Even before the Civil War ended, President Abraham Lincoln began shaping his vision for reunifying the shattered nation. His Ten Percent Plan, introduced in 1863, sought a swift and lenient restoration of the Southern states. If just ten percent of a state's 1860 voters pledged allegiance to the Union, they could form a new government and rejoin the nation. Lincoln prioritized reconciliation over punishment, hoping to bring the South back into the fold with minimal resistance.

However, not everyone in Washington shared this vision. Many in Congress, particularly the Radical Republicans, believed that a mere loyalty oath was insufficient. They sought a more transformative Reconstruction that would fundamentally remake the South. Their plan called for full civil rights for freed people, sweeping economic reforms, and a restructured society based on free labor rather than racial hierarchy. To them, anything less betrayed the sacrifices made during the war.

The course of Reconstruction (which started in 1863) shifted dramatically after Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865. Andrew Johnson, Lincoln's successor, was a man of contradictions—a Southern Democrat who had remained loyal to the Union, yet deeply resistant to racial equality. Johnson’s policies made the reintegration of former Confederate states remarkably easy, allowing many of the same elites who had led the rebellion to regain power quickly.

Johnson was a man wedded to a hierarchical vision of society, one in which legal emancipation did not mean true racial equality. Johnson vetoed civil rights bills designed to protect freedmen, insisting that federal interference in state affairs was unconstitutional. He pardoned Confederate leaders, allowing them to resume political office, and opposed efforts to provide land or economic aid to formerly enslaved people. Meanwhile, the South was in chaos.

Freedmen—many displaced by war—wandered train depots and country roads searching for work and family members. Across the region, white state governments passed Black Codes, laws that restricted Black labor, movement, and political participation. As resistance to federal authority mounted, it became clear that more drastic measures would be needed to secure the promises of Reconstruction.

In 1867, Congress, now firmly under Radical Republican control, responded to Johnson’s obstruction by passing the Military Reconstruction Act, one of American history's most sweeping federal policies. This law divided ten Southern states into five military districts, each under the command of a Union general.

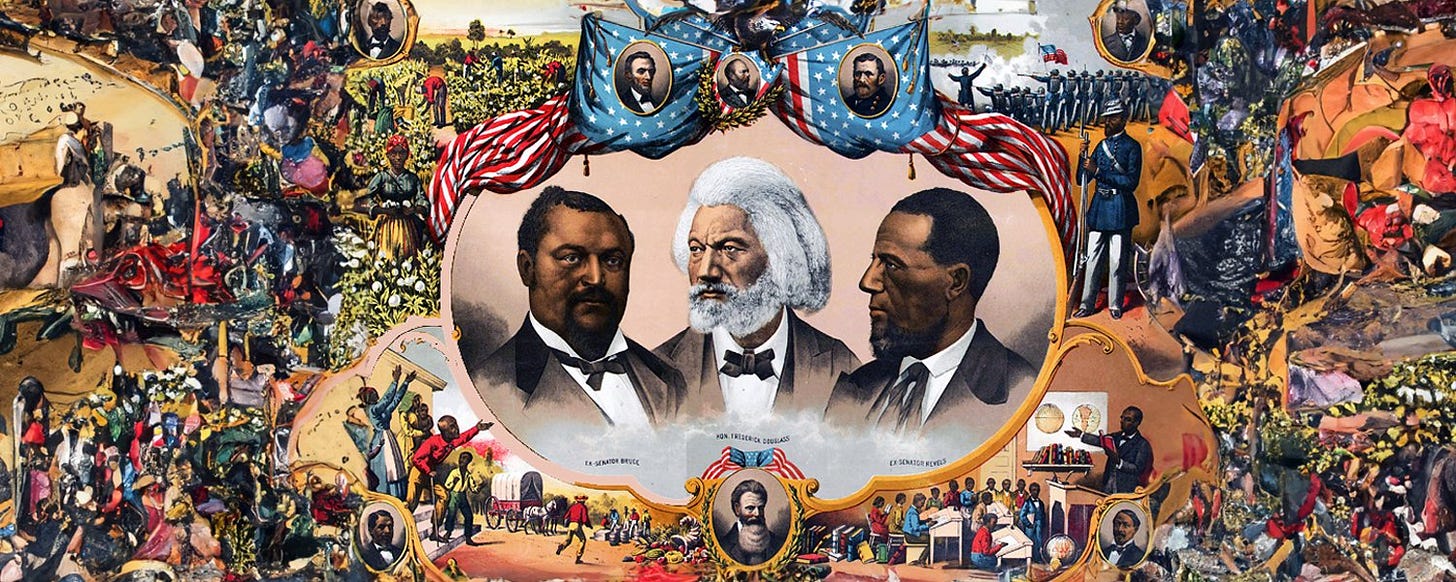

Martial law was imposed, and new state constitutions guaranteeing equal rights for Black citizens were required before any state could be readmitted to the Union. Federal troops were deployed to protect freedmen and oversee elections. For a time, it worked. Black political participation surged. Freedmen largely voted, won local and state elections, and even sent representatives to Congress. This was a moment of remarkable possibility—America’s first experiment in genuine interracial democracy.

However, as Black political and economic power grew, so did white resistance. Violence became a primary weapon in the effort to undo Reconstruction. The Colfax Massacre of 1873 was one of the most brutal episodes of this era. White militias, angered by a contested election in Louisiana, attacked Black Republicans defending a courthouse. By the end of the assault, over 150 African Americans lay dead.

The federal government attempted to respond, but the Supreme Court’s ruling in United States v. Cruikshank (1876) effectively nullified federal prosecution of racial violence. The decision gutted the 14th Amendment, ruling that it restricted only state action—not the acts of private individuals. This, along with the Slaughterhouse Cases (1873, the decision came the day after the Colfax Massacre), severely weakened the federal government’s ability to protect Black citizens from terror and discrimination. These rulings were “the legal cementing of Redemption”—a signal that the federal government was retreating from the ambitious goals of Reconstruction.

By 1876, Reconstruction was already faltering. The North had grown weary of the long, bitter struggle over the South, and the Republican Party itself was shifting its focus away from racial justice. That year, the presidential election between Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel Tilden ended in controversy. The nation faced a political crisis, with electoral votes disputed in several Southern states.

The resolution came as a backroom deal: the Compromise of 1877. In exchange for securing Hayes’s presidency, Republicans agreed to withdraw federal troops from the South, signaling that the federal government would no longer enforce Reconstruction. Blight calls this compromise “the final nail in the coffin of Reconstruction.” With the military gone, white Democrats—who called themselves “Redeemers”—moved swiftly to dismantle Black political and economic gains.

What followed was the rapid establishment of Jim Crow laws, which would enforce racial segregation and disenfranchise Black voters for nearly a century. Frederick Douglass had seen it coming. In 1875, he warned that “peace among the whites” would come at the cost of justice for Black Americans. And so it did.

Although Reconstruction ended in 1877, its impact reverberated throughout the following century. It laid the constitutional groundwork for the Civil Rights Movement of the 20th century and demonstrated the limits of federal intervention in racial justice. Black leaders like Booker T. Washington urged African Americans to focus on education, property ownership, and economic advancement. Others, like John Hope, rejected gradualism and declared, “If we are not striving for equality, in heaven’s name for what are we living?”

Northern philanthropists, including Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, helped fund Black schools, but the reality remained grim. Most Black Southerners were trapped in an economy designed to keep them subordinate and dependent. Blight frames Reconstruction as “a revolution interrupted”—a moment when America had the chance to create a true Republic, only to retreat under the weight of racism and political expediency. The Civil War had birthed a new American republic, but the Reconstruction era proved just how deeply contested that republic would remain.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blight, David. "Lecture 20: Wartime Reconstruction: Imagining the Aftermath and a Second American Republic." Yale University, 2008.

Blight, David. "Lecture 24: Retreat from Reconstruction: The Grant Era and Paths to 'Southern Redemption.'" Yale University, 2008.

Blight, David. "Lecture 25: The 'End' of Reconstruction: Disputed Election of 1876, and the 'Compromise of 1877.'" Yale University, 2008.

OpenStax. "U.S. History." OpenStax, 2016.

The American Yawp. "The Reconstruction Era (1865–1877)." Stanford University Press, 2022.

Teaching American History. "Documents on Reconstruction." Ashbrook Center, Ashland University, 2023.

Digital History. "Reconstruction (1865–1877)." University of Houston, 2023.

Britannica. "Reconstruction."

Schweikart, Larry, and Michael Allen. A Patriot's History of the United States: From Columbus's Great Discovery to the War on Terror. New York: Sentinel, 2004.

Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. New York: Harper & Row, 1980.