The end of the Civil War left the American South in devastation—its cities smoldering, its economy shattered, and its social order turned upside down. Fields once worked by enslaved labor lay fallow, railroads lay in twisted ruin, and the once-powerful planter class was stripped of wealth and certainty by the Civil War.

In Washington, the federal government faced the towering challenge of reunification. How would the former Confederate states be brought back into the Union? More pressing still, what would freedom mean for the four million men, women, and children who had been enslaved? The promise of Reconstruction was clear: to rebuild not just the South but the very idea of the American Republic, ensuring that liberty belonged to all.

Reconstruction would be a period of bold ambition and fierce resistance. Every step toward racial equality—Black suffrage, civil rights protections, the election of Black officials—met with opposition from those who sought to restore the old order. Progress was real, but so, too, were the political and judicial setbacks that undermined it. Laws were passed, then challenged. Rights were granted, then contested. The struggle for freedom had not ended with the war; in many ways, it had just begun.

Though the end of slavery was written into law, it was never merely about legal emancipation. It was about something far more personal and profound: reuniting families, securing economic independence, and claiming the full rights of citizenship. For the newly freed, freedom was not an abstract principle but a tangible pursuit, one that often began with the search for loved ones torn away by the machinery of slavery.

Men and women walked miles, sometimes across entire states, searching for sons, daughters, husbands, and wives who had been sold away. Black newspapers became a lifeline, carrying advertisements placed by those desperate to find missing kin: “Information wanted of my mother…” one might begin, the plea printed in columns that ran week after week. The Freedmen’s Bureau, established by Congress to aid in the transition from slavery to freedom, worked tirelessly—though often with too few resources—to help reunite families.

Among the most significant yet often overlooked victories of this era was the formal recognition of Black marriages, once disregarded under slavery. For many, legalizing their unions was more than a bureaucratic procedure; it was a declaration of dignity and personhood. It was the first time the nation recognized their commitments to each other, having, for centuries, refused to see them as husbands and wives.

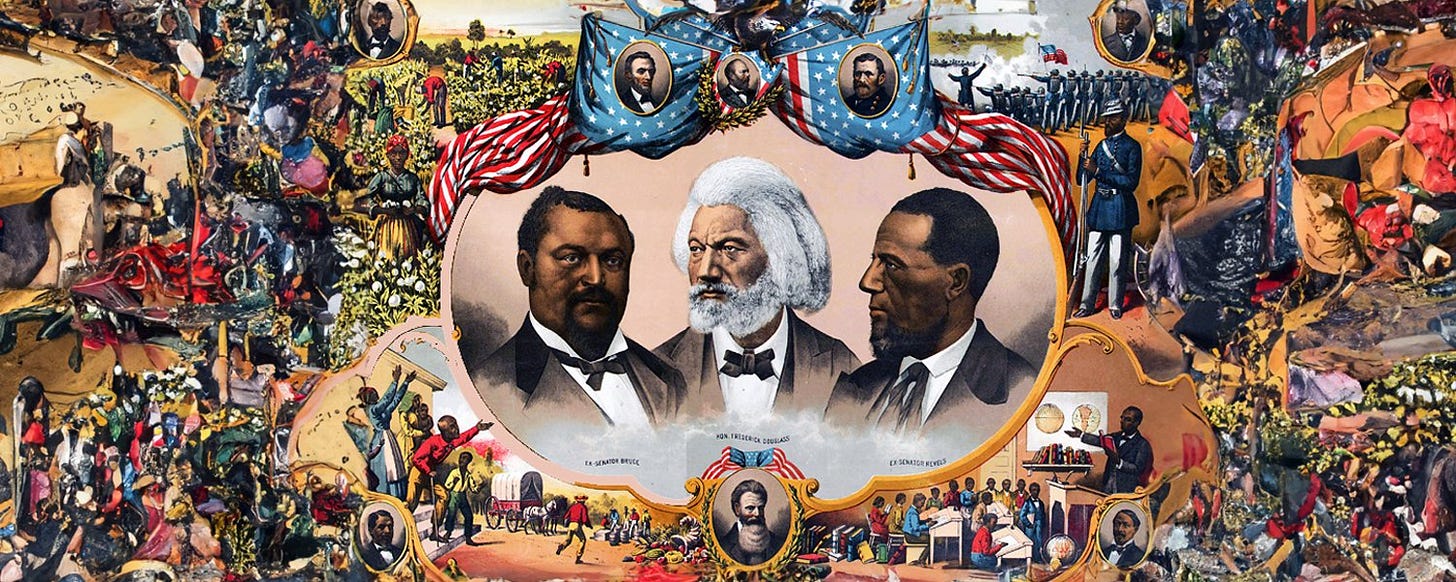

The Reconstruction years saw an explosion of Black political participation. With the passage of the 15th Amendment, African Americans voted in large numbers and held public office in towns and cities across the South. They were elected as sheriffs, legislators, and, in a remarkable turn, to the halls of Congress itself.

John Roy Lynch of Mississippi was one such leader. Born enslaved, he rose to prominence as a legislator and later a U.S. Congressman. In a speech before Congress, he recounted the humiliations he endured while simply trying to travel north, forced to sit in segregated cars, subjected to indignities that made clear that political rights alone would not bring full equality. Still, he and others pressed forward, determined to build a society where Black Americans could claim freedom and full citizenship.

The bold and ambitious experiment of the Freedmen’s Bureau worked to provide economic, legal, and educational support to the formerly enslaved. Yet, burdened by limited funds and resistance from white Southerners, its reach fell short of its mission. Still, in the years immediately following the Civil War, the Bureau played a crucial role in establishing schools and providing a foundation for Black communities eager to chart their own futures.

For freed people, literacy was more than a practical tool—it was an assertion of self-worth, a rejection of the old order that had sought to keep them ignorant. Schools became symbols of progress, but they were also battlegrounds. White supremacists, fearful of the power that education could bring, attacked Black schools and teachers, determined to suppress this newfound pursuit of knowledge. Yet, the hunger for learning could not be so easily extinguished. Freedmen’s schools, many founded by Northern missionaries and Black educators alike, continued to grow.

This commitment to education was central to African American aspirations during Reconstruction. Learning to read and write—to place one’s own name on a piece of paper—was, in its way, as radical an act as casting a ballot. It was a declaration of literacy and belonging to the American polity, history, and citizenry—a sense of belonging to the American Republic in a way that had not existed before the Civil War.

Reconstruction was a moment of possibility and breathtaking ambition. It was also a moment of resistance, a reminder that freedom, once proclaimed, must still be defended. The struggle to reunite families, build communities, and claim citizenship rights was not a footnote to the Civil War—it was the next great chapter in the American story.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blight, David. "Lecture 20: Wartime Reconstruction: Imagining the Aftermath and a Second American Republic." Yale University, 2008.

Blight, David. "Lecture 24: Retreat from Reconstruction: The Grant Era and Paths to 'Southern Redemption.'" Yale University, 2008.

Blight, David. "Lecture 25: The 'End' of Reconstruction: Disputed Election of 1876, and the 'Compromise of 1877.'" Yale University, 2008.

OpenStax. "U.S. History." OpenStax, 2016.

The American Yawp. "The Reconstruction Era (1865–1877)." Stanford University Press, 2022.

Teaching American History. "Documents on Reconstruction." Ashbrook Center, Ashland University, 2023.

Digital History. "Reconstruction (1865–1877)." University of Houston, 2023.

Britannica. "Reconstruction."

Schweikart, Larry, and Michael Allen. A Patriot's History of the United States: From Columbus's Great Discovery to the War on Terror. New York: Sentinel, 2004.

Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. New York: Harper & Row, 1980.