thousand and five thousand years ago, not with the thunder of conquest but with the whisper of sprouting seeds. It blossomed almost simultaneously on both sides of the world, weaving itself into the fabric of human existence. In Mesoamerica, amidst the rugged terrains of what we now call Mexico and Central America, maize—corn—became more than a crop; it became the cornerstone of civilization. Around 1200 BCE, domesticated maize nurtured the hemisphere's first settled populations. High in calories, easy to dry and store, and generous enough to yield two harvests a year on the Gulf Coast's warm, fertile soil, corn was both sustenance and symbol, its golden kernels cradling the promise of permanence.

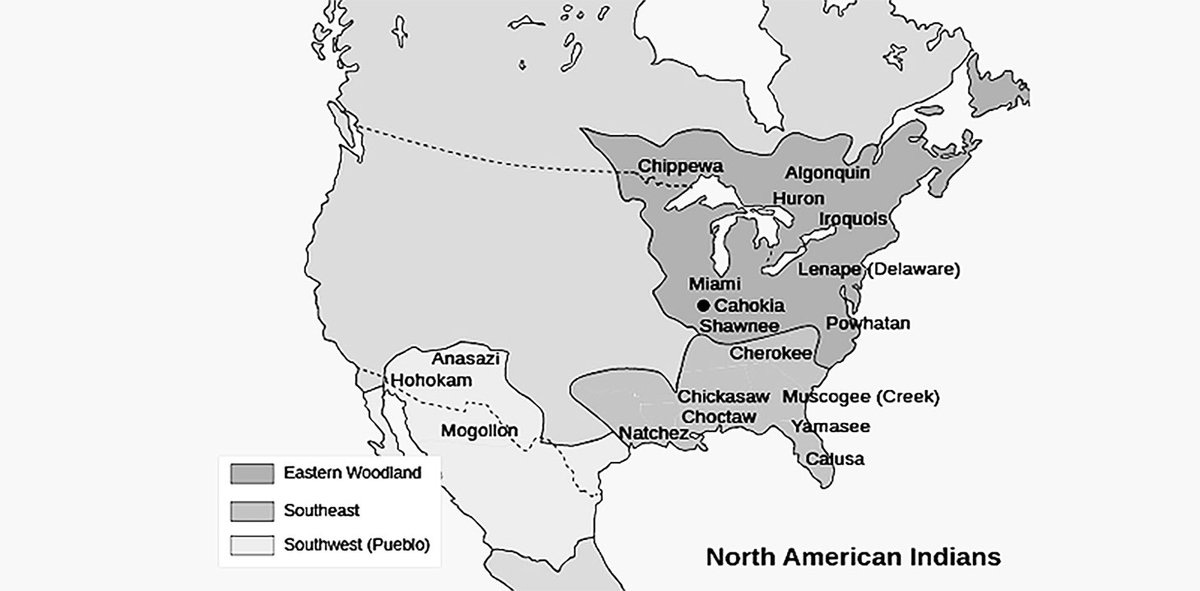

But corn did not stand alone. It traveled, its roots threading through the continent, intertwining with the cultural and spiritual lives of countless Native communities. In the Eastern Woodlands, cradled between the Mississippi River and the Atlantic Ocean, agriculture flourished with a trinity: corn, beans, and squash—the Three Sisters. Together, they were more than mere crops; they were companions, their growth a delicate dance of mutual support. Corn provided a sturdy stalk for the beans to climb, beans fixed nitrogen to enrich the soil, and squash sprawled along the ground, its broad leaves shading weeds and retaining moisture. This symbiotic trio sustained bodies, cities, and civilizations.

Native communities shaped the land with an artistry born of necessity and reverence. They managed forests with controlled burns from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic coast, transforming dense undergrowth into expansive, park-like hunting grounds. They planted the Three Sisters where the ash fell, embedding food like a living mosaic into the landscape. Shifting cultivation was a common practice: fields cleared, crops sown in the nutrient-rich ashes, and when the land grew weary, left to rest, the forest reclaiming its dominion until the cycle began anew. This rhythm of renewal thrived in soils that challenged permanence.

Yet, in the fertile embrace of the Eastern Woodlands, Native farmers laid down deeper roots. Here, the land's richness allowed for permanent, intensive agriculture. Armed with simple hand tools, they cultivated the earth with care that balanced productivity and sustainability, drawing bountiful harvests without depleting the soil. Women, the stewards of these gardens, shaped the agricultural heartbeat of their communities, while men hunted and fished. Their roles intertwined like those of the Three Sisters themselves.

Agriculture did more than feed bodies; it redefined societies. With surplus came specialization. Freed from the daily quest for food, some turned to other callings: religious leaders wove spiritual tapestries, soldiers honed their prowess, and artists etched beauty into stone and song. But this bounty bore its own burdens. The archaeological record whispers of bodies less robust and teeth more fragile as diets shifted from diverse foraging to reliance on cultivated staples. Even so, the seeds of agriculture yielded more than crops—they sprouted cities, ceremonies, and civilizations, a testament to humanity's enduring relationship with the land.

Cahokia: Metropolis Before America

In the shadow of the Mississippi River, where the American Bottom's floodplain stretches vast and fertile, there once rose a city unlike any other in pre-Columbian North America: Cahokia. Its story is both an enigma and an epic, stitched together from mounds of earth, fragments of pottery, and the spectral echoes of lives long vanished. If history is a tapestry, Cahokia’s threads are woven with ambition, power, and collapse.

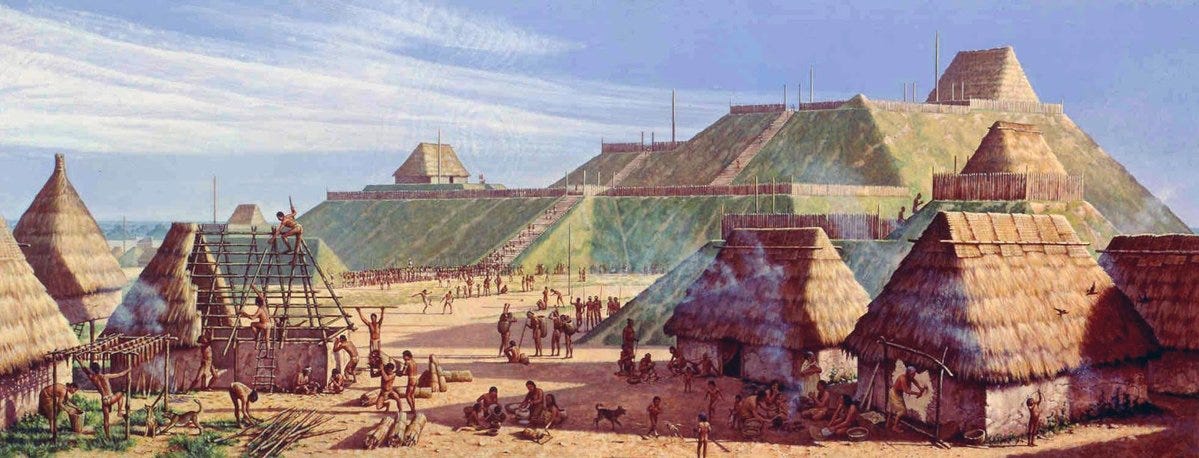

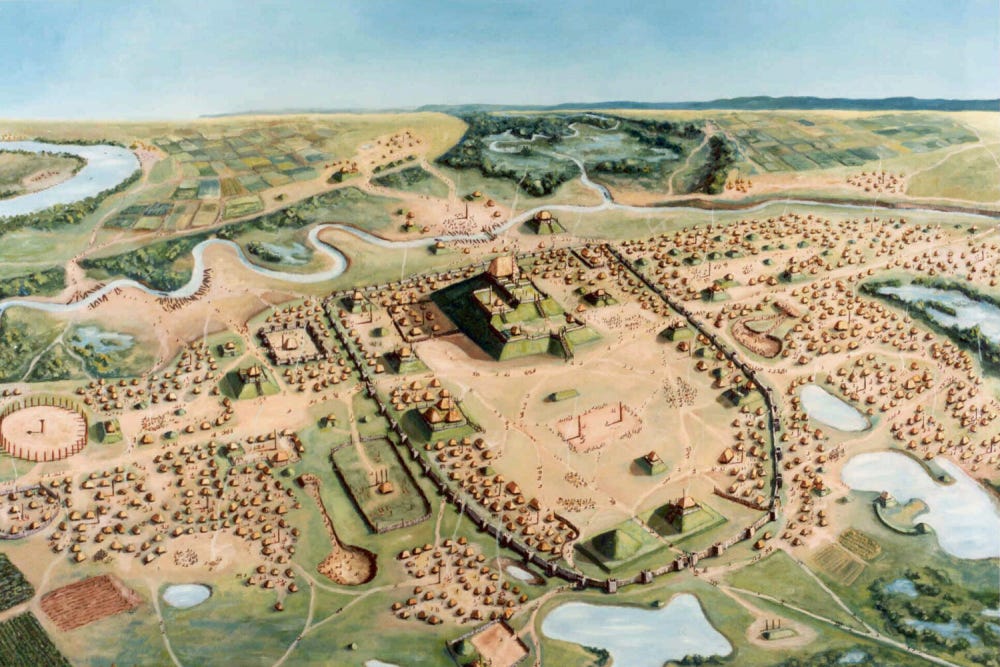

Around 1050 A.D., a transformation occurred so swiftly and profoundly that archaeologist Timothy Pauketat called it the “Big Bang” of Cahokian society. A modest settlement erupted into a sprawling metropolis covering 14 square kilometers, its skyline punctuated by over 120 earthen mounds. At the heart of this city stood Monks Mound, a gargantuan structure measuring 291 by 236 meters at its base and rising 30 meters high, containing over 615,000 cubic meters of earth. It dwarfed all other structures north of Mesoamerica, save for the pyramids of Cholula and Teotihuacán.

Cahokia was meticulously planned. Its Grand Plaza spans 19 hectares and is flanked by mounds and ringed by a palisade of 20,000 logs. This wasn’t just a city; it was a statement. The alignment of mounds and plazas suggests a cosmological blueprint where urban design meets spiritual order.

At its zenith, Cahokia’s population swelled to between 10,200 and 15,300—an unprecedented figure for North America north of Mexico. This boom was fueled by migration from surrounding upland villages, whose inhabitants were drawn into the city’s orbit, transforming from rural farmers to laborers on monumental construction projects.

Cahokia’s elites wielded immense power, both sacred and secular. Mound 72 bears a grisly testament: it contained the remains of 53 young women, likely sacrifices, their lives extinguished to underscore elite dominance. The city’s political structure fused theocratic rule with social stratification, supported by an economy rooted in intensive agriculture, mainly maize, supplemented by a diverse array of native plants and animals.

Cahokia thrived on its environment's metabolic energy. The fertile floodplains, enriched by periodic inundations, supported large-scale maize agriculture, while upland villages like the Richland Complex supplied additional food. Yet, this prosperity came with costs. Intensive land use led to deforestation and soil depletion, exacerbated by the city’s insatiable demand for timber for construction and fuel.

By 1200 A.D., signs of stress surfaced. The city’s population declined by nearly 50% during the Stirling Phase (1100–1200 A.D.) and even more precipitously in the Moorehead Phase (1200–1275 A.D.). The reasons are manifold: environmental degradation, climate shifts marked by flooding and drought, and the social strain of supporting an increasingly complex hierarchical society.

Public works persisted even as the population dwindled, suggesting that elite demands may have hastened the collapse. The palisade was rebuilt multiple times, possibly reflecting internal conflict or external threats. By the Sand Prairie Phase (1275–1350 A.D.), Cahokia was a shadow of its former self, its mounds silent, its plazas empty.

When Europeans arrived centuries later, they found only enigmatic mounds and scattered remnants. Cahokia’s story, like that of Rome or the Maya, speaks to the universal arc of civilizations: rise, flourish, decline. Yet, it also challenges us to reconsider what we think we know about urbanization, complexity, and the fragility of human societies. In the heartland of America, Cahokia stands—or rather, slumbers—as a testament to what was and what might yet be.

Eastern Woodland

East of Cahokia, where forests unfurl in endless green and rivers carve veins through the land. Native peoples lived not under towering mounds or within sprawling metropolises but in smaller, self-reliant communities stitched together by kinship and tradition. These were not monolithic societies but patchworks of autonomous clans and tribes. Each adapted to the rhythms of its environment. Warfare was part of life, driven by the desire to protect hunting grounds and fishing waters, yet these tribes shared a common thread: leadership that was less about dominion and more about council. Chiefs, often men, led with the guidance of women who selected and advised them, their influence woven deep into the social fabric—a contrast to the rigid patriarchies of Europe, Mesoamerica, and South America.

In the Eastern Woodlands, where rivers like the Hudson and Delaware wove lifelines through the land, the Lenape (or Delawares) cultivated the fertile bottomlands. Their settlements, scattered from southern Massachusetts to Delaware, were loosely connected not by centralized power but by shared stories, ceremonial practices, and kinship networks. They lived within a tapestry of oral histories, matrilineal clans, and consensus-driven councils, where a man joined his wife’s clan upon marriage, and women tended the fields of corn, beans, and squash—the Three Sisters—while men hunted, fished, and safeguarded their communities.

The resilience of Lenape societies stemmed from their intimate knowledge of the land. Women, the architects of agriculture, planted tobacco, sunflowers, and gourds alongside the staple crops, harvesting fruits and medicinal plants with practiced precision. Their communities moved with the seasons, gathering in larger groups during planting and harvest, dispersing again to follow the migrations of animals and birds. They established seasonal fish camps along rivers and coasts, weaving nets from rushes and drawing sustenance from the water's bounty.

When Dutch and Swedish settlers arrived in the seventeenth century, they found not wilderness but a civilization rooted in prosperity and ecological harmony. The Lenape’s diplomacy was as vital as their agricultural acumen, for the newcomers quickly realized that their survival depended on Lenape friendship and knowledge.

In these societies, raising children was a shared endeavor, with both men and women playing crucial roles. Matriarchal structures, like those of the Iroquois, Muscogee, and Cherokee, granted women authority over marriages, households, and even the selection of leaders, known as sachems. Leadership was earned through wisdom and experience, not inherited titles and sachems governed by the consent of their people. Unlike the hierarchical Mississippian cultures, the Lenape’s dispersed authority fostered stability, resilience, and a deep sense of community.

Large councils convened for ceremonial gatherings or significant decisions, where the voices of men, women, and elders mingled in shared governance. Though tensions with neighboring groups like the Iroquois or Susquehannock occasionally flared, the absence of defensive fortifications around Lenape settlements speaks to a society that prized negotiation over conflict and community over conquest.

Spiritual Beliefs

For the Indigenous peoples of North America, the boundary between the natural and the supernatural was as fluid as a river's current. Spiritual power was not distant or abstract but woven into the very fabric of their world—present in the rustle of leaves, the flight of a bird, and the breath of the wind. It was accessible and tangible and could be invoked through rituals, songs, and ceremonies.

Kinship was the bedrock of these societies, threading through matrilineal lines where family identity flowed from mothers to daughters. In many cultures, fathers joined their wives' families, and uncles often played pivotal roles in raising children, reinforcing women's central influence in both domestic and political spheres. Here, power did not flow solely from male lineage but was shared, with men’s identities often anchored in their relationships with women.

Cultural norms around marriage and sexuality reflected this fluidity. Women often chose their partners, and divorce was straightforward, unburdened by the rigid legalities that European settlers would later impose. Property, too, was viewed differently. While personal items like tools or weapons were individually owned, land was a collective resource. The right to use land was sacred, but ownership in the European sense—as something to be bought, sold, and possessed perpetually—was foreign. Instead, land was a living entity, and its use was negotiated through community consensus and respected boundaries.

In these ways, Indigenous spiritual beliefs and social structures revealed a profound connection to the land and one another. In this worldview, everything was interwoven: people, nature, and the spirit world, each thread vital to the integrity of the whole.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

OpenStax. U.S. History. Houston: OpenStax, 2018. https://openstax.org/details/books/us-history.

Tainter, Joseph A. “Cahokia: Urbanization, Metabolism, and Collapse.” Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 1, no. 6 (2019): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2019.00006.

“Sioux Story of the Gift of Corn.” World History Encyclopedia. Accessed February 1, 2025. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2282/sioux-story-of-the-gift-of-corn/.

Wright, Joseph L., and Locke, Benjamin. The American Yawp. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. https://www.americanyawp.com