What is Graft?

"Back of all this Ruef question is the fundamental question, 'What is graft?' When a Catholic gives a dollar to a priest to have a Mass said for him the Protestant shouts 'graft.' When a Protestant gives his minister a fee for funeral services the atheist shouts 'graft.' When Heney gets $42,000 from a corporation for 42 hours' work, all his enemies shout 'graft.' When Ruef gets $100,000 from another corporation also for work the whole town yells 'graft.' But the still, small voice still asks the question, 'What is graft?'" — Father Peter C. Yorke, The Leader, April 11, 1908

The Roots of Two City Bosses

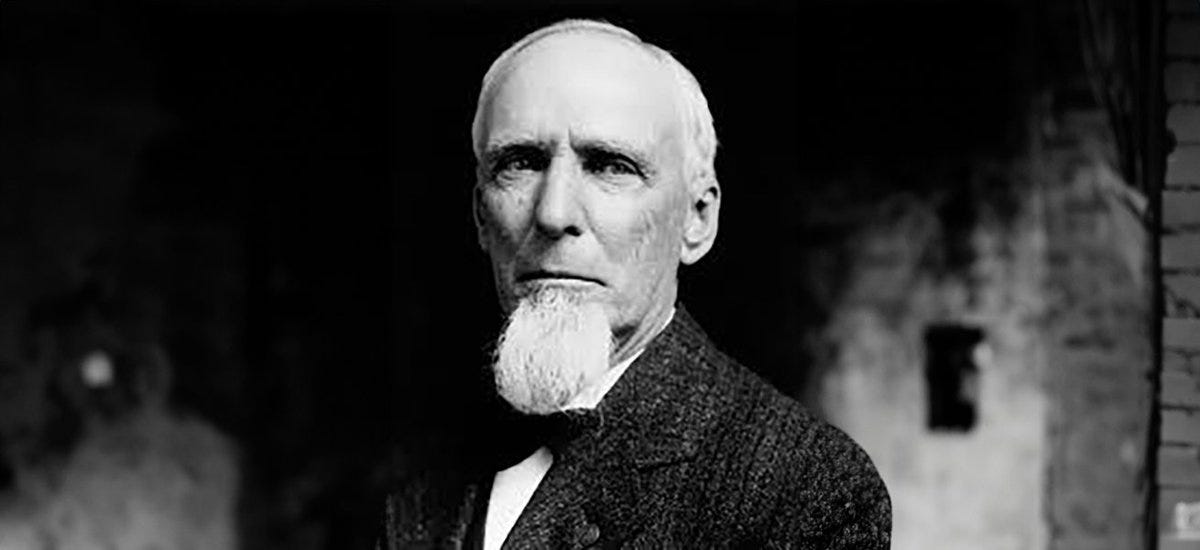

Abraham Ruef (originally spelled Rueff, he dropped an 'f' to sound less Jewish) was born in 1864 to Alsatian Jewish immigrants. A brilliant young man, Ruef graduated from the University of California with high honors at eighteen and then from law school three years later. He was no product of the immigrant slums, nor was he so hungry for a loaf of bread that he climbed into politics for his supper. Instead, he hungered for influence, shaped not by taverns and precinct cliques but by classical studies and legal training. For all that learning, though, he discovered the same lure that had snared other big-city politicians: the chance to orchestrate men’s destinies from a backroom’s shadows.

In Los Angeles, Meyer Lissner likewise carried the air of an outsider. A child of German-Jewish parents, he was not molded by the ward clubs that forged many East Coast Irish bosses. Instead, Lissner came West as a bold entrepreneur, stepping into watchmaking, law, and real estate with equal tenacity. His gift for organization soon swept him into city politics, where he aimed to reform local government by modernizing elections and trimming away the corruption he believed was suffocating Los Angeles.

If Ruef was drawn into city politicking with one foot in the old traditions of franchising deals, Lissner marched in proclaiming a new gospel of efficiency. Yet both men found themselves labeled “boss,” each grappling with the same question: how to bend a city’s tangled politics to do their bidding.

Corruption and Its Strange Fruits

Folks often imagine corruption like black mold on a peach, wholly rotten and best tossed away. But in San Francisco and Los Angeles, the city’s fortunes were sometimes shaped and improved by the men who greased palms and bankrolled campaigns. Under Ruef, the Union Labor Party took hold of San Francisco’s government and, for a short while, gave workingmen a sense of political power they’d never had before.

Once the party’s new supervisors were installed, the city swiftly passed ordinances to help rebuild after the great earthquake and fire in 1906, clearing rubble and arranging rebuilding efforts at breakneck speed. This burst of labor-backed authority might not have come without Ruef’s canny orchestration—and, yes, the bribes he paid to ensure votes went the way he and his corporate allies wanted.

In that sense, corruption didn’t always appear as senseless looting. Sometimes, it greased a squeaking machine, finished business, and allowed men and their families to eat and sleep. But the same graft that sped things along also soured the city’s spirit. Those naive labor supervisors Ruef had chosen soon realized they could be “rented” by anyone with deep pockets. If it wasn’t Ruef’s share of utility money, it might be cash from rival telephone companies or streetcar magnates. With no strong machine discipline, the supervisors scurried about, freewheeling in bribery.

The old giant of California—the Southern Pacific Railroad—continued its usual maneuvers in the background, and every day voters watched the spectacle with growing disgust. Eventually, the famed Graft Prosecution swept in, toppling Ruef, sending him to San Quentin, and exposing all the free-lance bribery in the city’s board of supervisors.

In Los Angeles, Lissner’s brand of “bossism” was different. If Ruef tried to amass power by parlaying corporate fees into political influence, Lissner believed in forging a broad consensus with his direct primary law and nonpartisan reform. He never paid off local councilmen or stuffed ballots; instead, he organized a city’s worth of do-gooders and business progressives into the Good Government Organization (GGO).

Yet critics sneered that the GGO was just another machine, with Lissner pulling the strings out of his law office. In truth, there was a system to it—a network of clubs, newspapers, and committees all singing the tune of efficiency and honesty. So while Ruef’s corruption was more brazen, Lissner’s “machine” was gentler, built upon the trust of wealthy publishers, reform clubs, and an electorate weary of old party politics. That brand of paternalistic control could ironically yield as much influence over municipal decisions, from new charters to the appointment of utility commissioners.

PART I: THE RISE OF ABE RUEF, THE PRIDE AND PREJUDICES OF JAMES PHELAN, AND THE REBIRTH OF SAN FRANCISCO

San Francisco at the Turn of the Century

The year is 1900. From the wind-swept ferry terminals along the Embarcadero to the lively burlesques of the Barbary Coast, San Francisco teems with noise, commerce, and ambition. Cable cars clatter up Nob Hill; bankers and newsboys brush shoulders on bustling Market Street. Tucked into a modest law office is Abraham Ruef, a brilliant but unassuming attorney who senses that the old Republican guard may be vulnerable.

Meanwhile, Mayor James D. Phelan reviews his latest City Hall plans across town in a grand, column-fronted building. A patrician by birth, he is the preeminent champion of an ambitious “City Beautiful” crusade—one that promises wide boulevards, stately public buildings, and elegant parks reminiscent of the world’s grandest capitals. Under Phelan's guidance, funds are steered toward an expanded civic center, new library branches, and statuary in public squares. He dreams of a city that glitters as brightly as Paris, believing this “City Beautiful” approach will elevate the populace.

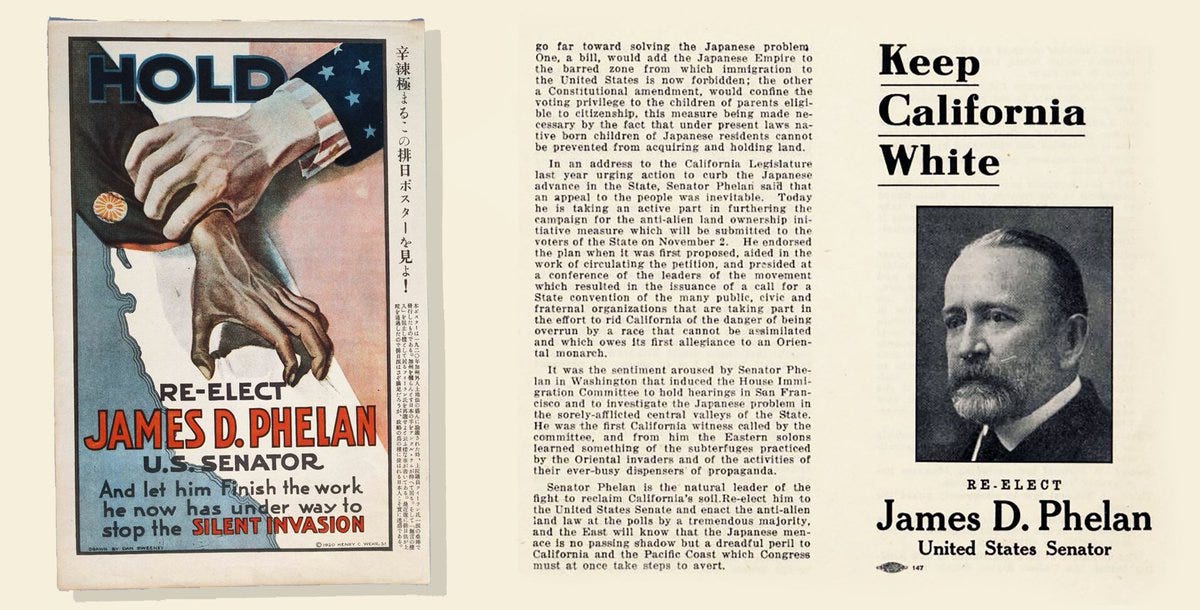

Yet, in private, Phelan’s admirers overlook—or willfully ignore—another facet of his politics: a sharp and vocal hostility to immigration, mainly Chinese. Though he styles himself a reformer, championing philanthropic causes and cultural improvements, he simultaneously agitates for restrictions to keep “undesirables” away from San Francisco’s core. This paradox—magnificent civic artistry on the one hand, bitterly prejudicial rhetoric on the other—places Phelan squarely at the center of a complex era.

Phelan Ascends, Ruef Lies in Wait

In his youth, Phelan rose to the mayoralty on a promise to stabilize a city long tested by labor unrest. By the late 1890s, he had secured the endorsement of business leaders who admired his blend of paternalistic leadership and progressive city planning. He poured municipal attention into grand boulevards, calling in acclaimed architects to craft a future civic center that might dazzle visitors and residents alike.

Not content with shaping the city’s roads and buildings alone, he funded libraries and sponsored various cultural projects. Portraits of him in local papers emphasized his earnest gaze and moral tone, implying he alone could deliver a “clean, beautiful city” worthy of the moniker as the West’s grandest port.

But the times were shifting. A labor movement was stirring in hidden corners of union halls, where people were resentful of Phelan’s alignment with commercial interests. Enter Abraham Ruef, the astute political operator. Raised by French-Jewish parents and armed with a top-tier education, Ruef had once attempted to control the local Republican machine, and eventually, Ruef's ambitions outgrew the Republican structure.

By 1901, frustrated with his inability to dominate the local Republican organization, he broke away and shifted his focus to the newly formed Union Labor Party. There was no room in the Democratic party, as Ruef would only be rebuffed by Phelan’s circle of confidants. Undeterred, he recognized an opportunity in a nascent Union Labor Party. Spotting a charismatic figure—Eugene Schmitz, a theater orchestra conductor with dramatic flair—Ruef carefully fashioned a three-way contest in 1901.

On election night, San Francisco reeled from the outcome: Schmitz, the labor candidate, defeated Phelan in a surprise upset. Overnight, the mayor’s gilded speeches about “civic refinement” were overshadowed by rueful headlines: “City Hands Keys to Labor.” Stung, Phelan retreated from City Hall but refused to vanish.

Gilded Corruption and Phelan on the Sidelines

For the next four years, Schmitz’s mayoral office became a stage where Ruef performed discreet puppeteering. While Schmitz, the handsome mayor, appeared at labor picnics, Ruef angled for corporate fees, meeting public utility barons who paid handsomely to protect streetcar franchises or telephone monopolies. The old Board of Supervisors, hapless and easily swayed, found itself quietly receiving “fees” through Ruef, who parceled out thousands of dollars under the table.

Across town, Phelan—once again a private citizen—turned increasingly to philanthropic efforts. He financed community centers, pressed for more cultural institutions, and emphasized an even grander notion of “City Beautiful.” He was known to sponsor local artists and award scholarships to the gifted. Yet, in the back rooms of exclusive clubs, Phelan railed about keeping California for white men. Newspapers printed praise for his philanthropic generosity and little condemnation of his nativist outbursts.

Meanwhile, Schmitz and Ruef felt flush with influence. Even moderate voices who once doubted labor found themselves uneasy at the scale of bribes that seemed to swirl around City Hall. At quiet dinners in Nob Hill mansions, warning spread of Ruef that he was a man of fleeting loyalties and seemingly bottomless personal greed.

The Earth Shakes, Fires Rage

Dawn of April 18, 1906. A violent tremor rips through San Francisco, toppling buildings in an instant. Gas lines burst, fires erupt, and chaos ensues. Within days, the city lies half in ruins. Mayor Schmitz tries to coordinate relief, Ruef rushes to broker emergency deals with outside suppliers, and James Phelan plunges into relief operations.

Phelan dashes off telegrams to wealthy contacts, raising funds for bread lines and tent cities. As president of the San Francisco Relief and Red Cross Funds, Phelan proved instrumental in coordinating and raising funds to support the devastated city. His efforts included securing substantial financial aid, such as the $10 million personally sent by President Theodore Roosevelt for relief, which Phelan helped administer. But the quake and fire were not a total disaster in Phelan's eyes. He envisioned this as a chance to rebuild and implement his City Beautiful dream on a scale no one could have anticipated.

But heartbreak overshadows these grand plans. Thousands are homeless. Troops patrol the smoky streets, and rumor blames labor agitators for looting. Phelan stands amidst the rubble, lamenting the city’s misfortune, determined to see it reborn. When a local committee forms to direct reconstruction efforts, Phelan joins it at once, pushing for wide boulevards, grand neoclassical buildings, and a modern civic center. In that moment of communal crisis, he sets aside—if only briefly—his antagonisms, working alongside men of every background.

Yet in the weeks that follow, Phelan reverts to form. Urging reconstruction guidelines that restrict the city’s Chinese residents to a cramped quarter, he revives the old xenophobic refrain. Some relief volunteers balk, outraged that he’s using the quake to push racial segregation. Meanwhile, Ruef and Schmitz entrench themselves in new controversies, as allegations swirl that they’re funneling relief contracts to cronies.

Graft Exposed and Judgment Falls

Months after the ashes cool, the city seethes with rumors of corruption. Behind closed doors, Rudolph Spreckels, a young sugar heir, secretly funds an investigative campaign, hiring Francis J. Heney, a tough-minded special prosecutor. Working with District Attorney William Langdon, Heney peels back the layers of bribes to city supervisors. He soon has a star witness: a jittery supervisor confesses to receiving thousands from Ruef’s lawyer fees, courtesy of corporate bigwigs.

The San Francisco Graft Prosecution

In the annals of San Francisco’s turbulent history, few episodes rival the graft prosecution that erupted in the wake of the 1906 earthquake—a calamity that shook the earth and the city’s tolerance for the corruption festering within its foundations. The need to rebuild, to rise anew from the ashes, became the catalyst for plans long simmering before the quake struck. Those plans, championed by a resolute few, now intensified with an urgency that could no longer be ignored, setting in motion a crusade to purge the city of its entrenched malfeasance.

At the heart of this endeavor stood Fremont Older, editor of the San Francisco Bulletin, a man of ink and conviction whose pen had long decried the city’s moral decay. The scheme's originator was a bold design to root out corruption, initiated by Older and with the cooperation of District Attorney William Langdon. Together, they resolved to hire special detectives—men untainted by the city’s soiled politics—to unearth the evidence that would topple the mighty. To fund this audacious undertaking, Older secured the pledge of Rudolph Spreckels, a reform-minded millionaire capitalist whose $250,000 infusion into the prosecution fund signaled that the battle was joined in earnest.

The Spreckels name was no stranger to San Francisco’s tumultuous saga. Rudolph and his brother Adolph, sons of the sugar baron Claus Spreckels, bore a legacy as complex as the city itself. Adolph, the elder son, had once let rage seize him when the Chronicle accused his family’s sugar empire of defrauding shareholders. In 1884, leaning from a taxi, he fired upon Michael de Young, the newspaper’s publisher, in front of its building. A jury, swayed by a plea of “temporary insanity,” acquitted him—a verdict that whispered of San Francisco juries’ disdain for the de Young clan. The Spreckels were no saints, but Rudolph’s commitment to reform lent a sheen of redemption to their tarnished crest.

Older’s vision required more than local resolve; it demanded federal muscle. He turned to President Theodore Roosevelt, a titan of righteous vigor, persuading him to lend the services of William J. Burns, the Secret Service’s star detective. With his keen eye and unyielding pursuit, Burns descended upon San Francisco like a hound on the scent. Alongside him came Francis J. Heney, the appointed assistant district attorney whose prosecutorial zeal would soon become legend. Older stood steadfast behind District Attorney Langdon, a bulwark against the political machine that had gripped the city since the turn of the century.

That machine, orchestrated by Ruef, held sway over San Francisco in 1906 with a grip as tight as iron. The Board of Supervisors, the Chief of Police, and several judges danced to Ruef’s tune, their loyalty secured by patronage and payoffs. Yet Ruef’s dominion faltered with one fatal misstep: William Langdon, the district attorney he had underestimated. Elected in 1905, Langdon refused to march to Ruef’s orders, instead wielding his office like a blade against the city’s vice-ridden underbelly. Brothels, dance halls, gambling dens, and hollow storefronts felt his wrath as he built a coalition of allies determined to reclaim San Francisco from its “anything goes” abyss.

Ruef’s wealth flowed from darker streams. He had extorted the so-called “French Restaurants”—establishments cloaked in respectability on their first floors with fine dining at modest prices, only to unveil private supper rooms on the second and brothels above. With the threat of yanking their liquor licenses, Ruef bled these dens dry, amassing a fortune that fueled his dominion. But the ground was shifting beneath him, and the reformers he had once counted as kin were gazing at him with cold intent.

Amid this storm, another thread of San Francisco’s discontent unraveled: the specter of Japanese exclusion. On February 23, 1905, the San Francisco Chronicle unleashed a torrent of inflammatory articles, painting the Japanese as harbingers of crime, poverty, and ruin—spies in the shadows, threats to American womanhood. The state legislature, with near-unanimous fervor, urged Congress to bar Oriental (Asian) immigrants, while the Japanese and Korean Exclusion League swelled to 80,000 strong.

Eugene Schmitz, elected mayor on the Union Labor Party’s anti-Oriental platform, rode this wave of fear. By May 6, 1905, the San Francisco School Board signaled its intent to segregate Oriental students, a plan left dormant until October 11, 1906—the eve of Schmitz and Ruef’s indictment—when it abruptly ordered 95 Japanese students, a mere fraction of the city’s 20,000 pupils, into a Chinatown ghetto.

The timing bore the mark of cunning, a distraction from the noose tightening around Schmitz’s neck. Across the Pacific, Japan’s government recoiled in protest, and President Theodore Roosevelt, ever the arbiter of national honor, dispatched U.H. Metcalf, his Secretary of Commerce and Labor, to plumb the depths of this affront. Metcalf’s report thundered back, branding the school board’s decree “a wicked absurdity,” a phrase that echoed through the halls of power.

Schmitz, seizing the uproar as a lifeline, mounted the stump with fiery defiance. He railed against federal meddling and swore his indictment sprang from his anti-Asain fervor—a claim as bold as it was hollow. Roosevelt summoned the school board to Washington, and unbidden, Schmitz trailed along, an insolent guest in the capital's corridors.

The President brokered a tenuous peace there, pressing the board to hush its actions while striking a pact with Japan to stem its emigrants’ flow—an executive order sealing the gates to Asian arrivals. Yet the specter of this clash lingered, stretching its tendrils into Calvin Coolidge’s day, when in 1924 a federal immigration bill etched the Japanese exclusion into the nation’s ledger, a bitter coda to a saga born in San Francisco’s restless streets.

In San Francisco, the graft prosecution gathered force like an avalanche of reckoning. Inspired by Lincoln Steffens’ notion that business leaders bore the guilt for bribes, not the politicians who pocketed them, Francis Heney offered amnesty to supervisors who confessed. Their testimonies piled high, an overwhelming mass of evidence that ensnared Ruef himself in a full confession. This led to an attempted assassination on Heney, who narrowly escaped with his life during the San Francisco graft prosecution. The incident occurred on November 13, 1908, leaving Hiram Johnson to take his place.

In the main trial, Hiram Johnson stepped into Heney’s shoes as special prosecutor, securing Ruef’s conviction in December 1908. This triumph propelled Johnson to the governorship in 1910 as a Progressive Republican. In turn, Ruef named Patrick Calhoun of United Railroads, Tirey L. Ford, and executives of gas and telephone empires who fell under his accusations.

Schmitz, too, faced justice, convicted of extortion in a French Restaurant case in 1907, though higher courts later voided the verdict. Ruef alone bore the weight of conviction, sentenced to 14 years in San Quentin, serving five as the scapegoat of a rotten system. Whispers of anti-Semitism shadowed his prosecution, a stain Fremont Older sought to erase by advocating for Ruef’s pardon and commissioning his memoirs for The Bulletin. On February 29, 1936, Ruef slipped from life, penniless and half-forgotten, his small acts of good eclipsed by the infamy that defined him.

Phelan's Rebirth and a Senator’s Ambitions

During the next half-dozen years, San Francisco leaders—led by progressive reformers and civic committees—labored mightily to resurrect their beloved metropolis. New steel-framed towers rise downtown, a bold new City Hall soars, and Phelan remains instrumental in securing funds for public improvements. Afoot is his proudest dream: to host an international exposition celebrating the completion of the Panama Canal (the Panama Pacific International Exposition), a testament to San Francisco’s resilience after quake and fire.

In 1914 and early 1915, the final pavilions and grand palaces of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition stood ready in the Marina District. World travelers arrive to marvel at the jewel-studded towers and lagoon-laced fairgrounds. James D. Phelan, now in the national spotlight, uses this success to catapult himself into higher office. Despite the city’s woes, he cites his proven leadership and announces a run for the U.S. Senate.

For a spell, the public is entranced by the exposition’s carnival lights, unaware of the darker side of Phelan’s worldview. As the fair draws to a close, newspapers report the senator-elect’s triumphant victory. Phelan heads to Washington, a Democrat, proclaiming he’ll guard California’s interests with the same zeal he showed in rebuilding San Francisco. Yet behind his senatorial statements—urging national infrastructure, protective tariffs, and continued philanthropic forays—lurks the old bitterness about immigration, especially from Asia. His campaign slogan, shouted in certain Democratic circles, is “Keep California White," a sentiment he openly shared.

San Francisco—its buildings now standing prouder than before, its governance reclaimed by reformers—seems at last to have buried the memory of “Boss Ruef” in an old jail. And James D. Phelan, with all his philanthropic zeal and disquieting racial beliefs, finds himself an emblem of a city’s complicated soul.

In the end, Abraham Ruef stood alone as the scandal’s sole convict, sentenced to 14 years and confined within San Quentin’s stern embrace, serving five as the scapegoat of a city's corrupted soul—some murmuring that anti-Semitism had unjustly fixed the spotlight upon him. Fremont Older, once his fierce adversary, sought his pardon and paid him to recount his political odyssey for The Bulletin, a final testament to a life of shadow and light. On February 29, 1936, Ruef departed this earth, penniless and half-forgotten, his small deeds of good lost amid the echoes of his ruin, a quiet close to San Francisco’s tempestuous chapter.

PART II: MEYER LISSNER AND THE GOOD GOVERNMENT CRUSADE

A Different Corner of California

South of the Golden Gate, where Abe Ruef once reigned—and fell—a young entrepreneur named Meyer Lissner began to chart a very different course. In Los Angeles, across sprawling valleys and sun-drenched foothills, he found neither the Union Labor movement nor the chaotic swirl of quake and graft that consumed San Francisco.

Instead, a small circle of forward thinkers in the Angel City saw the potential for a new civic order built on nonpartisan ideas. Lissner, shrewd, energetic, and a lawyer by training, quietly set his sights on cleansing local politics of old-fashioned machine influence and patronage. If Ruef’s story were one of grasping power behind closed doors, Lissner’s story would be one of earnest, painstaking reform—though just as dramatic in its way.

Beginnings in the City of Promise

The year is 1906. Los Angeles spreads outward in a patchwork of dusty roads, orchards, and neighborhoods that scarcely resemble the dense metropolis to come. While San Francisco reels from earthquake and scandal across the state, Los Angeles’s most significant political story is the behind-the-scenes hold that local bosses—Walter Parker, Billy Dunn, and allies—wield over city council seats and departmental appointments. They collaborate with corporate interests—transit lines, water companies—and keep the city “open shop,” all while the electorate endures a weak city charter that fosters nepotism and confusion.

Into this void steps Meyer Lissner. In his mid-thirties, with dark hair and a brisk manner, he has traveled from San Francisco’s quieter enclaves to the southern city in search of business opportunity, first in watchmaking, then in the law. Before long, Lissner noticed how civic affairs stagnated under half-hidden alliances between local party men and business barons. He sees how an upstart group of reform-minded lawyers, journalists, and young officials might, if well organized, transform Los Angeles into a model municipality—a place run by skilled administrators rather than by the old coteries of ward politicians.

Quietly, Lissner holds luncheon discussions with attorneys and editors who desire open, direct primaries, preventing party bosses from handpicking candidates. He forms friendships with figures like Dr. John Haynes, a champion of the recall and other direct democracy measures, and local newspaper publishers who resent how the big daily—led by the conservative Los Angeles Times—dominates political endorsements. Step by step, this loose confederation crystallizes into a movement. Lissner emerges as its spine, proficient at drafting policy and coordinating precinct support. They name it: the Good Government Organization.

The Rise of the Good Government Organization

Starting in 1907, the Good Government Organization (GGO) spread its word in meeting halls and living rooms. Lissner’s experience in the law helps him craft legislative proposals: direct elections for local offices, open debate on budgets, and a limit to backroom caucuses. While others might cynically assume “machine politics” is inevitable in big cities, Lissner’s “nonpartisan governance” message resonates. Some brand him a dreamer; others call him a man of cunning. A few even whisper that Lissner, for all his talk of openness, is building a reformist “machine” of his own.

Yet the GGO gained real traction when the city’s Democratic mayor, Arthur C. Harper, faced misconduct allegations in 1908. Harper’s ties to local corporate interests proved too blatant, galvanizing a recall effort—the first in a major American city. Lissner became the recall’s principal organizer behind the scenes, forging alliances with respectable business owners, union moderates, and civic clubs. Volunteers circulated petitions, gathered signatures, and filled the newspapers with stories of Harper’s administration's misdeeds.

Appalled by the GGO’s momentum, Harper’s defenders portray Lissner as a meddling upstart. The Los Angeles Times runs editorials denouncing him as a “self-appointed messiah.” Still, enough citizens rallied behind the recall. Harper resigned days before the special vote rather than face inevitable defeat at the polls. Jubilant, Lissne,r and the GGO secure the election of Mayor George Alexander, a respectable candidate who pledges to adopt reforms once in office.

With that victory, newspapers across Southern California applaud Lissner’s organizational prowess. Even progressive voices up north, recovering from Ruef’s downfall, take note of Lissner’s success. The city seems, at last, to be rid of the old boss style that once tethered local government to private deals. For Lissner, the moment is heady; after years of careful planning, the GGO stands at the center of municipal affairs.

The Struggle to Reform Utilities

Success breeds new challenges. Once in office, Alexander convened a new Board of Public Utilities. At Lissner’s urging, the city rewrites certain charters to ensure open bidding for public franchises—particularly water and streetcar lines. Corporate figures accustomed to sweetheart agreements panic. Rumors spread that Lissner wanted to dominate the awarding of franchises through the new commission. Rival businessmen quietly approached city council members, wondering if Lissner was just another boss, controlling from behind the curtains.

The biggest clash erupts over local electric service and telephone franchises. A labyrinth of proposals arises, each claiming to offer cheaper rates or better expansions for the city. Lissner believes in awarding them based on transparent cost-benefit. However, councilmen heavily courted by well-funded lobbyists argue for quicker decisions. Tensions rise when Alexander, once an ally, begins to worry that Lissner’s influence might overshadow the mayor’s own. The two exchanged polite but strained words in closed-door sessions, each privately accusing the other of letting personal ambition taint the city’s best interests.

In the press, some anti-reform voices blast Lissner for building a “one-man government.” They point to how effectively he marshals supporters to attend every hearing and dissect every contract. Though well-intentioned, the Los Angeles Times editorializes that Lissner has turned into a “reform boss.” He counters by reaffirming the GGO’s mission: open government, fair competition, and no hidden deals. Yet he admits privately to colleagues that reform leadership demands a disciplined network—and that discipline can look suspiciously like boss power.

High Tides, Rifts, and the Limits of Reform

By 1911, Lissner stood at the apex of local politics. The GGO helped pass a direct primary law, a milestone that frees elections from party nominations. Observers hail Los Angeles as a national leader in the municipal reform movement. Congratulatory letters arrive from across California, including some from northern progressives who recall the bitterness of Ruef’s scandal. Lissner quietly acknowledges that his path—though anchored in earnest nonpartisanship—has ironically given him a kingmaker’s aura.

But fractures soon emerge. When the Board of Public Utilities tries to impose rate caps and new regulations, older city council allies balk at the economic blowback from powerful interests. Meanwhile, leftists —Socialists and labor union radicals—criticize Lissner for ignoring workers’ grievances in his zeal for a “clean” government. They claim his reforms are purely structural, leaving deeper economic injustices unaddressed. Lissner, in turn, sees labor as risking chaos that might scare off business growth.

A deeper rift surfaces between Lissner and Mayor Alexander over the extent of city oversight in utilities. Alexander, fearing that too much confrontation might hamper foreign investment, replaced key commissioners with more business-friendly appointees. Hurt and exasperated, Lissner resigns from the commission, publicly lamenting that the city’s best chance for honest progress was slipping away. Allies see this as a sign that the GGO’s unity has cracked. Detractors claimed Lissner’s departure proved he was unwilling to yield to any compromise.

Disillusioned, the once-indomitable Lissner briefly withdraws from the daily fray. The GGO continues to function on the ground, but it lacks its old fervor. By 1913, Los Angeles’s reforms remain a partial success—council members are chosen more democratically, some patronage is curbed, and new charters expand accountability. Yet many worry that the impetus for bigger changes—like public ownership of utilities—has stalled. Lissner’s retreat from direct involvement leaves the city’s progressive cause without its principal strategist.

A Quiet Legacy

In the following years, Los Angeles experienced an economic boom. Skyscrapers rise downtown, and farmland yields to tract housing. The city grows more confident, culminating in various expositions and expansions that point toward a future overshadowing older coastal rivals. Lissner remains active in law and business, consulted by friends and politicians for counsel on reform measures, but no longer at the head of a transformative political movement.

In the wake of these developments, some reflect that Lissner, for all his organizational brilliance, never galvanized broad popular fervor. He had championed direct democracy laws and fair franchises but tended to see social issues—like wages or labor unrest—as secondary to “clean governance.” The result, critics argue, is that the city’s daily injustices, especially for poorer Angelenos, persisted. Even so, Lissner’s structural achievements—open primaries, nonpartisan ballots, municipal experts—endured, shaping the city’s governance for decades.

From the vantage of 1915, as San Francisco basks in the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, Lissner briefly visits north to observe the spectacle. He sees a Bay City restored to splendor, overshadowing the memory of Ruef’s humiliating end. Returning home, he muses on his city’s swirl of affluence, sprawl, and the partial successes of good government. He senses that while the GGO’s moment of glory may be past, the core ideals—efficiency, professionalism, and accountability—are embedded in Los Angeles’s political DNA. In that sense, he, like Ruef, changed his city’s path, though with far fewer moral blemishes and a legacy of inclusive structures that would guide future generations.

One Last Reflection

So the two men—Ruef of the Bay, Lissner of the basin—left behind layered legacies. Their brand of “bossism” diverged in style and method. Where Ruef soared swiftly on the wave of a labor movement he only half understood, Lissner planted deeper seeds of structural change in municipal politics. One used corruption as a direct bribe to pass an ordinance or seat a man in office; the other pursued a coordinated network of reform clubs and laws that shaped City Hall from within. If, in the end, both men were called bosses, it was because both saw politics as the orchard of power—tended by their cunning, their farmland of alliances.

Yet, each orchard came with weeds. Ruef’s brand of corruption overreached, toppling him in a legendary graft prosecution. Lissner’s lofty aims for a nonpartisan utopia left some communities feeling like they’d lost the tangy flavor of old local democracy. Corruption, for all its rottenness, could grease the squeaky tracks of a frantic city. And so, paradoxically, it sometimes sets the city’s progress in motion. But it also sowed seeds of bitterness: if City Hall was for sale, who indeed spoke for the plain man on the street?

In time, California cities moved on from the likes of Ruef and Lissner. People fell under new illusions, found new heroes, and cursed new villains. But the old lessons still whisper across the decades: the city can be swayed by promises of honest government or by wily gifts of graft, and sometimes it is the same city official offering both. In these stories of Abraham Ruef and Meyer Lissner, we see not just the cities they shaped but the complicated hearts of men, each certain he was forging a better tomorrow—each leaving behind a swirl of triumph and regret in equal measure.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bean, Walton E. “Boss Ruef, the Union Labor Party, and the Graft Prosecution in San Francisco, 1901–1911.” Pacific Historical Review, vol. 17, no. 4 (November 1948): 443–455.

Rolle, Andrew F. California: A History. 8th ed. Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 2008.

Stevens, Mark H. “The Enigma of Meyer Lissner: Los Angeles’s Progressive Boss.” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, vol. 8, no. 1 (January 2009): 111–136.

Walsh, James P. “Abe Ruef Was No Boss: Machine Politics, Reform, and San Francisco.” California Historical Quarterly 51, no. 1 (Spring 1972): 3–16.