Rivers, Material, and Speech: The Luiseño-Cahuilla in Southern California’s

Chapter 2

The Luiseño-Cahuilla: A Southern Shoshonean Mosaic

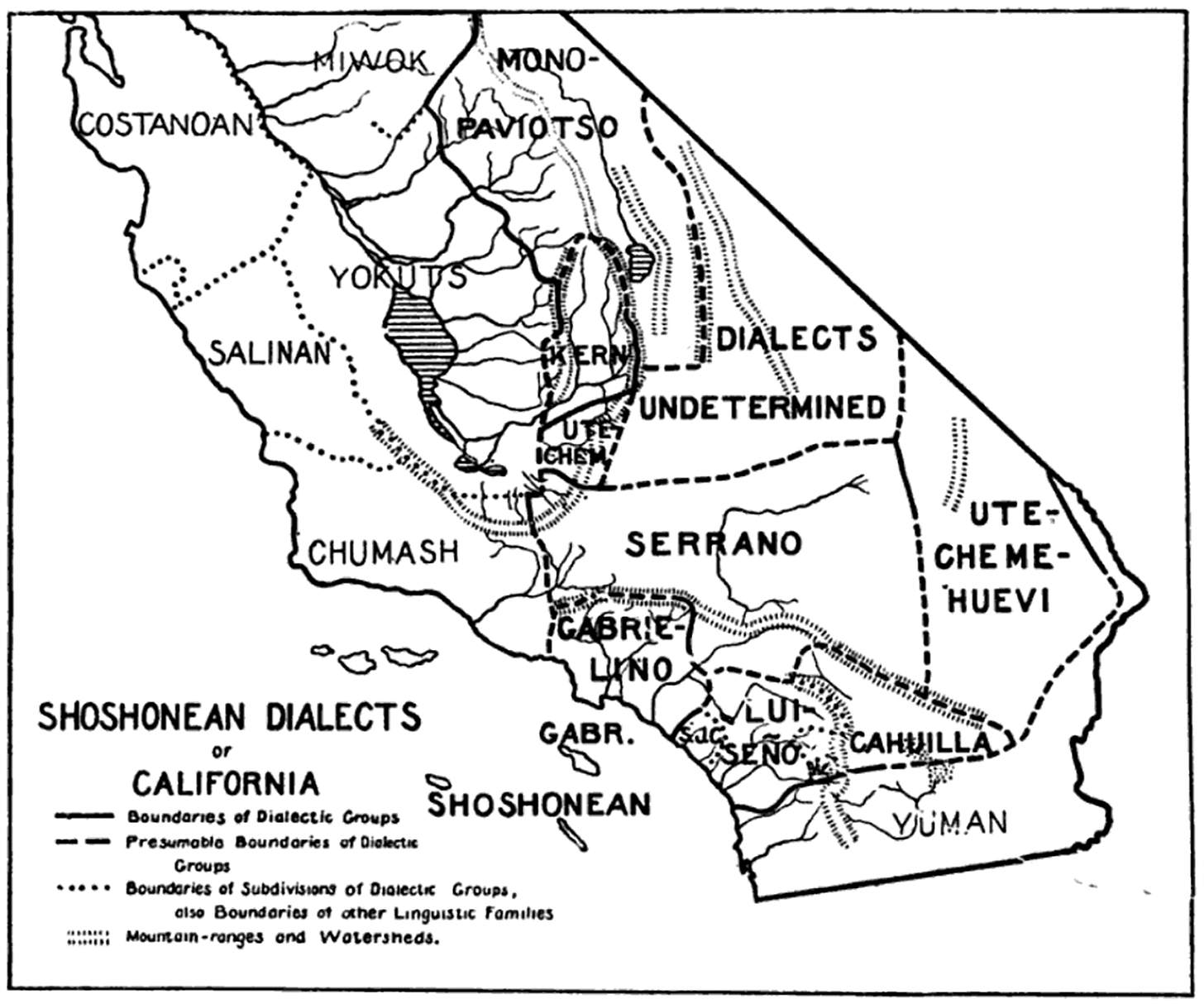

The Luiseño-Cahuilla inhabited a region south of the Serrano to the northeast and the Gabrielino to the northwest. Unlike their more dialectically uniform neighbors, the Luiseño-Cahuilla were a diverse constellation of at least four subdivisions—Luiseño, Cahuilla, Agua Caliente, and San Juan Capistrano (or Juaneño)—each bound by shared Shoshonean roots yet shaped by the nuances of their local landscapes.

The Luiseño-Cahuilla group was not a monolith, but a vibrant mosaic of peoples, their identities tied to place and language, though the Luiseño and Cahuilla formed the numerical heart of the group. The Agua Caliente, geographically and linguistically a bridge between the two, occupied the headwaters of rivers like the San Luis Rey, their lives blending traits of both neighbors.

The San Juan Capistrano, or Juaneño, leaned closest to the Luiseño in dialect and culture, perhaps serving as a subtle transition to the Gabrielino farther north. Together, these subdivisions formed a network of communities, each distinct yet united by a shared Shoshonean heritage; their differences were as much a product of the land as of their language. I was once told by a great scholar/historian, USC Professor Phil Ethington, who found in his research for his book Clovis to Nixon, that to develop a distinct dialect, it took at least three hundred years without conversation—to me, this shows the isolation of tribes in California to have 300 dialects and roughly 80 to 90 distinct languages (some sourcs list this number at ~130).

The Luiseño: People of the San Luis Rey

The Luiseño, the most prominent of the group, called themselves Ghecham or Khecham, a name tied to the San Luis Rey Mission and possibly rooted in kicha, meaning “house” in their tongue. Their language, cham-tela or “our speech,” was less a formal name than a declaration of identity, akin to the “Netela” of their Juaneño kin.

Suggestions that names like Khecham or Gaitchim (linked to San Onofre) were true tribal designations remain uncertain, perhaps reflecting local places rather than broader ethnic labels. What is clear is the Luiseño’s deep connection to their territory, a domain centered on the San Luis Rey River’s drainage, save for its headwaters held by the Agua Caliente and the Yuman-speaking Diegueño. This territory stretched across a vibrant swath of Southern California, from the coastal plains near Agua Hedionda, San Marcos, Escondido, and Valley Center to the interior reaches of Temecula, Santa Rosa, Aguanga, Pauba, and Elsinore Lake.

On the coast, Luiseño lands extended north to Las Flores, just shy of San Onofre, which belonged to the Juaneño. Inland, the village of Saboba at San Jacinto marked a linguistic outlier, its people called Sovovoyam by the southern Luiseño. The Luiseño’s reach stopped short of the San Jacinto divide, where Cahuilla, Serrano, or Diegueño held sway over the upper waters of the San Luis Rey and Santa Margarita rivers, and the San Gorgonio Mountains. Temescal Creek, flowing from Elsinore Lake, was a shared frontier with the Gabrielino, a reminder of the fluid boundaries that defined Native Southern California.

South of their core territory, the Diegueño held Batiquitos, Encinitas, San Dieguito, San Bernardo, San Pasqual, Guejito, and Mesa Grande, their Yuman tongue marking a cultural divide. Up the San Luis Rey River, Luiseño villages like Puerta Noria and Puerta de la Cruz gave way to Diegueño settlements at San José. The Cahuilla, meanwhile, claimed the headwaters of the Santa Margarita River, with their reservation serving as a stronghold in the region’s interior. The San Gorgonio Mountains, towering to the north, were a shared domain of Cahuilla and Serrano, their rugged slopes a testament to the region’s complex human geography.

This was a landscape of movement and exchange, where the Luiseño-Cahuilla navigated a web of neighbors—Chumash to the west with their tomol canoes, Serrano in the high deserts, and Gabrielino along the northern coasts. Their villages, ranging from small hamlets to larger settlements like Saboba, were hubs of activity, where chieftains mediated disputes and shamans wielded spiritual authority. The Luiseño-Cahuilla’s material culture—baskets of coiled grass, bows of willow and ash, aprons of dogbane twine—reflected their mastery of local resources, while their languages and dialects spoke to a deeper unity. In this southern corner of California, they crafted a way of life that balanced diversity with cohesion, their communities as enduring as the rivers and mountains that shaped them.

Luiseño Material Culture: Clothing

Luiseño clothing was a study in minimalism, shaped by the region’s mild climate and occasional biting cold. Men often went without clothing in warmer months, their bodies unencumbered under the Southern California sun. In colder seasons, they donned cape-like garments that draped from their shoulders to their knees, crafted from rabbit skins sliced into strips and woven with twine, or fashioned from deer or sea-otter pelts. The latter, prized for their sheen and warmth, were rare treasures, likely reserved for coastal communities with access to marine resources.

Women, by contrast, never went unclothed. They wore aprons—pishkwut, a delicate network of dogbane or milkweed twine, worn in front, and shehevish, woven from the soft inner bark of willow or cottonwood, worn behind. These aprons were both practical and modest, a cultural insistence on coverage regardless of season. Headwear, too, served dual purposes. Women wore basket hats of tightly coiled grass, which doubled as padding under the strain of carrying nets laden with acorns or cactus.

Men occasionally adopted these hats for similar tasks, their conical forms shielding the forehead from the weight of burdens. Another head covering, woven from rushes, offered similar utility, a testament to the Luiseño’s knack for turning local flora into everyday life tools. These artifacts, simple yet purposeful, reveal a people attuned to the rhythms of their environment, crafting what they needed from the materials at hand.

Luiseño Material Culture: Baskets

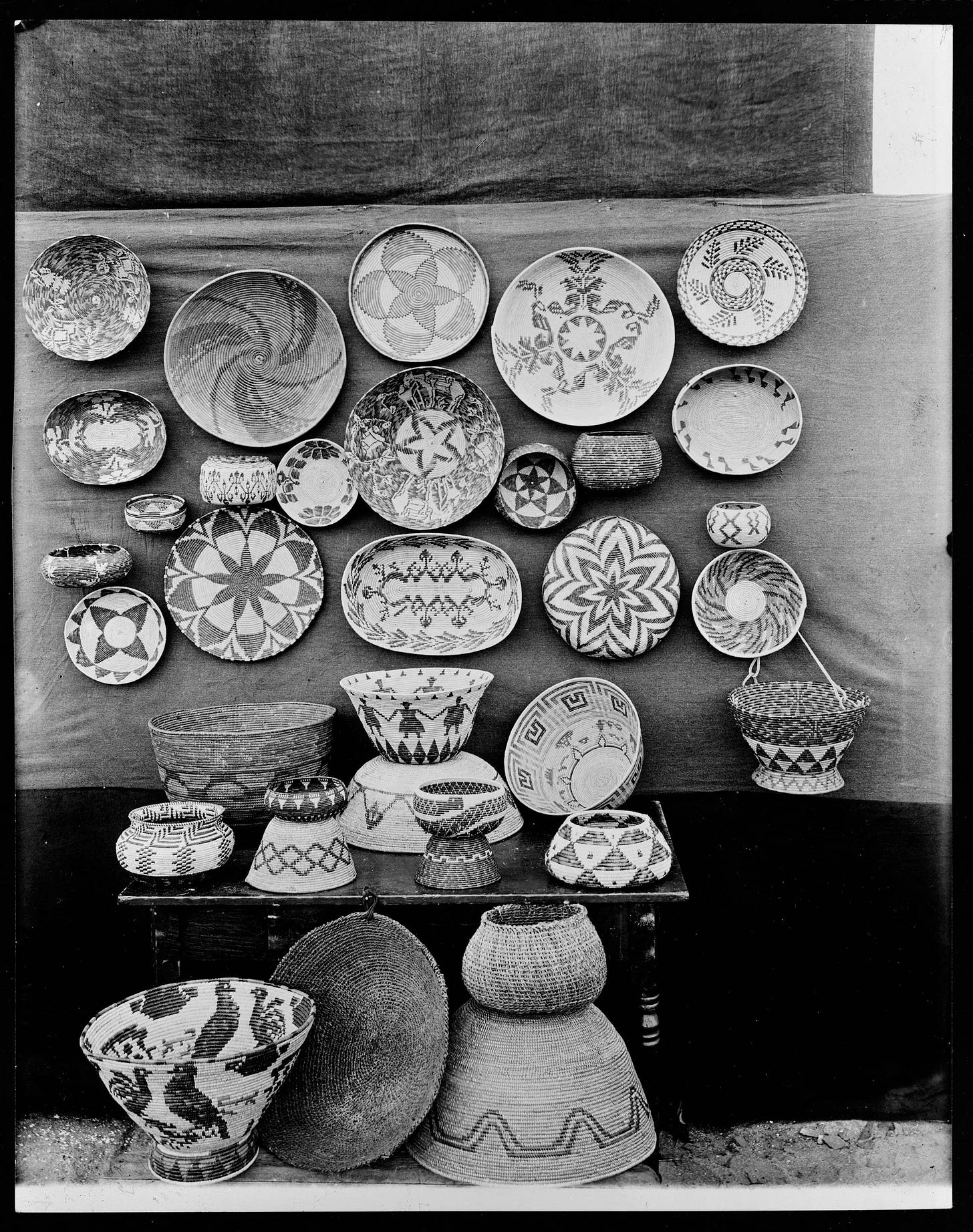

Basketry was the Luiseño’s great art, a craft where utility met aesthetic precision. Their coiled baskets, built on a foundation of Epicampes rigens grass and wrapped with splints of aromatic sumac or rush, were marvels of patience and skill. Each basket was unique, its black or brown patterns—never guided by a model—emerging from the maker’s fleeting inspiration. Claims of hidden symbolism in these designs, often romanticized by outsiders, find no echo in Luiseño tradition; the patterns were purely artistic, reflecting individual creativity rather than a religious code.

The baskets served myriad purposes, each form tailored to a specific task. The chilkwut, a conical basket, doubled as a hat, drinking vessel, or even a bowl for meals. The peyevla, a large storage basket, held acorns, seeds, and other staples, its sturdy coils safeguarding the community’s sustenance. The tukmal, nearly flat, was a winnowing tool, its contents lifted to the breeze to separate grain from chaff. The pa’kwut, a basin-shaped workhorse, came in various sizes, while the smaller peyevmal, with its slightly bulging sides and drawn-in mouth, was a delicate counterpart.

Crafting a single basket was a labor of endurance—ten to eighteen wraps per inch, thousands of stitches for even a modest piece. Yet the Luiseño also wove rougher, open-work baskets from Juncus rushes for sifting, leaching acorn meal, or gathering cactus. Unlike some Southern California tribes, who sealed rush baskets with asphaltum for waterproofing, the Luiseño did not, relying instead on the tight construction of their coiled wares.

Luiseño Material Culture: Bows and Arrows

The Luiseño’s weapons were as finely crafted as their baskets, designed for the hunt across Southern California’s varied terrain. Their bows, typically five feet long, tapered gracefully from a thicker center to springy ends, maximizing force. Willow was the common choice, but elder, ash, or the rare mountain ash from Palomar’s slopes were prized for superior resilience. The arrows, equally sophisticated, paired a cane mainshaft (Elymus condensatus) with a fire-hardened greasewood foreshaft (Adenostoma fasciculatum), glued with asphaltum and bound with sinew.

Three hawk feathers, twisted slightly to impart a rifling spin, ensured a straight flight. Stone points, chipped with deer-antler tools into concave-based teket, were secured with sinew and greasewood gum. However, smaller arrows of arrow-weed (Pluchea borealis) or tall weeds like Artemisia heterophylla lacked such tips. Straightening arrows was an art in itself, using a heated, grooved yaulash stone to shape the shaft.

Bowstrings, woven from dogbane, milkweed, or sinew, were typically two- or three-ply, with sinew strings always triple-stranded for strength. Quivers of fox or wildcat skin, lined with tree moss to cushion arrowheads, hung over the shoulder. The Luiseño’s archery was precise—an average bow carried an arrow a hundred yards, though its effective range was closer to fifty. Unstrung when idle to preserve tension, these bows were tools of survival, their craftsmanship reflecting the Luiseño’s intimate knowledge of wood, fiber, and stone.

The Luiseño’s material culture was no mere collection of objects but a dialogue with their environment. In a region where coastal Chumash paddled tomol canoes and interior Cahuilla hunted bighorn sheep, the Luiseño carved out a distinctive niche. Their villages, ranging from modest desert hamlets to larger settlements, housed conical homes of arrowweed or tule, while clay vessels and baskets bore the mark of local resources and ingenuity. Unlike the soapstone carvings of Catalina Island or the asphaltum-sealed baskets of other tribes, the Luiseño’s artifacts leaned on the immediate—grass, sumac, willow, and stone—transformed through skill into tools of sustenance and survival.

Sources

Castillo, Edward D. “Short Overview of California Indian History.” State of California Native American Heritage Commission. State of California, 2020. http://nahc.ca.gov/resources/california-indian-history/.

Putnam, Frederic Ward, ed. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology. Vol. 8. Berkeley: The University Press, 1906–1907.

Sparkman, Philip Stedman. The Culture of the Luiseño Indians. Berkeley, California: The University Press, 1908.