Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 21, Number 3150, 2 May 1861.

The Albany Evening Journal has published a detailed and credible account of a conspiracy to assassinate President-elect Abraham Lincoln as he passed through Baltimore on his way to Washington. While the author's identity remains unconfirmed, the circumstances surrounding its publication leave little doubt that such a plot existed and that the precautions taken to thwart it were both necessary and wise.

The Conspiracy Uncovered

Some of Lincoln’s associates, having received alarming reports of a plot to murder him en route to Washington, took swift action. They hired a seasoned detective, who was sent to Baltimore three weeks before Lincoln’s scheduled arrival. The detective worked secretly, employing men and women to infiltrate secessionist circles.

It was not long before he uncovered a sworn conspiracy: a band of men, bound by an oath, were plotting Lincoln’s assassination. The leader was an Italian refugee, a Baltimore barber who had taken the name “Orsini,” an apparent reference to Felice Orsini, the Italian nationalist who had attempted to assassinate Napoleon III in Paris in 1858.

The plan was chillingly precise. If Lincoln made it through Baltimore by train, the assassins would position themselves within the crowd, pretending to be supporters. At the given signal, some would fire pistols at Lincoln while others would hurl explosive hand grenades into his carriage. In the ensuing panic and confusion, the killers would escape to a waiting vessel in Baltimore Harbor, which would carry them to Mobile, Alabama, deep within the Confederate States.

Lincoln is Warned

On February 21, 1861, as Lincoln arrived in Philadelphia, the detective rushed to meet with his associates and relayed the full conspiracy details. Lincoln immediately arranged a meeting in his room in the Continental Hotel.

After listening to the detective’s report, Lincoln remained firm. He had two public commitments the next day: First, raising the American flag at Independence Hall, marking the anniversary of George Washington’s birth. Second, a formal reception by the Pennsylvania Legislature in Harrisburg.

“I will keep both engagements,” Lincoln declared, “if it costs me my life.”

However, once those obligations were fulfilled, he agreed to be protected by the detective on the journey to Washington.

The Secret Journey to Washington

After public appearances in Philadelphia and Harrisburg, Lincoln retired to his hotel room in the Jones House, appearing to settle in for the night. But just before 6:00 PM, accompanied by Colonel Ward Lamon, he quietly left the hotel through a side entrance and entered a waiting carriage.

To prevent any warning of his movements, telegraph wires were cut as the special train departed.

At 10:45 PM, the train reached Philadelphia, where the detective met Lincoln and hurried him to the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad depot. A regularly scheduled train had been delayed there, allowing Lincoln and his companions to board the sleeping car unnoticed.

Traveling without disguise, Lincoln was dressed simply in an ordinary traveling suit. The train rolled southward through the night, reaching Washington at 6:30 AM on February 23, 1861. Congressman Elihu B. Washburne was waiting at the station, who escorted the President-elect to Willard’s Hotel, where Senator William H. Seward stood ready to receive him.

The detective, traveling under the alias E. J. Allen, had registered alongside Lincoln at the hotel. But his presence did not go unnoticed, and suspicions quickly arose that he had been instrumental in exposing the assassination plot. He left Washington two days later for his safety, though he had initially planned to stay and witness Lincoln’s inauguration.

The Conspirators and Their Motives

Lincoln’s friends did not doubt the loyalty of most Marylanders. Still, they knew that Baltimore harbored a small but dangerous faction of secessionists who would stop at nothing to prevent his presidency.

The conspirators themselves were a diverse mix. Some, driven by a fanatical zeal, compared themselves to Brutus, believing they were ridding the nation of a tyrant. One conspirator recited passages from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar in preparation for the act. Others were hired assassins, paid in gold, and seen frequenting taverns and gambling halls in the weeks leading up to the plot.

The detective’s agents—including women who had taken positions as domestic servants in the conspirators' homes—kept detailed records of their discussions and documents, along with other conspirators' homes, fully preserved but not immediately made public for security reasons.

Lincoln’s Inauguration Secured

In the days following Lincoln’s arrival in Washington, heightened security measures were implemented to protect him until his March 4 inauguration. His family, meanwhile, traveled separately through Baltimore, using the special train originally planned for him. By the time they passed through the city, telegraph wires had been restored, and news of Lincoln’s safe arrival in Washington had already spread.

Lincoln’s famous words at Independence Hall, where he declared he would uphold his principles “even if it costs me my life,” were no mere rhetoric. They were spoken with full knowledge of the grave threat he faced—a threat that had been thwarted only by the swift and secret efforts of those who uncovered it.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 21, Number 3150, 2 May 1861.

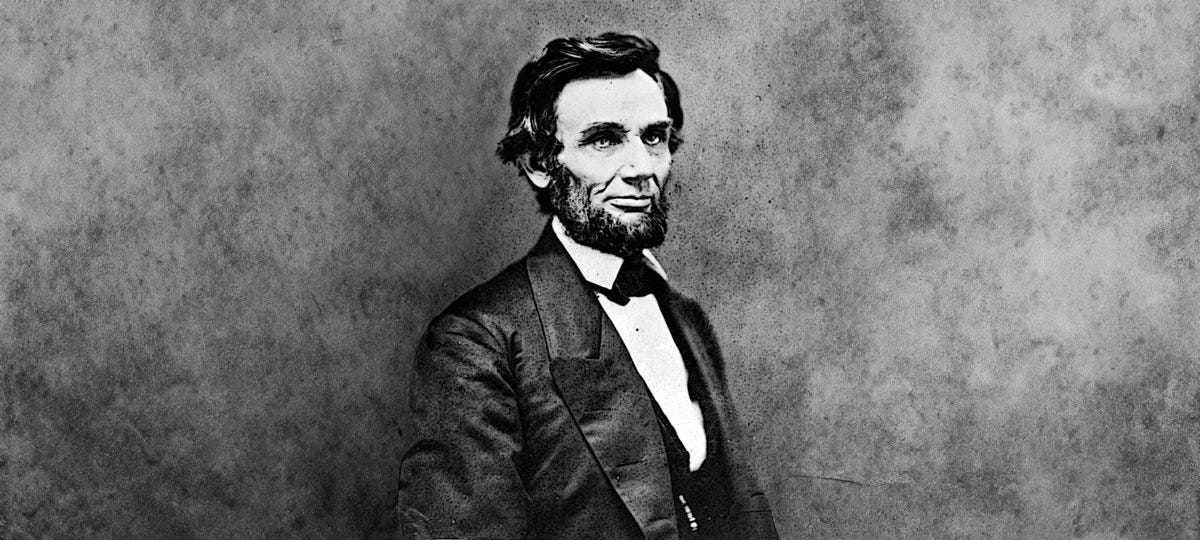

German, C. S., photographer. Abraham Lincoln, last portrait sitting in Springfield, Illinois, before leaving for Washington, D.C., to assume the presidency. Library of Congress,