Wizard of Wall Street

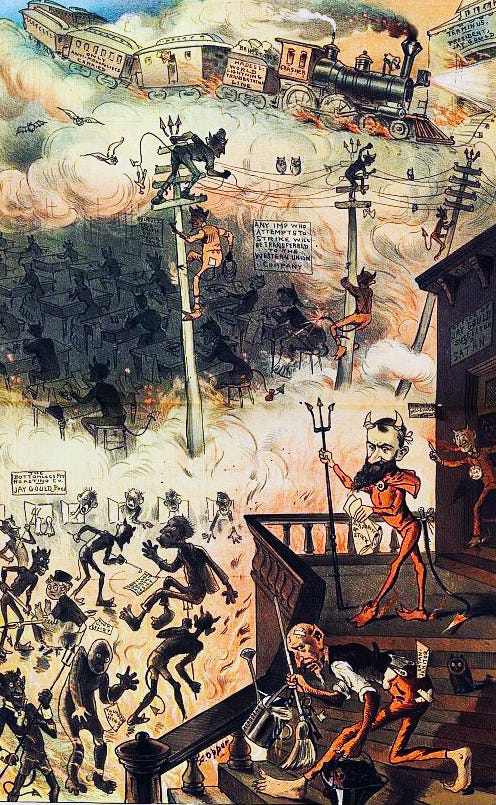

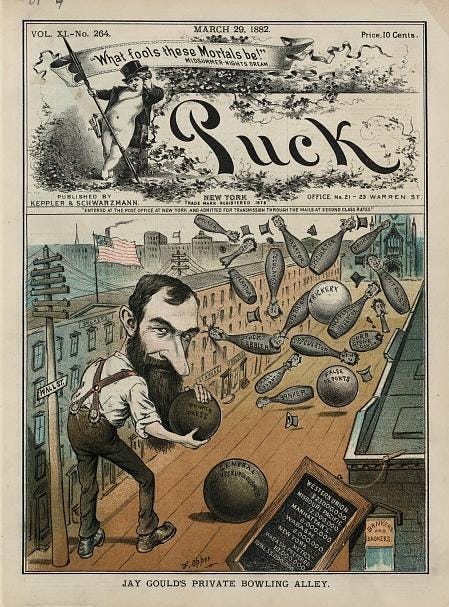

In the somber days of late December 1892, Jesse Seligman, a financier and longtime friend of Jay Gould, reflected on the legacy of the man whose empire had reshaped America’s economy. Speaking to a reporter from the New York Tribune, Seligman could sense the rush of history’s judgment bearing down on his friend, now buried just a week. “The most misunderstood, most important, and most complex entrepreneur of this century,” Seligman said of Gould. And yet, Gould, whose empire encompassed the Western Union Telegraph Company, the Missouri Pacific Railroad, and the Manhattan Elevated Railroad, was painted in history as the singular villain of his era. Seligman felt different.

“If Gould was a sinner,” Seligman posed, “exactly who were the saints?”

It was a fair question that Seligman answered with a surgeon’s precision. Could Cornelius Vanderbilt, the old Commodore himself, honestly be held up as a paragon of virtue? After all, Vanderbilt’s only stated agenda was his personal gain, famously dismissing pleas to aid the poor with a smug line about his success: “Let them do what I have done.”

And what of Daniel Drew, the devout founder of the Drew Theological Seminary? Drew, Seligman recalled, had built his fortune through the same unscrupulous tactics as Gould, watering stocks with the same vigor he once watered his cattle. Even John D. Rockefeller, who had played a key role in the cutthroat Erie Railroad battles, was hailed as a titan of industry despite his monopoly-crushing ambitions.

So why was Gould’s name dragged lower in the mud than the rest? Seligman couldn’t reconcile it. True, Gould’s methods—his manipulations during the infamous Erie Wars or his 1869 scheme to corner the gold market—were undoubtedly shady. But was he truly worse than his peers in the ruthless arena of 19th-century capitalism? To understand Jay Gould, one must dig deeper than the caricatures of a robber baron.

Definition

Robber baron

rob·ber bar·on, noun: robber baron; plural noun: robber barons

a person who has become rich through ruthless and unscrupulous business practices (originally with reference to prominent US businessmen in the late 19th century).

Sentence: “both political parties served the interests of the corporate robber barons.”

Wizard of Wall Street

Born in 1836 in Roxbury, New York, Jay Gould's ascent from modest beginnings to the zenith of Wall Street power epitomized the relentless drive of the Gilded Age. His railroads and telegraphy ventures were marked by innovation and controversy, painting him as a figure of both admiration and scorn.

Gould’s strategic acumen was evident in his consolidation of failing railroads into profitable enterprises, notably the Union Pacific. His influence extended to the telegraph industry, where he played a pivotal role in shaping Western Union into a dominant force. Yet, his aggressive tactics—ruthless takeovers, market manipulations, and fierce rivalries—earned him the scarlet letter of a “robber baron,” a term that underscored the ethical complexities of his methods.

The simplistic vilification of Gould leaves much to be challenged and urges a much more nuanced understanding of the era’s capitalist ethos. At a time when economic expansion often blurred ethical lines, Gould’s actions mirrored the complexities of a society grappling with the costs of progress. Thus, Jay Gould's legacy remains a testament to the intricate dance between innovation and exploitation, prompting us to reflect on the true nature of sin and sainthood in the annals of American enterprise.

In 1852, a young Jay Gould, just sixteen years old, set out to carve a future with little more than his intellect and ambition. Armed with a rudimentary education and an insatiable drive, he took on the role of mapmaker and surveyor. The rolling hills of New York became his first canvas as he plotted roads and townships meticulously. However, Gould was not content with being a mere laborer. Soon, he struck out on his own, turning his knowledge of the land into a lucrative business, publishing maps that locals eagerly purchased. In the quiet but determined hustle of surveying and publishing, it was here that Gould’s entrepreneurial instincts first shone. He was learning how to see opportunity where others saw only unbroken ground and how to transform potential into profit.

By 1856, Gould had left the rolling hills and winding roads behind, turning his attention to the dense forests of Pennsylvania. Gould entered the tannery business through the guidance of Zadock Pratt, a seasoned leather magnate. Here, he learned the art of enterprise on a grander scale. Pratt taught him to see the value hidden in raw resources—the towering hemlocks that would become leather goods, the untapped wealth of a burgeoning industrial nation. Gould’s ambitions soon outgrew even this rugged landscape. He bought out his mentor’s stake and began venturing beyond the tannery. The forests had taught him lessons in resource management and bold investment, but the rumble of the railroads called louder still.

Then came 1859, a pivotal year in Gould’s ascent. With the confidence of a man twice his age, he acquired the failing Rutland & Washington Railroad. Where others saw rusting tracks and financial ruin, Gould saw possibility. His reforms turned the railroad into a profitable enterprise, displaying for the first time the brilliance—and the cold calculation—that would define his career. This was not simply business acumen; it was the work of a strategist.

Jay Gould’s rise in these years was not just a story of personal ambition. It was the story of a young America, restless and expanding, eager for new frontiers to conquer and exploit. As he laid his first tracks and plotted his first enterprises, Gould laid the groundwork for an empire that defined an era.

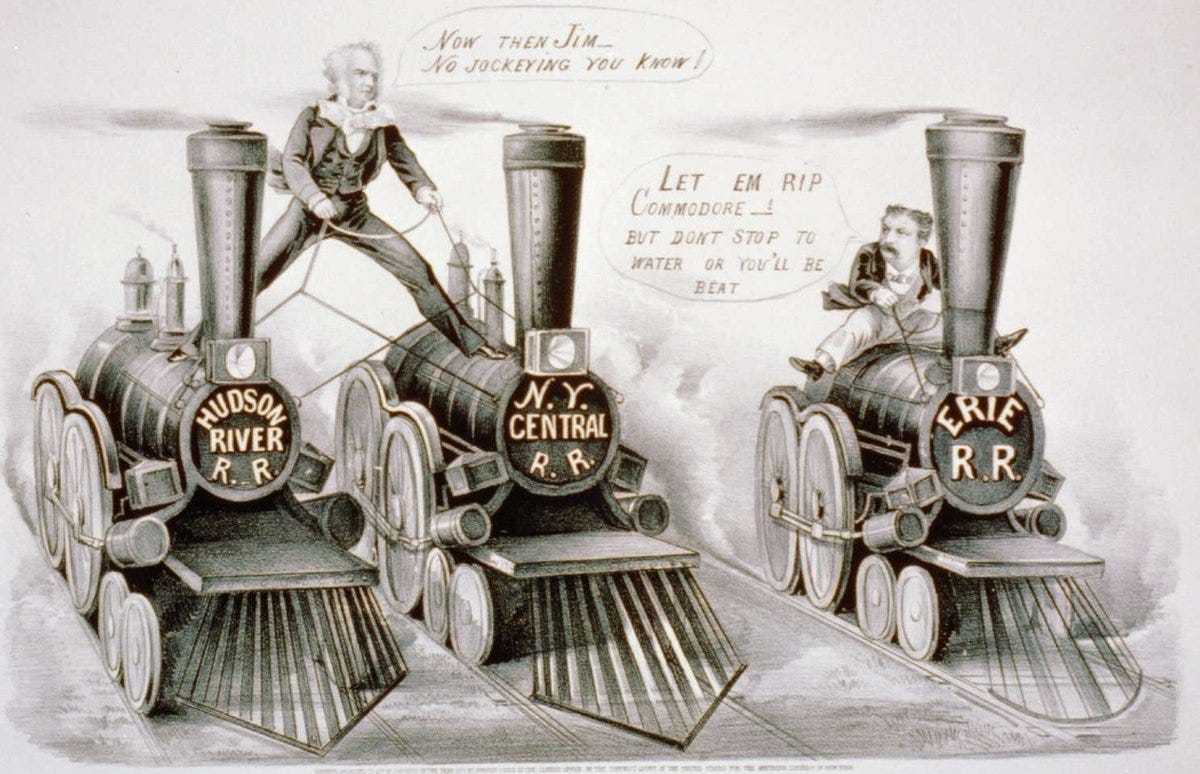

The Erie Wars: Gould vs. Vanderbilt

By the late 1860s, Wall Street was a battlefield, and the spoils were control of the Erie Railroad. For Jay Gould, now a rising figure in American finance, this was more than a business opportunity—it was a declaration of war against Cornelius Vanderbilt, the Commodore himself. Vanderbilt, who had already secured dominance in shipping and railroads, sought to add the Erie to his empire, seeing it as the last piece in his grand vision of a unified transportation network stretching across the northeastern United States. Gould, younger, shrewder, and no less ambitious, had other plans.

The Erie Wars were not fought with armies. Instead, they were fought with lawyers, brokers, and reams of freshly printed stock certificates. In 1867, Vanderbilt began quietly purchasing Erie stock, driving the price to corner the market. Gould and his colorful and equally daring allies, Daniel Drew and James Fisk, countered by flooding the market with millions of new, unauthorized shares. Unaware of the scheme, Vanderbilt bought these shares at inflated prices, losing millions as Gould and his compatriots pocketed the profits.

The drama spilled into the courts, where Vanderbilt’s legal team sought to undo Gould’s maneuvers. Gould responded with an audacity that stunned even seasoned financiers. When a judge ruled against him, he allegedly bribed the New York legislature to pass laws favorable to his position. His team also fled to New Jersey with the Erie Railroad’s treasury in tow, setting up a temporary headquarters in a Hoboken hotel—appropriately nicknamed "Fort Erie."

Eventually, a fragile truce was reached. Vanderbilt received a substantial payout, and Gould retained control of the Erie. But the episode left a lasting impression of Gould as a master of strategy, a man unafraid to play both sides of the law to achieve his ends.

The Gold Ring of 1869: A Day-by-Day Account

The Prelude

In early 1869, Jay Gould, a financier with a growing empire, turned his ambitions toward the gold market. Working with his close associate James Fisk, Gould devised a scheme to corner the market, artificially inflating the price of gold and controlling its supply. Gould and Fisk needed political leverage to achieve this, which they sought through Abel Corbin, President Ulysses S. Grant’s brother-in-law. Corbin became the linchpin of their operation, using his proximity to President Grant to influence government policy.

Their plan hinged on preventing the federal government from releasing gold reserves into the market, which would otherwise disrupt their corner. Gould and Fisk began quietly buying large quantities of gold, driving the price upward while maintaining a façade of legitimate trading activity.

Jay Gould initially brought Corbin into the conspiracy by outlining his plan and promising substantial financial incentives. Gould purchased $1.5 million worth of gold in Corbin’s name and assured him all profits would be his to keep. For every percentage point increase in the price of gold, Corbin stood to gain $15,000—a staggering sum for the era. Eager to capitalize on his connections, Corbin claimed to wield influence with President Grant, once boasting to Gould, “I am right behind the throne. Give yourself no uneasiness. All is right.”

The conspirators sought to manipulate government policy to ensure their success. Gould and Corbin strategized to prevent the federal Treasury from selling gold reserves, which would have increased supply and undermined their efforts to inflate prices. Corbin worked to sway appointments to critical Treasury posts, securing the placement of General Butterworth as Assistant Treasurer in New York. Butterworth, later exonerated by Congress, reportedly held $1 million in gold on Gould’s behalf.

Corbin, Gould, and Fisk attempted to gauge Grant’s stance on economic policy. They arranged meetings with the president and even orchestrated social events, including a lavish banquet aboard one of Fisk’s steamers. Despite these efforts, Grant remained largely aloof, delivering cryptic remarks that offered little clarity to the schemers. A comment about the “fictitiousness of the country’s prosperity” led Gould to worry Grant might intervene to deflate the bubble.

Monday, September 13, 1869

Gould and Fisk’s purchases had begun significantly impacting the market by this date. The price of gold steadily rose from $132 to $141 per ounce. Speculators began to notice, but few understood the scale of the operation or its architects.

Wednesday, September 15, 1869

Corbin assured Gould and Fisk that President Grant would not intervene in the market, emboldening the duo to increase their holdings. The price of gold reached $144, further alarming speculators. Meanwhile, rumors swirled in financial circles about unusual activity, sparking unease among traders.

Friday, September 17, 1869

When the gold price hit $147, market anxiety deepened. Gould continued buying quietly while Fisk made louder, more visible purchases, adding to the growing panic. Newspapers began speculating about manipulation, but Gould and Fisk dismissed such claims publicly.

Monday, September 20, 1869

Gould and Fisk had accumulated an enormous position in gold, and prices climbed to $150. Their strategy relied on creating a sense of inevitability—that prices would only go higher—forcing other traders to buy at inflated rates.

Wednesday, September 22, 1869

President Grant, becoming suspicious of the market’s erratic behavior, consulted with Treasury Secretary George S. Boutwell. Sensing that Grant might intervene, Gould began discreetly selling some of his gold holdings to reduce his exposure—though Fisk remained confident in their market control.

Friday, September 24, 1869 – Black Friday

The morning dawned clear and calm, but the tension in New York’s financial district was palpable. By 9 a.m., the streets surrounding the Gold Exchange were teeming with speculators, brokers, and curious onlookers. Gould and Fisk’s actions had driven the price of gold to staggering heights, with bids reaching 150% above the standard rate. The market churned with frenzied activity, and even seasoned operators were thrown into chaos.

The bubble burst spectacularly. Early in the morning, gold prices skyrocketed to $162 per ounce as panicked traders scrambled to buy before prices climbed further. The frenzy peaked by mid-morning, but at 11:00 a.m., President Grant ordered the Treasury to act. Inside the Gold Room, pandemonium reigned. Brokers screamed over each other to make trades, their faces pale with anxiety as they watched the price climb to $162.50. The financial district seemed on the brink of collapse as mobs gathered in front of brokerage houses, demanding answers and threatening violence.

Corbin’s role began to unravel when President Grant became suspicious. A letter from Mrs. Grant to Mrs. Corbin advised Mr. Corbin to sever any ties to Wall Street speculations, effectively cutting him off from Gould’s scheme. The message devastated the conspirators, with Gould reportedly declaring, “If you show that note, I am a ruined man.” Gould attempted to retrieve the gold held in Corbin’s name and pay him his promised profits, but the situation deteriorated rapidly.

By midday, the scene took a decisive turn. Word spread that the federal government had intervened on orders from President Grant. Treasury officials released $4 million in gold reserves into the market, breaking Gould and Fisk’s corner. Prices plummeted almost instantly, falling to $133 by the end of the day. Among those caught in the storm, some firms dissolved entirely, their reputations and fortunes swept away. The fallout was catastrophic, summed up by the story of Albert Speyer, who reportedly lost control of himself, and his hair turned white overnight due to the stress of the collapse. Wealth evaporated in minutes, leaving brokers, banks, and speculators devastated.

Then there was the haunting question shouted amid the turmoil, “Who killed Leupp?”—referring to Charles M. Leupp, a leather merchant associated with Jay Gould in earlier years. Leupp had committed suicide years prior under the weight of financial strain partly tied to Gould’s dealings. This rhetorical cry of blame resonated during Black Friday as emotions ran high and tensions escalated.

Fisk and Gould, however, managed to avoid total ruin. Gould, who had foreseen the crash, had quietly sold off much of his position the day before. Fisk, ever the showman, bore the brunt of public outrage, even narrowly escaping a mob attack outside his office. Black Friday exposed the fragility of Gilded Age finance and the dangers of unregulated speculation. It forever stained the reputations of its principal architects, yet their audacity and cunning remained a symbol of the era’s ruthless ambition.

The Aftermath

Ultimately, Corbin’s involvement highlights the blurred lines between personal relationships and financial schemes during the Gilded Age. His proximity to power offered Gould and Fisk an opening but added a layer of risk that would contribute to the conspiracy’s downfall on Black Friday. The scandal tarnished the Grant administration, exposing the dangers of unchecked speculation and the vulnerabilities of the financial system. Congressional hearings followed, with Gould and Fisk denying any wrongdoing, though their involvement was evident. The Gold Ring of 1869 remains a defining moment in the history of Wall Street, showcasing both the audacity of Jay Gould and the chaotic, unregulated nature of Gilded Age capitalism.

Jay Gould & the Consolidation of Power

1873: Entering the Union Pacific

In 1873, as America staggered under the weight of a financial panic, Jay Gould saw an opportunity amid the chaos. The Union Pacific Railroad, still recovering from the infamy of the Crédit Mobilier scandal, was struggling to find its footing. Gould, with his characteristic audacity, began acquiring shares in the company, sensing the immense potential of the transcontinental line.

Gould’s vision extended far beyond merely operating a railroad. He saw the Union Pacific as a gateway to unprecedented profits and control over the arteries of the nation’s economy. By 1875, he had secured substantial company control, stabilizing its finances and expanding its reach into untapped markets. The Union Pacific became a cornerstone of Gould’s railroad empire, connecting the American heartland to global trade routes. For Gould, it wasn’t just about moving goods—it was about consolidating power on a scale few had imagined.

In 1880, Gould turned his attention from rails to wires. Western Union, the dominant telegraph company, was critical to the nation’s communication infrastructure. Steadily acquiring shares, Gould orchestrated a masterful takeover, adding Western Union to his vast portfolio of controlled assets.

This acquisition was more than a business coup; it gave Gould unparalleled influence over the flow of information in the United States. With Western Union under his control, he effectively monopolized the nation’s telegraph lines, a network that stretched coast to coast. In Gould’s hands, Western Union became a tool for communication and consolidating industrial and financial power.

1886: The 11,000-Mile Empire and the Great Railroad Strike

By 1886, Jay Gould’s railroad holdings had reached an astonishing 11,000 miles, stretching from the Midwest to the Gulf of Mexico. The Missouri Pacific, the Texas and Pacific, and other lines formed the backbone of his empire. Yet, the scale of Gould’s operations also made him a lightning rod for labor unrest. In March 1886, the great Southwest Railroad Strike erupted, sparked by wage cuts and harsh working conditions on Gould-controlled lines. The strike, led by the Knights of Labor, quickly escalated into a nationwide conflict, with tens of thousands of workers walking off the job. Gould, ever calculating, refused to negotiate, banking on the federal government and local authorities to quell the unrest.

The violence was unprecedented. Strikers clashed with police and private security forces in bloody confrontations across Missouri, Arkansas, Texas, and beyond. In Fort Worth, Texas, armed guards fired on striking workers, leaving several dead—rail traffic ground to a halt, crippling commerce in the region and leaving the nation on edge. Gould’s refusal to back down was a testament to his steely resolve and disdain for organized labor. “I can hire one half of the working class to kill the other half,” he is rumored to have said, a chilling summation of the era’s brutal labor relations. By June, the strike collapsed, leaving the Knights of Labor severely weakened and Gould’s empire intact.

1892: Death and Legacy

Jay Gould died on December 2, 1892, at 56, leaving behind an estate valued at approximately $72 million—a staggering sum in the 19th century. Despite his wealth, Gould’s health had been frail for years, his tireless work ethic and constant scheming taking their toll.

Gould’s death marked the end of an era, but his legacy endured. He had built an empire that reshaped the American economy, linking distant regions through railroads and revolutionizing communication through telegraphy. Yet, he was also a symbol of the excesses of the Gilded Age—a man whose relentless pursuit of power left a trail of broken competitors, exploited workers, and economic volatility.

To some, Gould was a visionary who helped lay the foundation of modern America. To others, he was the archetype of the robber baron, a man whose wealth was built on the backs of the working class. Either way, Jay Gould’s story remains one of American history's most compelling narratives of ambition, ingenuity, and controversy.

Perhaps, as Seligman suggested, the moral lines were never as clear as critics would have them. Gould’s life reflected his times—an age of opportunity, exploitation, immense wealth, and staggering inequality. He was no saint, but neither was he the devil incarnate. His legacy, like the Gilded Age itself, defies easy judgment. In the end, the question persists: If Gould was a sinner, exactly who were the saints?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Halstead, Murat, and J. Frank Beale Jr. Life of Jay Gould: How He Made His Millions. Edgewood Publishing Co., 1892.

Northrop, Henry Davenport. Life and Achievements of Jay Gould, the Wizard of Wall Street. Bridgeport, CT: Union Book Company, 1892.

Renehan Jr., Edward J. Dark Genius of Wall Street: The Misunderstood Life of Jay Gould, King of the Robber Barons. New York: Basic Books, 2005.

Schumacher, Cassandra. Cornelius Vanderbilt: Railroad Tycoon. New York: Cavendish Square, 2019.

Footnotes

Quote: “The most misunderstood, most important, and most complex entrepreneur of this century,” Seligman, Jesse. Interview with New York Tribune, December 1892. Quoted in Maury Klein, The Life and Legend of Jay Gould, preface page.

Quote: “Let them do what I have done,” Cassandra Schumacher, Cornelius Vanderbilt: Railroad Tycoon (New York: Cavendish Square, 2019), 79.