I have often found myself returning to a single, persistent question: What does it mean to be a historian in today’s world? The answer is not as simple as a degree, a title, or a stack of published papers. It isn’t confined within the walls of a university lecture hall. I realized this in 2021 while sitting in a classroom at the University of California, Irvine in my garage (actually, on Zoom because I was on house arrest like the rest of California during COVID-19, but you get it), enrolled in a course that left an indelible mark on me—History Pedagogy, taught by Professor Laura Mitchell.

Her intellect and passion were nothing short of inspiring. It wasn’t just a course; it was an awakening (for all three students, it's a shame there weren‘t more). Professor Mitchell once remarked, “We are the creators of knowledge at the university, in the Academy.” Those words lingered with me, not as a static truth but as a challenge. I carried them long after the final class, wrestling with their implications. Was that the case?

What, after all, is the job of the historian? It’s a question as old as the discipline itself, yet still as vital today as when Herodotus orated to his students or when Thucydides put his thoughts to scroll. I found the most compelling answer not in dusty archives or lofty texts but in the words of Bob Bain, a scholar I had the great fortune to encounter during Professor Mitchell’s course, who reminded us what history is truly about.

“The historian’s job,” he said with the clarity of someone who’s thought deeply about it, “is to ask historical questions—and to seek better understanding.” Simple, yet profound. It’s not about gathering facts like stamps in an album or reciting dates like incantations. It’s about inquiry. It’s about curiosity. This process, known as historical thinking, is the art of analysis—looking beyond the surface to uncover the complexities beneath.

And here lies the tragedy: this kind of thinking isn’t taught to most American students. Instead, education too often reduces history to a series of disconnected facts memorized for a test and then forgotten. Is it any wonder that scholars are wailing about intellectual stagnation, the so-called “dumbing down” of American students?

We live in an era of abundant information at the tap of a screen, but the information is not understood. In a world awash with data, thinking critically about the past—to ask the right questions and wrestle with the answers—is not just important—it’s essential.

Debates ignite and ripple across social media in an age where history thrives in podcasts. Grand narratives come alive on screens viewed by millions. Can we still claim that the Academy holds exclusive rights to knowledge creation? It’s a question worth asking—not out of defiance, but out of observation.

I don’t hold a Ph.D. or a distinguished academic title. But I did write an article on X, “The Mike Piazza Trade,” and something remarkable happened: it garnered 16,000 impressions almost overnight. Sixteen thousand. It made me pause and wonder—how many impressions would a peer-reviewed journal article receive in its first 24 hours? A hundred? Maybe a few hundred if it catches the right wave in academic circles? I vividly remember a fellow professor and mentor saying, "You should publish this (an article I had written) in a journal so your mom and three people could read it." Yikes!

This isn’t to diminish the value of scholarship but to recognize a shift. The gatekeepers of knowledge are no longer confined to ivy-covered halls or the pages of scholarly journals. Knowledge now travels at the speed of a click, crossing boundaries and reaching audiences that the Academy, for all its rigor and self-aggrandization of its ability to "sort" students, often overlooks the most socially significant and impactful paths and people. Perhaps that’s not a crisis but an opportunity—a reminder that history belongs to those who study it and all who engage with it.

When historians ask who I have studied with, my answer is simple: everyone. I read books, I am primarily an autodidact, and yes, I am a professor. But if I have a seat in the ivory tower, it is in the basement—and it’s not even my office; I share it.

I am not beyond self-deprecation or blind to the realities of my broader profession. There is nothing wrong with the seat I occupy. It is precisely where I dreamt of being when I took my first college-level history course in 2001—A 2001 History Odyssey, if you will! (said my best American Dream Dusty Rhodes impression) By the way, who has ever been unsatisfied with a dream coming true?

In that History Pedagogy course, newly hired as a tenure-track professor, I stood on the border, a fork in the road between the scholarly and the mainstream worlds. And in that space, I discovered something surprising: perhaps my role wasn’t to choose a side but to bridge the divide between them.

This endeavor isn’t about fame or recognition. I’ve never aspired to be a household name or to seek the spotlight. My goal is more straightforward yet profoundly important: to share what I’ve learned and to carry the richness of academic scholarship beyond the university and into the public sphere. What good is knowledge if it remains locked away, accessible only to those with the credentials to enter?

In many ways, this paper (no, this X article!) is the product of that reflection. It partly reflects my inner dialogue in 2021, adding my more modern sensibility, which I have earned through my experience of cultural shifts in the last four years. It challenges the notion that knowledge is the exclusive property of the Academy and asks complex questions: Who gets to be a historian? Where is knowledge created?

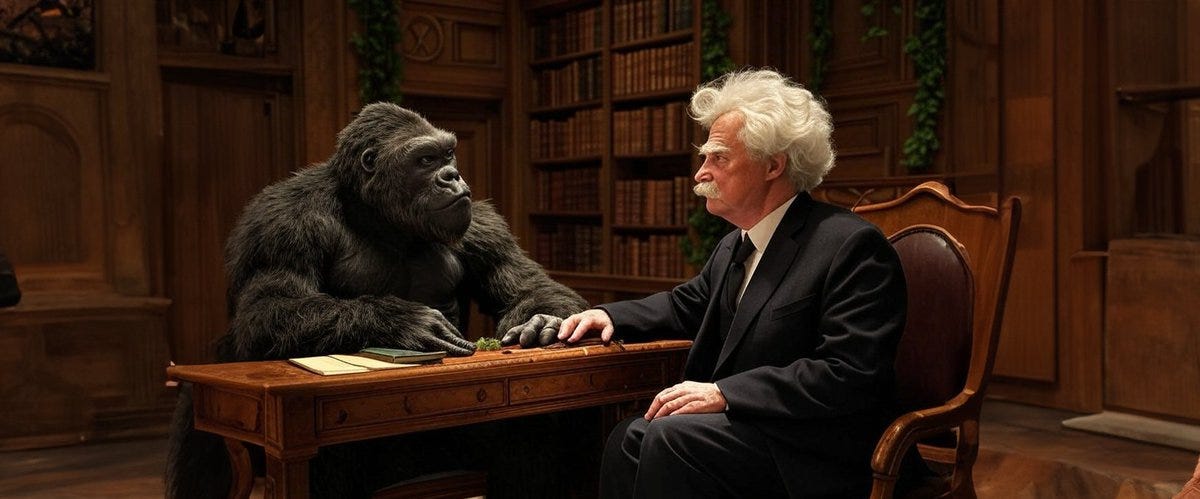

I like to think of myself as a California historian in the spirit of those who came before me, chronicling the story of a land that has always defied easy definition. My favorite historians of 19th-century California are an eclectic lot: Father Juan Crespí, Hubert Howe Bancroft, Major Horace Bell, Harris Newmark, and a handful of others—including Mark Twain. They all share a common thread that speaks to something quintessentially American.

For all his towering legacy in the history of the American West, Bancroft never attended formal schooling beyond the age of sixteen. His name adorns the most prestigious library in California, the Bancroft Library, at UC Berkeley. Crespí, a Franciscan missionary, was perhaps the most formally educated, his mind shaped by the disciplined rigor of the seminary. Newmark’s education was modest, pieced together in Kentucky before he found himself amidst the raw, unfolding drama of Los Angeles. Then there’s Major Bell—a soldier, adventurer, and storyteller who captured the spirit of frontier California with the flair of a man who lived it.

Thinking about them, I couldn’t help but wonder: Have our best historians always been, particularly in the American West, the common man? It seems so. Unlike the Old World, where history was often the province of scholars in cloistered libraries, the West was chronicled by those who built it, fought for it, and survived it. They weren’t just observers but participants, scribbling their accounts with ink still wet from the blood of life.

Perhaps that’s the true legacy of American cultural history—not just in the West but across the nation. Our historians have often been farmers, soldiers, merchants, missionaries, and people who picked up a pen not because it was their profession but because they felt the story needed to be told. And in doing so, they shaped not just the record of history but the very soul of it.

Perhaps most importantly, how do we redefine the role of the historian in a world where history is told not just in the classroom, fancy books, or academic journals but also in social media posts, podcasts, and viral videos? I do not claim to have the answers, but the questions are worth asking. In asking them, we might find a new path forward—not one that diminishes the value of academic rigor but one that ensures history belongs to everyone.

SOURCES | BIBLIOGRAPHY

You won't see this in those "mainstream" sources... in the order of appearance since X does not currently have footnotes:

Wineburg, Sam. Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone). p. 52.