Historian to Historian

As a student, learning about California’s Native communities often felt like navigating a labyrinth—each turn revealing another layer of complexity tangled in the vastness of language, culture, and geography. California isn’t just big—it’s dense, woven with the lives of countless Indigenous nations. Their histories were obscured beneath Spanish-imposed names like Luiseño, Gabrielino, and other names, which flattened diverse identities into colonial categories. Studying the California Missions only added more layers to peel back, each one revealing not simplicity but more nuance.

The clearest path through this dense thicket I have ever found came from the work of Edward D. Castillo. His scholarship became a compass. I’ve taken his insights as the foundation of this article, reshaping them into a narrative meant to move—not march—through history, condensed to fit the cadence and constraints of my classroom without losing the rhythm of the past. With my deepest respect to Edward D. Castillo — a historian I would not be a historian without — thank you for your inspiring career of fascinating and pioneering research.

I have also incorporated aspects from James J. Rawls and his predecessor, Walton Bean’s book, California: An Interpretive History. As a Community College student, this was a book my professor, Brian Waddington, at Citrus College, assigned. It is a wonderful book, a seed that sprouted a career, a staple throughout my academic career, and one I used early on as a professor. I must also drop the names of Lisbeth Haas and Andrew Rolle for California historians of the millennial generation, both staples in college classrooms everywhere, and their influence will forever be scattered upon mine.

Finally, as an advocate of OER (Open Educational Resources), I have incorporated the work of Robert W. Cherny, Gretchen Lemke-Santangelo, and Richard Griswold del Castillo by opening their work, Competing Visions: A History of California, to the open-source community. Their work will become the foundation for the work of Generation Z. After releasing their work into the open for those who, like me, were trained as historians more by the books and media they encountered than in the classroom, where admission was required. A younger version of myself would have found this invaluable, so I will use this opportunity to introduce your work to as many eager minds searching for knowledge without a fee, exclusivity, or judgment attached. We will be forever grateful for this new foundation upon which young historians will surely build grand houses of historical scholarship.

California’s Native People

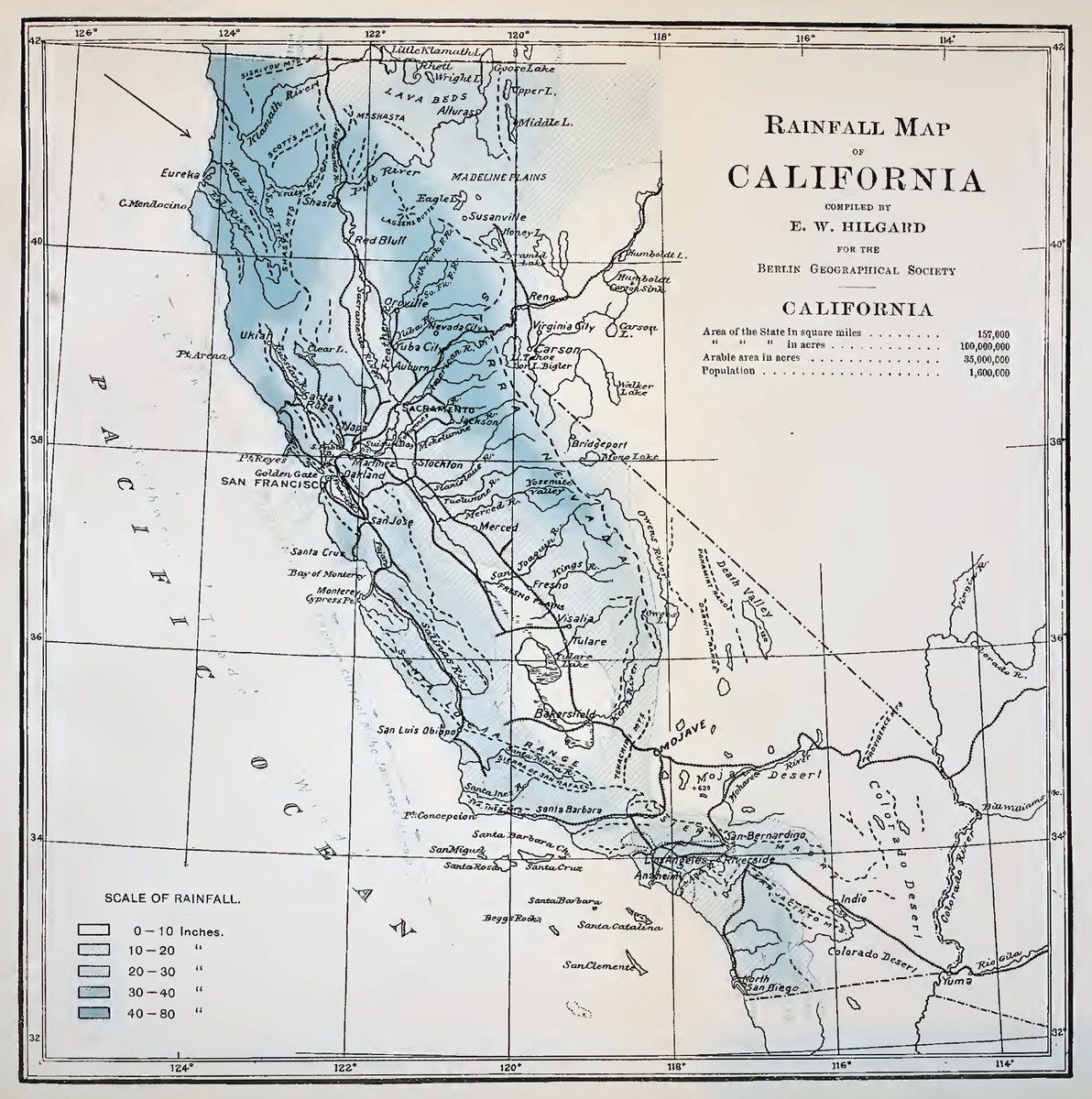

In the diverse and expansive landscape of California, understanding the lives of its first peoples—California's Native communities—requires a journey not just across geography but through time. The state's varied climates and ecosystems shaped the lifeways of countless tribes, each adapting uniquely to their environments yet often sharing common threads in material culture, governance, and spiritual practices.

In the misty rainforests of the Northwest, tribes like the Tolowa, Shasta, Karok, Yurok, Hupa, Whilikut, Chilula, Chimarike, and Wiyot carved out lives intertwined with the rivers and towering redwoods. Their villages hugged the banks of waterways, connected by thousands of trails and the steady glide of dugout canoes, expertly crafted from redwood trees—felled with fire and split with elkhorn wedges.

These tribes built rectangular, gabled homes from redwood and cedar planks and mastered the art of twined basketry, a tradition that not only endured but flourished into the twentieth century. Their spiritual lives centered around the World Renewal ceremonies each fall, designed to stave off natural disasters—earthquakes, floods, poor salmon runs—reflecting a profound connection between ritual and environmental stewardship. Governance rested with wealthy lineage leaders, emphasizing private ownership of resources like oak groves and fishing grounds, underlining the cultural value placed on wealth and status.

The Modoc, Achumawi, and Atsugewi thrived in the diverse landscapes of the Northeast, where the terrain shifts from acorn-rich woodlands to high desert plains. Their diets mirrored this diversity, including salmon and acorns, grass seeds, tubers, rabbits, and deer. Tule plants served dual purposes: food and materials for mats and shelter coverings.

Volcanic mountains provided obsidian, a prized trade commodity. Social structures were independent yet interconnected through marriage alliances. But this region also bore witness to profound trauma. Vigilante violence and disease decimated populations after European contact. The Modoc's fierce 1872 resistance against forced relocation to Oregon marked one of California's last stands for Native sovereignty. However, some tribes secured public land allotments, like the XL Rancheria in 1938 (established as a reservation for Native Americans, specifically the Pit River-Paiute Tribe in Modoc County, California). Many, including the Modoc, faced tragic exile to distant lands. The Modoc were not the only group that violently resisted the Spanish missions.

Spanning vast valleys and Sierra slopes, Central California was home to tribes such as the Pomo, Maidu, Yokuts, Miwok, Wintun, and many others. Despite ecological diversity, the region's tribes shared bountiful resources—acorns, salmon, deer, elk, and antelope.

Basketry reached unparalleled artistry here, with Pomo craftsmen renowned for intricate designs. Both coiled and twined techniques flourished, surviving colonial suppression to become symbols of cultural identity. Semi-subterranean roundhouses hosted Kuksu dances, rituals that ensured the renewal of natural resources. Villages ranged from small, self-sufficient hamlets to bustling communities of up to 1,000 people, sustained by specialized artisans and abundant food supplies.

A Lakisamni Yokuts named Estanislao would lead a rebellion against the Spanish. Estanislao, a former mission Indian and alcalde (local leader) at Mission San José, named after the Polish Saint Stanislaus, led a significant rebellion in 1828. Drawing from his experience within the mission system, Estanislao organized a formidable resistance of over 400 warriors (which would grow to nearly a thousand ex-neophyte and gentile warriors), many of whom were fugitive mission Indians. Estanislao issued a ringing challenge to the Mexican authorities: “We are rising in revolt. . . . We have no fear of the soldiers, for even now they are very few, mere boys . . . not even sharpshooters.” Utilizing his Spanish fluency as a tool of defiance and guerrilla tactics and knowledge of Spanish military strategies, his forces waged a series of successful battles against 100 Mexican troops under the leadership of Lieutenant Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo before ultimately being overpowered. Despite the defeat, Estanislao’s rebellion symbolized the enduring resistance and agency of California's Native communities.

Southern California's tribes, including the Chumash, Gabrielino, Luiseno, Cahuilla, and Kumeyaay, navigated a landscape as varied as their cultures—from the windswept Channel Islands to arid deserts. The Chumash's “tomols,” sleek planked canoes crafted by secret guilds, linked island and mainland communities, fostering robust maritime trade.

Villages ranged from desert hamlets to Chumash settlements of over a thousand people. Homes were often conical, made from arrowweed and tule, while coastal communities incorporated whale bones into structures. Soapstone quarries on Catalina Island provided material for vessels and pipes.

Leadership varied, with chieftains (sometimes women) organizing community life, assisted by shamans and ritual specialists. The hallucinogenic jimsonweed featured in male puberty rites reflects the deep spiritual currents woven through daily life. These tribes were among the first to confront European colonization, an encounter that irrevocably altered their world. One notable figure of resistance was Toypurina, a Tongva medicine woman who led a rebellion against Spanish authorities at Mission San Gabriel in 1785, protesting the occupation of her ancestral lands.

The Spanish arrival in 1769, led by Junipero Serra and Gaspar de Portola, marked the beginning of a coercive mission system—religious labor camps masked as benevolent institutions. Missions were established not just to convert but to control, using soldiers, bribes, and the devastating power of European diseases to subjugate Native populations.

Epidemics—smallpox, measles, diphtheria—ravaged tribes with no immunity, decimating communities and eroding traditional social structures. Mission registers reveal an alarming infant mortality rate, with more than half of the mission-born children dying before age five. Despite these devastating conditions, Native cultures persisted. Historian Lisbeth Haas has demonstrated that preconquest traditions and identities survived, resisting the Spanish goal of complete assimilation.

Despite overwhelming oppression, Native resistance was fierce and persistent. Covert worship of traditional deities, fugitive escapes, and even assassinations of missionaries punctuated life under Spanish rule. Armed revolts erupted, from the Kumeyaay's destruction of Mission San Diego in 1775 to the Chumash uprising of 1824, where missions were seized, burned, and abandoned. The Chumash revolt was triggered by the mistreatment of neophytes and harsh mission conditions, with thousands joining the fight for autonomy.

Fugitive bands, armed and mounted, waged guerrilla warfare against colonial forces, disrupting mission stability and asserting Native agency. Even within mission walls, cultural identities persisted—tribal languages were spoken, traditional housing maintained, and elders passed down ethnographic knowledge that survives today. Resistance also took subtle forms: graffiti on mission walls, clandestine rituals, and reinterpreted religious art served as quiet acts of defiance.

With Mexican independence in 1821, missions were supposed to transition land back to Native communities in 1823, as it was initially a ten-year period after the establishment of each mission, though that never materialized. Instead, anti-clerical policies and settlers seeking their own opportunity led to widespread dispossession. Though Mexico's 1824 constitution declared Indians citizens with voting rights, in practice, they remained marginalized, their lands and labor exploited.

Yet, amidst dispossession and decline, Native tribes endured. Their histories—marked by resilience, resistance, and the unbroken thread of cultural continuity—remain integral to understanding California's past and present. The history of Native Californians is a narrative of resilience in the face of overwhelming challenges. From the arrival of the Spanish to the impact of American expansion, Indigenous communities have faced repeated autonomy and erased their cultures. Yet, their ability to adapt and resist has ensured their presence remains integral to California's story. Understanding this complex history is crucial for appreciating the depth of Native American contributions to the state's cultural and social fabric.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

California State Board of Trade.

California: Early History, Commercial Position, Climate, Scenery, Forests, General Resources ... 1897–98. San Francisco: California State Board of Trade, 1898.

Castillo, Edward D. “Short Overview of California Indian History.” State of California Native American Heritage Commission. State of California, 2020.

Cherny, Robert W., Gretchen Lemke-Santangelo, and Richard Griswold del Castillo. Competing Visions: A History of California. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Wadsworth, 2014.

Rawls, James J., and Walton Bean. California: An Interpretive History. 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012.

Quote, p. 61: “We are rising in revolt. . . . We have no fear of the soldiers, for even now they are very few, mere boys . . . not even sharpshooters.”

Haas, Lisbeth. Conquests and Historical Identities in California, 1769–1936. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1995.

National Museum of the American Indian. “Estanislao’s Rebellion: Source H.” Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.