Introduction

Seismic shifts in industry, economics, and society marked the late 19th century in America. As the country’s industrial base expanded, it brought unprecedented wealth to a small elite and widespread suffering to the working masses. In response, various movements arose to challenge the inequities of this new industrial age, each offering its vision of reform or revolution: the labor movement, the anarchist movement, the populist movement, and the socialist movement. Together, they waged a multifaceted struggle against the forces of capital, often confronting violent repression in their quest for justice.

The Labor Movement

The labor movement emerged as a powerful force in response to grueling working conditions, low wages, and a lack of basic workplace protections. Laborers toiled in dangerous factories, mills, and mines, often 12 to 16 hours a day, six days a week. Unions such as the Knights of Labor and the American Federation of Labor (AFL) sought to organize workers across industries to demand shorter hours, better pay, and safer working conditions.

The late 19th century also saw dramatic labor strikes, including the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. In this strike, workers nationwide halted rail traffic in protest against wage cuts. The strike spread like wildfire, with workers clashing violently with militia and federal troops. It revealed both the power of worker solidarity and the brutal response it could provoke from the state.

The Anarchist Movement: Confronting Capital and the State

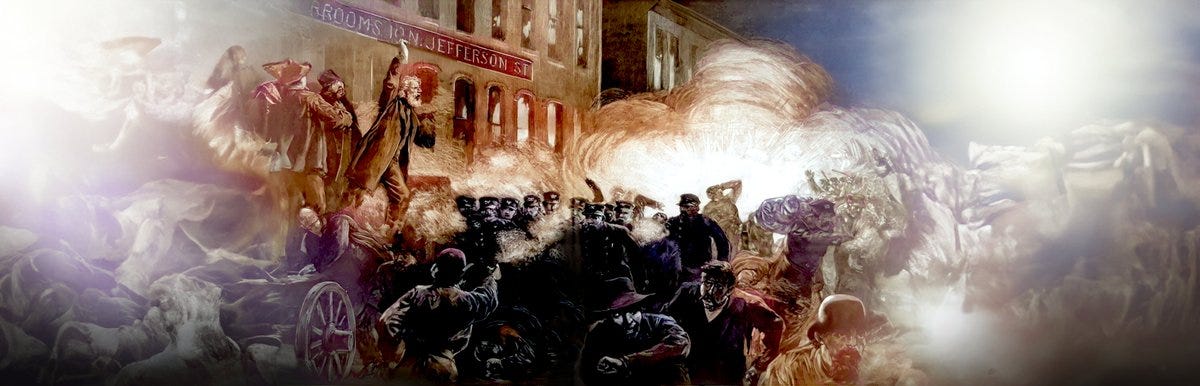

Often overlapping with labor activists, anarchists sought to dismantle capitalist systems and the state itself. They believed the two were inextricably linked and that freedom could only come through their destruction. Events such as the Haymarket Affair in Chicago in 1886 epitomized the anarchist struggle and its violent repression. Following a bomb explosion at a labor rally, police arrested and convicted several anarchist leaders in a trial widely regarded as unjust.

Anarchist thinkers such as Emma Goldman advocated not only for economic justice but also for gender equality, free speech, and other radical reforms. As she declared, “The history of progress is written in the blood of men and women who have dared to espouse an unpopular cause, as, for instance, the black man's right to his body, or woman's right to her soul.” Their uncompromising critique of power structures made anarchists a target of state violence and media demonization.

The Populist Movement: Farmers Rise Against Exploitation

In the rural heartlands, farmers were organizing their own resistance against exploitation by railroads, banks, and grain elevator operators. The Populist Party, also known as the People’s Party, was founded in 1892 as a coalition of farmers, laborers, and reformers. It called for the nationalization of railroads, the free coinage of silver to inflate crop prices, and the establishment of a graduated income tax.

The Populist platform, as expressed in the Omaha Platform of 1892, articulated the grievances of an agrarian America that felt abandoned by industrial capitalism. “The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few,” the platform declared, capturing the deep frustration of those who saw the American Dream slipping out of reach. Despite their regional strength, the Populists faced opposition from powerful corporate interests and a political establishment aligned with industrial capital.

The Socialist Movement

The socialist movement in late 19th-century America sought to address the same inequities as other movements but with a more systemic critique of capitalism itself. Figures such as Eugene V. Debs, who helped found the Socialist Party of America, argued for public ownership of major industries and the redistribution of wealth.

Socialists often aligned with labor struggles, particularly during dramatic conflicts like the Pullman Strike of 1894. During this nationwide strike against wage cuts and high rents in company-owned housing, federal troops intervened, leading to bloody clashes and the deaths of dozens of workers. Debs, imprisoned for his role in the strike, emerged as a national figure, proclaiming that “the issue is socialism versus capitalism. I am for socialism because I am for humanity."

Repression and Legacy

Each of these movements faced fierce opposition from the state and corporate powers. Strikers were met with armed militia, anarchists were imprisoned or executed, and the political system marginalized populists. Yet their struggles left a lasting impact. They forced the nation to confront the inequalities of the Gilded Age and laid the groundwork for the progressive reforms of the early 20th century.

In their own ways, the labor, anarchist, populist, and socialist movements represented the dreams and frustrations of millions of Americans. They fought for material gains and a more just and equitable society, leaving behind a legacy of resistance and hope that continues to inspire.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Corbett, P. Scott, Volker Janssen, John M. Lund, Todd Pfannestiel, Paul Vickery, and Sylvie Waskiewicz. U.S. History. Houston, TX: OpenStax, Rice University, 2014.

Locke, Joseph, and Ben Wright, eds. The American Yawp.

Schweikart, Larry, and Michael Allen. A Patriot's History of the United States: From Columbus's Great Discovery to the War on Terror. New York: Sentinel, 2004.

Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. New York: Harper & Row, 1980.

Quote: “The history of progress is written in the blood of men and women who have dared to espouse an unpopular cause, as, for instance, the black man's right to his body, or woman's right to her soul.” Emma Goldman, Anarchism and Other Essays, ed. Richard Drinnon (New York: Courier Dover Publications, 1969), 340.

Quote: “The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few.” The People’s Platform: Historical Documents of American Populism, ed. Gregory A. Fossedal (New York: Algora Publishing, 2007), 955.

Quote: “the issue is socialism versus capitalism. I am for socialism because I am for humanity.” Howard Zinn, The Twentieth Century: A People's History (New York: Harper Perennial, 2003), 182.