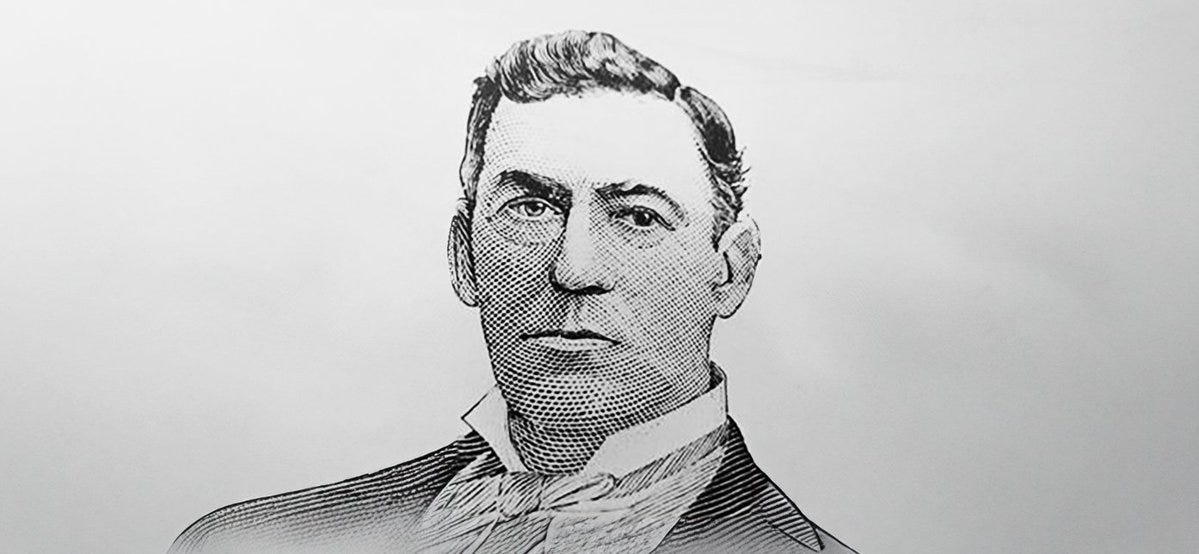

It was your average autumn evening in New Orleans, October 1890, when Chief of Police David Hennessy was shot down in cold blood. Hennessy, a respected officer known for his unflinching stance against organized crime, had made enemies, and they finally came for him. He was ambushed as he returned home, and with his dying breath, he was said to have whispered a single word: "Dagos."

The accusation alone was enough to set the city ablaze. Italians, particularly Sicilians, had long been viewed with suspicion in New Orleans. Many were recent immigrants, often poor, often forming tight-knit communities that outsiders did not understand. Some among them were involved in criminal enterprises—organized, secretive, and increasingly bold. But the majority were hardworking, law-abiding, trying to carve out their place in a new world.

From the moment Hennessy fell, his murder was seen as more than just a crime. It was a declaration of war. Within hours, the police began sweeping through the Italian quarter, rounding up suspects. More than 150 men were arrested in the ensuing crackdown, among them prominent Sicilian businessmen and laborers alike. One of the men taken into custody was Joseph Macheca, a well-known merchant with deep connections in the city. Others included the Matrongas, a family reputed to be at the center of the city’s underworld dealings. Evidence was scarce, but the pressure to find justice—or vengeance—was mounting.

The trial was a spectacle. The city’s most powerful men, including Mayor Joseph Shakespeare, declared that New Orleans was under siege by lawless secret societies. The press, led by major publications such as The Daily Picayune, fanned the flames, repeatedly publishing accounts of a supposed Sicilian “Mafia” operating within the city.

The prosecution’s case relied heavily on dubious testimony from informants of questionable credibility. Yet, to the shock of many, the jury returned with a verdict of acquittal for most of the accused, while others were left in legal limbo due to a hung jury. The courtroom erupted. For many, it was inconceivable that the legal system could fail to punish the men believed to have orchestrated the murder of their city’s chief of police.

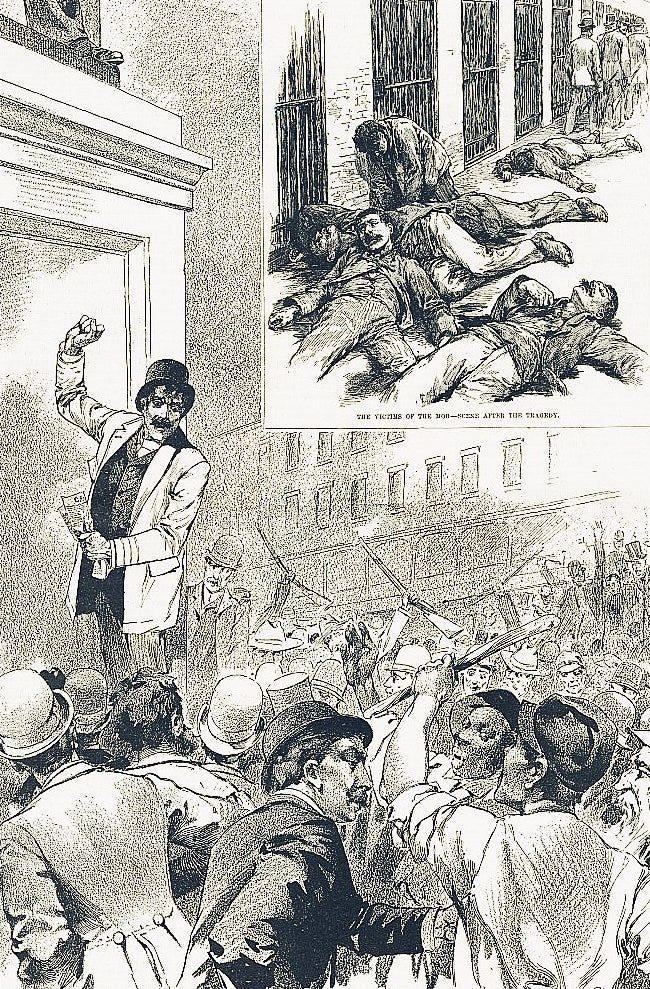

A mob began to form. At first, it was a murmur of anger, then a roar of fury. The night of March 14, 1891, became one of the darkest in the city’s history. Thousands gathered outside the Parish Prison, where the Italians were held. A meeting was called at Clay Square, and within minutes, a group of vigilantes, self-proclaimed as "The Committee of Fifty," called for immediate action. Among the mob were some of the city’s most prominent citizens, urging on the violence, openly declaring that the law had failed and the people must take justice.

Armed men stormed the gates. The prisoners, terrified, huddled together as the angry horde closed in. Shots rang out. Eleven men, some already acquitted, others still awaiting trial, were dragged from their cells and slaughtered. Some were shot where they stood; others were hanged from lampposts. The mob took its time, ensuring a gruesome spectacle. Emmanuele Polizzi, one of the prisoners, was hanged three times before he finally succumbed to death. James Caruso was riddled with more than forty bullets. Their bodies were left to sway in the wind as the crowd cheered.

Tom Duffy, a local tough guy with a penchant for violence, later sought his own vigilante justice. Just days after the lynching, he strode into the prison, demanding to see Antonio Scaffide, one of the accused assassins who had survived the riot. When Scaffide appeared, Duffy pulled a pistol and shot him at point-blank range. "If the Italian dies, I'm willing to hang," he declared as the police hauled him away. "I only wish there were seventy-five more men like me."

The New Orleans press celebrated the mob’s actions. The Cotton Exchange, the Chamber of Commerce, and other institutions of power openly approved. The Italian community, stunned and terrified, found little recourse. Their government, across the Atlantic, was outraged. The Kingdom of Italy lodged formal protests, demanded justice, and even threatened diplomatic action. For the first time, the United States faced an international crisis over the lynching of its immigrants. Italy recalled its ambassador, and tensions between the two nations remained high until the U.S. government agreed to pay reparations to the families of the victims.

Yet, in New Orleans, few showed remorse. Mayor Shakespeare, who had called for an end to the secret societies, stood firm. "This state of affairs has gone on long enough," he declared. "It must be stopped." The Committee of Fifty, a group of influential citizens, vowed to root out the mafia once and for all. The ship Elysia, soon to arrive with 700 new Italian immigrants, was placed under scrutiny. If they could not prove their moral and financial worth, they would not be allowed to disembark.

The lynching was not merely an act of vengeance—it was a racial reckoning. Italians were viewed as a foreign menace, and their presence was seen as a threat to the established social order. The events of 1891 fit into a larger pattern of racial violence in the post-Reconstruction South, where white mobs took the law into their own hands, targeting those they deemed unfit for American citizenship. The brutality of the lynching, the public approval it received, and the lack of legal consequences all underscored the precarious position of Italians in America’s racial hierarchy.

The United States and Italy would eventually reach a diplomatic resolution, with the U.S. offering financial reparations to the families of the victims. But the scars left by the lynching endured. The narrative of Italians as criminals persisted, influencing immigration policy and social perceptions for years to come. It was a warning, a reminder that in times of fear, the rule of law could be as fragile as the paper it was written on. For Italians in New Orleans, it was a moment of reckoning—a stark realization that they were not yet American in the eyes of many.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Borkowski, Nicholas.The Mass Lynching of Italians in 1891 New Orleans: Marking Italians as Racially "Dago." Senior Thesis, Swarthmore College, 2013.

"Chief Hennessy Avenged; Eleven of His Italian Assassins Lynched by a Mob. An Uprising of Indignant Citizens in New Orleans – The Prison Doors Forced and the Italian Murderers Shot Down". The New York Times. March 15, 1891.

"One of Heimessy's Assassins Shot. An Italian Conspiracy." San Jose Mercury-News, Volume XXXVIII, Number 110, 18 October 1890.

"A Prisoner Shot." San Francisco Call, Volume 67, Number 140, 18 October 1890.

"The Work of Hired Assassins." San Francisco Call, Volume 68, Number 141, 19 October 1890.