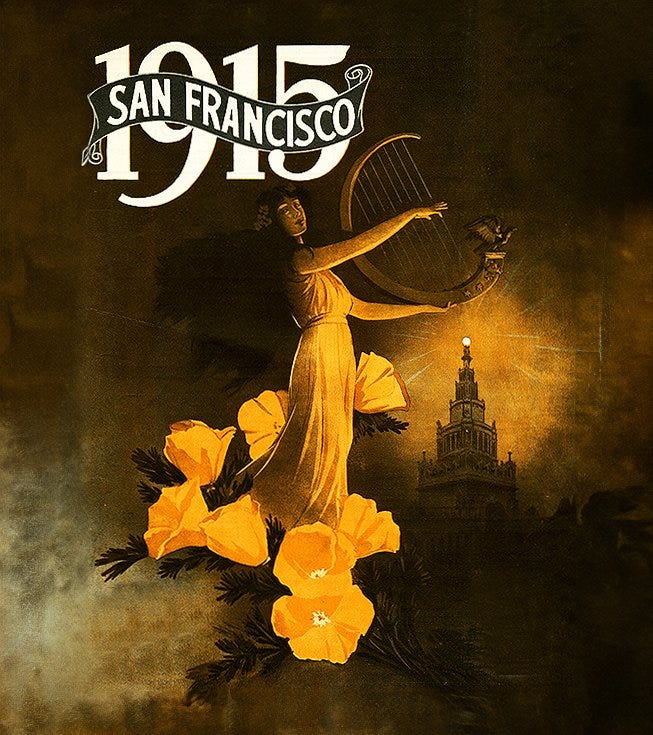

In the tender spring of 1915, as the world beyond the Golden Gate shuddered under the first salvos of a great and terrible war, San Francisco flung open the gates of a spectacle so bold and luminous that it seemed to defy the gathering darkness. The Panama-Pacific International Exposition, sprawled across 635 acres of reclaimed marshland along the city’s waterfront, was no mere fairground frolic—it was a hymn to human daring, a testament to a people who had stared into the abyss of ruin and emerged with a dream.

Born to celebrate two monumental feats—the discovery of the Pacific by Vasco Núñez de Balboa four centuries earlier and the piercing of the Panama isthmus by a canal that wedded oceans—it rose from a city still scarred by the earthquake of 1906, a phoenix of plaster and steel poised to dazzle the nations. From February 20 to December 4, across ten months of splendor, nearly twenty million souls would pass through its portals, their eyes lifted to the Tower of Jewels, their hearts stirred by a vision of progress that shimmered like the bay itself. Here was San Francisco’s moment, a stage where the past whispered to the future, and a people, tempered by trial, claimed their place in the sweep of history.

The seed of this grand endeavor had been planted long before, in 1904, when Reuben Hale, a merchant with a dreamer’s soul, first mused on a world’s fair to herald the Panama Canal’s nearing completion. It was a quiet notion then, a flicker in a man's mind who saw beyond the daily grind of commerce to a celebration that might bind nations. But fate dealt a cruel hand two years later, on April 18, 1906, when the earth convulsed beneath San Francisco, toppling its towers and torching its dreams.

The Great Earthquake left a city in ashes—three-quarters of its structures gone, its people reeling—yet from that smoldering wreckage emerged a resolve as unyielding as the bedrock beneath. By 1909, as the scars began to heal, San Francisco’s leaders turned their gaze again to Hale’s vision, determined to rebuild and transcend. They would show the world their recovery, bury the quake’s devastation beneath a monument of progress, and stake their claim as a gateway to the Pacific.

The path to that triumph was no gentle stroll—it was a contest of wills, a duel fought with dollars and determination against a rival suitor far to the south. New Orleans, perched near the canal’s Atlantic mouth, had its designs, sending a “deputation” to Washington to plead its case. San Francisco answered with a ferocity born of necessity. On April 18, 1910—the fourth anniversary of the earthquake—the city’s citizens gathered in a special fund-raising fervor, purchasing over $4 million in exposition bonds, a fortune amassed by the will of a people unbowed. The city government matched their zeal, appropriating $5 million, while the California state legislature pledged another $5 million—a staggering $10 million war chest that dwarfed New Orleans’ bid.

In Washington, Charles C. Moore, a steady hand at the helm, led a delegation to sway Congress, their voices ringing with the promise of a Western metropolis reborn. Forty-two subscribers, civic titans, had laid the financial cornerstone with their own $4 million stake. On February 15, 1911, President William Howard Taft lent his signature to their cause, signing the Joint Resolution that crowned San Francisco the exposition city. New Orleans faded into shadow, its challenge a whisper against the roar of a city that refused to be forgotten.

Construction began that same year, a labor as monumental as the canal it sought to honor. Taft himself journeyed west to break ground at Golden Gate Park, a ceremonial shovel turning earth in a gesture of federal faith. The site soon shifted to Harbor View, a muddy tidal flat wrested from the bay’s grasp, where nearly $50 million—$17.5 million from city and state, the rest from concessionaires and exhibitors—would transform 635 acres into a city of delight. Winifred Black, writing as “Annie Laurie,” captured its nascent allure: “You could see it all—the sullen blue-green of the Presidio forest... the silver of the gleaming bay... the purple majesty of the far mountains... and the tender green of the Marin hills.”

By February 20, 1915, the gates swung wide, revealing a rectangular marvel of ten exhibit halls encircling courtyards, crowned at its western end by the Palace of Fine Arts, where Monet and Van Gogh’s canvases whispered of beauty eternal. At its heart stood the Tower of Jewels, forty-three stories high, its exterior ablaze with over $100,000 in glass beads—strung on wires, swaying in the breeze, tiny mirrors amplifying their shimmer. It was a beacon of optimism, a proclamation that humanity could craft something sublime even amidst war’s shadow.

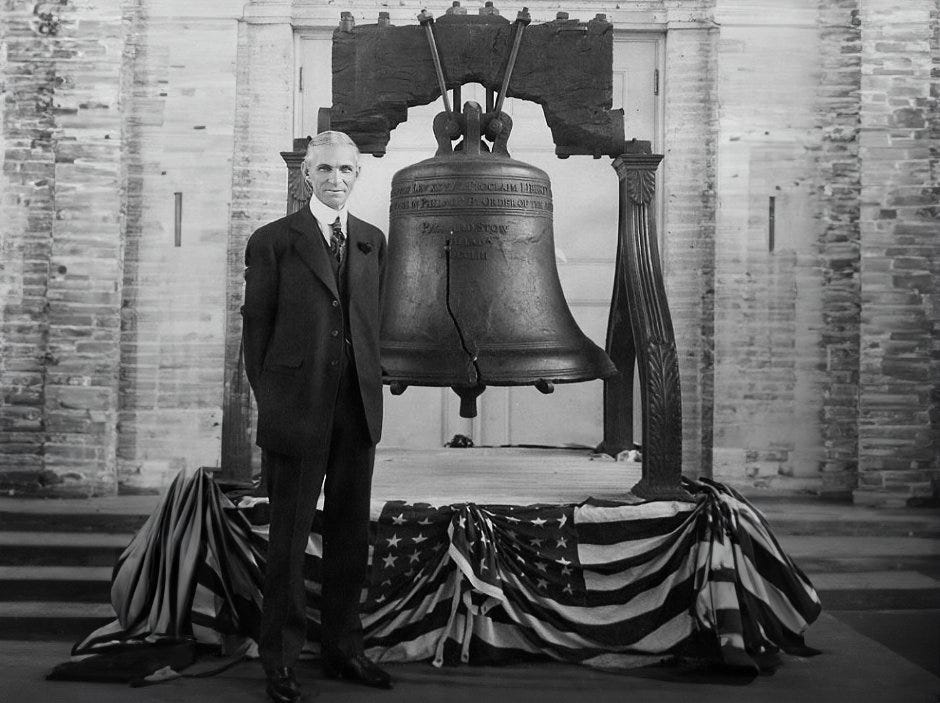

The exposition was a kaleidoscope of wonders, a microcosm of the age’s ingenuity and ambition. Visitors marveled as Levi’s jeans took shape before their eyes or watched a Ford Model T roll off a working assembly line, eighteen cars birthed each afternoon in a dance of modern industry. Henry Ford himself, joined by Thomas Edison and Harvey Firestone—those titans of the road dubbed the “Vagabonds”—trekked 3,500 miles from Detroit to San Francisco, their Model Ts carving a path that popularized the automobile’s promise.

On October 29, they rolled into the Plaza de Panama, greeted by thousands of schoolchildren showering them with flowers, a moment of joy amid their pilgrimage. Edison, feted on his day, walked the grounds where his genius found echo, while Ford’s exhibit showcased a revolution—cars tumbling from the line at prices that dropped from $850 in 1908 to $300 by 1924, a marvel that made the open road a birthright for the common man.

The skies, too, bore witness to daring. Art Smith, the “boy aviator,” looped and soared, his plane trailing fireworks like a comet against the night, a successor to Lincoln Beachey, the “king of the skies,” whose loop-the-loop ended in a fatal plunge into the bay. For ten dollars, ordinary souls could ascend with the Loughead brothers—later Lockheed—in planes that swept over the fair and the bay, offering a god’s-eye view of the spectacle below. And then there was Harry Houdini, the self-liberator, who slipped into the tale late in its run.

On November 6, 1915, he let himself be locked in a heavy wooden box, roped and lowered into the bay, only to surface in less than thirty seconds, swimming to a barge as cameras rolled. The next day, he dazzled 2,300 San Quentin prisoners, his tricks teasing men who knew confinement’s weight, though none, the San Francisco Examiner mused, pierced his secrets. Yet, in the exhaustive ledger of “The Story of the Exposition,” Houdini’s name finds no echo—a fleeting marvel unclaimed by its official chronicle.

The SF Examiner wrote on November 8, 1915: “Houdini throws the big thrills into this week’s show at the Orpheum… His new act surpasses all the previous ones… At the Exposition last Saturday [Nov. 6, 1915], Houdini permitted himself to be locked in a heavy wooden box which was then roped and lowered into the bay. Less than a half minute later he appeared at the surface of the water and swam to the waiting barge. This entire scene was filmed, and the motion picture incorporated in the act, will be shown throughout the country.... Although to the general public it might seem unwise to have the celebrated ‘self-liberator’ exhibit his skill to an audience that might be especially interested in his tricks, Houdini performed for the 2,300 prisoners in San Quentin yesterday afternoon… If nobody in the penitentiary learned any more of the modus operandi than was apparent to the Orpheum patrons…the only result, however, must have been to make some of the San Quentin spectators envious of his peculiar accomplishments.”

The fair was a tapestry of the whimsical and the profound. Visitors rode a six-acre replica of the Grand Canyon or marveled at a five-acre model of the Panama Canal, its locks and waters a miniature of the triumph it celebrated. They ascended nearly three hundred feet in a “house” tethered to a steel arm or gazed at a temple molded from soap, a rosebush of gems, a sculpture of butter.

Former President Theodore Roosevelt addressed the throng with a thunderclap, hailing the exposition as a monument to American vigor. At the same time, Vice President Thomas Marshall dedicated it with words that lingered: “A people dies when it loses its vision.” John Philip Sousa’s band set feet tapping with martial strains, and Ignace Paderewski’s piano sang of distant lands. Twenty-nine states raised pavilions, and though World War I pruned foreign ranks, twenty-five nations still sent their treasures—paintings, machines, dreams.

The cost was staggering—nearly $50 million, roughly $1.5 billion—yet the return was beyond measure. Almost twenty million visitors visited the Panama Pacific International Exposition, one of the era’s most successful expositions, each witnessing a city’s defiance. The preface of “The Story of the Exposition” dared to claim it a “microcosm so nearly complete” that, were the world beyond its gates to perish, civilization might be reborn from its 635 acres. It was a bold boast, tempered by war’s reality, yet for those ten months, it held. The Civic Auditorium and Palace of Fine Arts endured, sentinels of memory, while the rest succumbed to time—torn down for shops and homes. On December 4, 1915, the gates closed, the lights dimmed, and the Tower of Jewels fell silent, its beads stilled by a breeze that carried the echoes of a fleeting utopia.

This was no mere carnival—San Francisco’s soul lay bare, a city that had wrestled ruin and emerged not just standing, but soaring. The exposition drew the era’s giants—Ford and Edison reshaping industry, Roosevelt and Taft lending gravitas, Houdini defying locks, and Sousa and Paderewski stirring hearts. It birthed a legacy of motion, as Ford’s Model Ts and the Loughead brothers’ flights heralded an America unbound by rails or rivers. The automobile, that clattering herald of modernity, found its prophet in Ford, whose assembly line—demonstrated daily—slashed prices and swelled the nation’s roads. This revolution by 1929 saw three million cars humming across the land, two million in California alone. Suburbs bloomed, oil flowed, and cities like Los Angeles swelled—its population doubling in a decade, its streets widened to tame the tide.

Yet beneath the triumph lay shadows. The war that pruned foreign pavilions cast a pall, a reminder of fragility beyond the bay. For all its promise, the automobile's rise would reshape America in ways unforeseen—decentralizing cities, choking streets, and birthing a thirst for oil that would one day rival the canal’s might. The exposition was a dream of the possible, a moment when San Francisco, with grit and grace, held a mirror to the nation’s soul. Ultimately, it was a fleeting White City of the West, a counterpart to Chicago’s 1893 marvel, where optimism danced with reality, and a people, rising from ashes, dared to write their name across the sky.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Todd, Frank Morton. The Story of the Exposition; Being the Official History of the International Celebration Held at San Francisco in 1915 to Commemorate the Discovery of the Pacific Ocean and the Construction of the Panama Canal. 5 vols. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons / The Knickerbocker Press, 1921.

Ackley, Laura. “An Introduction to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition.” PPIE100, January 23, 2015.

Moore, Alison. “Adventures of the ‘Vagabonds.’” PPIE100, July 14, 2015.

Nolte, Carl. “Panama-Pacific Fair Changed San Francisco Forever.” San Francisco Chronicle, [n.d.].

PBS. “The Panama Pacific International Exposition.” American Experience, [n.d.].

Samuel, Lawrence R. End of the Innocence: The 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2010.