Theodore Roosevelt is often seen as the face of American imperialism. Still, it would be unjust to attribute the entirety of the nation’s imperial ambitions—defined as the pursuit of territorial control, economic dominance, and geopolitical influence through military and diplomatic means—solely to him. He was, after all, an inheritor of a system, not its creator. Like many Americans before him, Roosevelt was an enthusiastic promoter of expansion, but the forces driving America outward had gathered long before his birth in 1858.

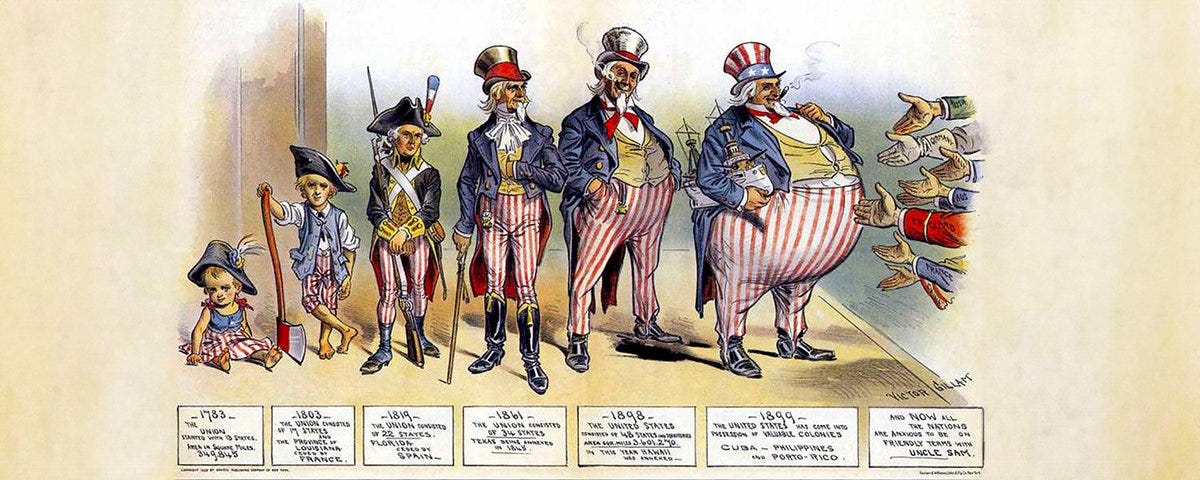

The roots of this momentum trace back to the 1840s, when the Mexican-American War added vast territories to the U.S., and the ideology of Manifest Destiny, which framed expansion as a divine right. By the time Roosevelt strode onto the world stage, the machinery of empire was already well in motion, fueled by economic interests, naval strategy, and a belief in American exceptionalism.

The history of American intervention abroad stretches back to the mid-nineteenth century, often as reactive measures that evolved into a pattern of dominance. In November 1852, U.S. Marines landed in Buenos Aires during Argentina’s civil strife, a brief action to protect American citizens and trade interests amid a diplomatic dispute, not yet a grand imperial strategy. The following year, in July 1854, U.S. forces bombarded and razed San Juan del Norte (Greytown), Nicaragua, after a local mob injured an American diplomat—an escalation framed as defending lives and property but signaling growing assertiveness in Central America, where U.S. fruit and shipping companies would later thrive.

Commodore Matthew Perry followed similarly in the Pacific when he arrived in Japan in 1853 with a squadron of black-hulled warships, forcing the once-isolated nation to open its ports to American trade under the 1854 Treaty of Kanagawa. While awaiting Japan’s reply, Perry landed Marines in the Ryukyu and Bonin Islands, negotiating coaling stations and securing strategic footholds—moves mirroring British and French efforts to counter European rivals in Asia.

This pattern of intervention repeated itself in 1859, when U.S. forces protected American lives and commerce in Shanghai during the Taiping Rebellion. A year later, in 1860, troops landed in Africa at Kissembo, a minor trading post in Portuguese-controlled Angola, to safeguard foreign property during local unrest—a small but telling example of America’s expanding reach.

By 1893, Hawaii became a pivotal test. Officially, U.S. Marines landed to maintain order amid tensions between American sugar planters and Queen Liliʻuokalani’s government. They facilitated her overthrow by a coalition of U.S. settlers and businessmen. President Cleveland condemned the act and sought to restore the queen, but his efforts failed; annexation followed in 1898 under McKinley, cementing Hawaii as a U.S. territory—an outcome Native Hawaiians bitterly resented as a loss of sovereignty.

In 1894, intervention struck again in Nicaragua, where U.S. forces landed in Bluefields to protect American economic stakes—namely, trading posts and plantations—following a local revolution. By then, the U.S. had intervened abroad over a dozen times since 1850, a frequency dwarfed by Britain’s colonial ventures but notable for a young nation. The wheels of empire, it seemed, were turning ever faster.

The United States Before the War

Though the United States had engaged in international economic, military, and cultural activities since the eighteenth century, the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars (1898–1902) would mark a pivotal, more aggressive shift in its global interventions. By waging war against Spain and suppressing revolution in the Philippines, the nation could broaden and bolster its worldwide presence.

Over the next two decades, this expansion drew the U.S. deeper into international politics, especially Latin America. These conflicts and territorial consequences forced Americans to grapple with imperialism’s ideological dilemmas: Should the U.S. embrace empire? Did foreign interventions and territorial seizures clash with its democratic roots? How would it govern its territories, and could colonial subjects be integrated as citizens?

The Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars thrust these long-simmering questions about American expansion into the forefront. There was already a feeling of a new sort of Manifest Destiny, and after conquering the West, venturing to new horizons seemed inevitable. On the eve of the Spanish-American War, a Washington Post editorial on April 10, 1898, captured the national mood:

“A new consciousness seems to have come upon us—the consciousness of strength—and with it a new appetite, the yearning to show our strength… We are face to face with a strange destiny. The taste of Empire is in the mouth of the people.”

Not everyone savored this flavor. The Cleveland Gazette, a Black-owned newspaper, critiqued the hypocrisy of a nation decrying Spanish oppression in Cuba while ignoring racial terror at home. In its May 7, 1898 issue, it asked:

“Is America any better than Spain? Has she not subjects in her very midst who are murdered daily without a trial of judge or jury? Has she not subjects in her own borders whose children are half-fed and half-clothed, because their father’s skin is black… Yet the Negro is loyal to his country’s flag.”

This perspective underscored a bitter irony: Black Americans, denied justice amid rising lynchings (over 1,000 documented between 1890 and 1900), saw little “civilization” in this march of empire.

The expansion seemed inevitable for those in power—military officers, politicians, business leaders, and farmers eyeing export markets. Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, a U.S. naval strategist, emerged as a key voice, arguing in his 1890 book The Influence of Sea Power Upon History that great nations thrived on maritime supremacy. His ideas, which inspired the naval buildup for the Spanish-American War, profoundly shaped Roosevelt and Senator Henry Cabot Lodge. In a March 1895 Forum article, Lodge declared:

“In the interests of our commerce… we should build the Nicaragua canal and for the protection of that canal and for the sake of our commercial supremacy in the Pacific we should control the Hawaiian Islands and maintain our influence in Samoa… The great nations are rapidly absorbing for their future expansion and their present defense all the waste places of the earth. It is a movement which makes for civilization and the advancement of the race. As one of the greatest nations of the world, the United States must not fall out of the line of march.”

Lodge’s vision echoed Britain’s scramble for Africa, though America’s empire leaned more on economic penetration than formal colonies.

By 1890, a network of like-minded men—Roosevelt, Lodge, and Mahan—began exchanging ideas, reinforcing each other’s belief in American expansionism. As Assistant Secretary of the Navy in 1897, Roosevelt worked to free Mahan from sea duty, enabling him to evangelize naval power full-time.

Hawaii became an early proving ground. In 1893, still a private citizen, Roosevelt fumed over the U.S. hesitancy to annex the islands, calling it “a crime against white civilization” in a letter to Mahan. His zeal for action shone in a June 1897 speech at the Naval War College:

“All the great masterful races have been fighting races… No triumph of peace is quite so great as the supreme triumph of war.”

Roosevelt’s views weren’t limited to expansion. After a mob lynched eleven Italian immigrants in New Orleans in 1891, he publicly urged compensation to Italy to avoid a diplomatic rift. Privately, in a March 21, 1891, letter to his sister Anna, he wrote that he thought the lynching was “rather a good thing,” boasting he’d told “various dago diplomats” as much over dinner—a remark reflecting his casual racism toward non-Anglo groups, including Italians and later Japanese immigrants.

Wealth and Gaze Toward War

While expansionist politicians shaped policy, economic forces propelled them. By 1898, American capital abroad exceeded $1 billion—much of it in Latin America and the Caribbean—with exports rivaling all nations except Britain, reaching $1.3 billion annually.

Industry titans like John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil dominated, controlling 90% of U.S. kerosene exports and 70% of the global supply by 1891, thanks to Asian and European markets. In Hawaii, sugar planters like Sanford Dole lobbied for annexation to secure tariff-free access to U.S. consumers, a goal realized in 1898.

By winter 1898, American business and politics turned southward, their gaze fixed on the smoldering conflict in Cuba. The island had long been restless under Spanish rule, and its people rose in rebellion continuously through the nineteenth century. There were many attempts, from both Cubans and Americans, to annex Cuba to the United States.

In the winter of 1823, John Quincy Adams, then Secretary of State, gazed beyond the horizon to Cuba, that emerald isle shimmering in the Caribbean sun, and penned a vision he called the “ripe fruit” theory. To him, Cuba was a prize destined to tumble into America’s grasp, just as Florida had slipped from Spain’s fingers only a few years before. He argued that it was not a question of if, but when.

By 1848, that whisper had grown into a bold shout. President James K. Polk, a man of stern resolve and westward dreams, stood ready to claim Cuba not with patience but with coin. He sent word to Madrid, Spain: $100 million for the island—a fortune in those days, enough to turn heads. Spain, proud and unyielding, sent back a curt refusal. Polk’s offer lay dead on the table, but the idea of Cuba as America’s own refused to fade.

Six years later, in 1854, that ghost took flesh in an audacious scheme known as the Ostend Manifesto. Three American diplomats—Pierre Soulé, James Buchanan, and John Mason—gathered in a smoky Belgian parlor and hatched a plan as brash as it was reckless. Cuba, they declared, must be America’s, even if it meant seizing it by force. They saw it as a southern stronghold, a place to stretch the roots of slavery. But when their words leaked to the public, a storm broke loose. Northern voices cried foul, abolitionists thundered against the plot, and the nation recoiled. The manifesto crumpled under the weight of its ambition.

Then came the Ten Years’ War, a ragged, desperate struggle that erupted in 1868 as Cubans rose against their Spanish masters. For a decade, the island trembled with cannon fire and the shouts of rebels who dreamed of freedom. Some among them cast hopeful eyes northward, pleading for American aid—or even annexation. In the United States, a chorus of sympathizers, adventurers, and profiteers echoed the call, urging intervention. Yet Washington held back—its hands stayed by war-weary caution and the memory of Ostend’s failure. The rebellion faltered, Spain tightened its grip, and Cuba remained beyond America’s reach.

But history, like the sea, has its tides, and by 1898, the current had turned. The Spanish-American War burst forth, a tempest of steel and flame that swept the U.S. to victory in months. When the smoke cleared, Cuba lay in American hands, wrested from Spain alongside Puerto Rico and the Philippines. To men in Washington—politicians with maps unrolled and generals with medals gleaming—the island seemed a glittering prize, ripe at last.

America Goes to War

By 1898, after a Cuban uprising had begun in 1895, the Spanish general, Valeriano Weyler, had spent two years trying to suffocate it. His method was ruthless. Entire Cuban communities were uprooted and forced into military-controlled camps in a brutal policy of reconcentración. Thousands died of disease and starvation.

The suffering, exaggerated and splashed across the pages of America’s largest newspapers, ignited a fury among the American public. In the United States, cries of Cuba Libre! rang out, fueled by Cuban expatriates and their allies. While President William McKinley insisted on a diplomatic approach, his patience was thinning. He warned that American lives and investments were at risk, and something had to be done.

In January 1898, McKinley took action. The battleship Maine was dispatched to Havana Harbor, a silent but unmistakable message to Spain. For two weeks, the vessel sat undisturbed. Then, on the night of February 15, an explosion ripped through the ship. The Maine sank within moments, three-quarters of her crew lost to the depths. An official naval inquiry was launched, but before any conclusions could be reached, American newspapers had already decided the cause: Spanish treachery.

William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal led the charge. The so-called "yellow press" or "yellow journalism" demanded vengeance, running lurid headlines that stoked the anger of the American people. When diplomatic efforts collapsed, McKinley and Congress made it official: on April 25, the United States declared war on Spain.

The war, once started, was over almost before it had begun. Spain’s decaying colonial forces crumbled before the surging might of the United States. On May 1, in the Pacific, Commodore George Dewey met the Spanish fleet at Manila Bay and annihilated it. Across the world, in Cuba, American troops landed in June, pressing forward to capture the heights of Santiago.

In what would become the war’s most famous battle, Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Riders—a volunteer cavalry regiment Roosevelt had personally assembled—charged San Juan Hill, securing victory and launching Roosevelt into national stardom. Critics like philosopher William James recoiled at such bravado. In a 1901 essay, James wrote of Roosevelt,

“He gushes over war as the ideal condition of human society, for the manly strenuousness which it involves, and treats peace as a condition of blubberlike and swollen ignobility, fit only for huckstering weaklings, dwellings in gray twilight and heedless of the higher life…”

On July 17, Santiago fell. By August 12, Spain had agreed to a ceasefire. By December, the two nations had settled the conflict through the Treaty of Paris. The war had lasted only fifteen weeks.

The terms of the treaty were monumental. The United States acquired Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines—territories that, for the first time, placed America firmly in the role of an overseas imperial power. Secretary of State John Hay called it a “splndid little war.” For many Americans, it seemed providential, a righteous triumph. The Reverend Lyman Abbott declared that the American people were “an elect people of God,” while Senator Albert J. Beveridge went further. The United States, he argued, had a duty—a mission—to expand across the globe.

“The great nations are rapidly absorbing for their future expansion all the waste places of the earth,” he proclaimed. “As one of the greatest nations of the world, the United States must not fall out of the line of march.”

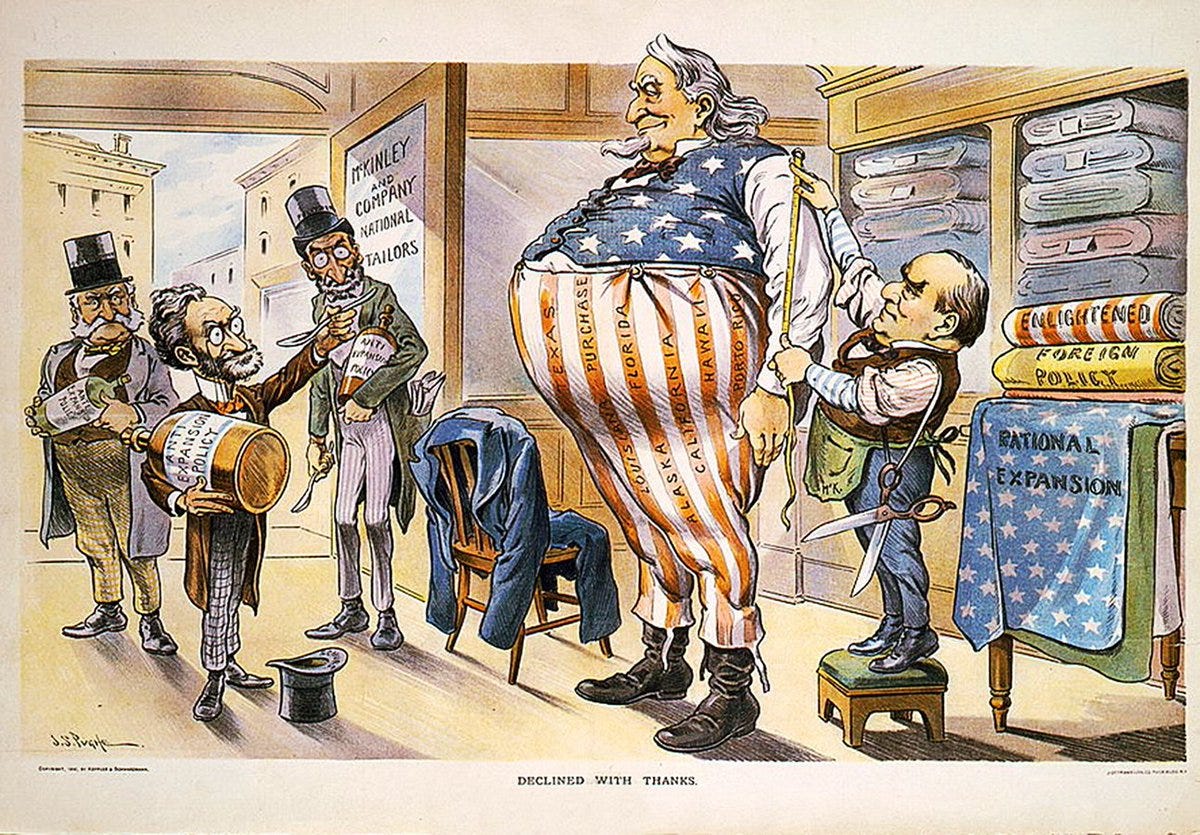

However, America’s sudden expansion was no simple victory. Even as patriotic celebrations filled the streets, a growing unease took root. In July 1898, at the urging of American business interests, the United States annexed Hawaii, long a target of U.S. sugar planters and investors who had orchestrated the overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani. The Spanish territories, too, raised difficult questions. Many Americans welcomed the new possessions as vital stepping stones for trade and influence. Others recoiled at the notion of empire, warning that colonial rule contradicted the very ideals on which the nation had been founded.

Nowhere was the debate more heated than in the Philippines. The islands had been an afterthought in the war’s opening days, but as the smoke cleared, it became evident that they were far more than a battlefield—they were a prize. Filipino leader Emilio Aguinaldo had expected that American forces would support Philippine independence. Instead, U.S. troops seized Manila, refusing to let Filipino forces enter the capital. It was an ominous sign of things to come. The answer came in 1899. That year, Congress ratified the Treaty of Paris, officially purchasing the Philippines from Spain for $20 million.

For some, the answer was clear. Protestant missionaries framed the expansion as a moral duty, a Christian mission to uplift the world’s "heathen" peoples. President McKinley insisted that America’s duty was to bring civilization and Christianity to the islands. Business leaders saw new markets, resources, and opportunities for profit. But for others, the contradiction was too stark. The Anti-Imperialist League protested that the United States—once a colony that had fought for its liberty—was now subjugating others. What followed, however, was not a civilizing mission but a war.

From 1899 to 1902, the United States fought to crush the Philippine independence movement. The war—called the Philippine Insurrection by Americans, but the Philippine-American War by those who lived through it—was long, bloody, and far deadlier than the war against Spain. The jungles and villages of the Philippines became a battleground where the rules of engagement blurred. Reports of atrocities from both sides filled the press. Some Americans likened it to the Indian Wars of the previous century—a campaign to subdue a "savage" people. American forces found themselves waging a brutal counterinsurgency, their tactics eerily reminiscent of Spain’s reconcentración policies in Cuba.

Even those who supported expansion worried about its consequences. A 1900 political cartoon depicted an overweight Uncle Sam being fitted for a new, larger suit—symbolizing an America growing perhaps too fast for its own good. And yet, Americans have debated whether they welcomed or lamented being a global power.

Americans could no longer ignore the reality of their new status. Still, the fighting continued. McKinley sent the Taft Commission to establish a civilian government in the islands, and in 1901, U.S. forces captured Emilio Aguinaldo. Though President Theodore Roosevelt officially declared the war over in 1902, Filipino resistance lingered for years.

The Roosevelt Era Begins

No man embodied this imperial moment more than Theodore Roosevelt. Already a war hero, he had risen rapidly—Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Governor of New York, Vice President, and President after McKinley’s assassination. Under his leadership, America’s reach would stretch further still. Roosevelt believed in a strong navy, a strong presence in Latin America, and a forceful role on the world stage.

His policies would reshape the hemisphere. His Big Stick diplomacy would define American foreign affairs for years to come. His ambitions would help build the Panama Canal, extend U.S. influence over Cuba and Puerto Rico, and put the United States at the center of global affairs.

This fusion of business and politics crystallized under Roosevelt’s presidency (1901-1909). Often hailed as a “trust-buster,” his approach was pragmatic, not ideological. Using the Sherman Antitrust Act, he targeted 43 “bad trusts” that stifled competition, like the Northern Securities Company, a railroad giant dissolved by a 1904 Supreme Court ruling that rattled Wall Street. He subjectively left “Good trusts,” like U.S. Steel, intact, believing they served national interests, but also in the interest of his political persona.

Labor disputes tested his leadership, too. In 1902, a coal strike by 140,000 workers threatened to freeze the economy. When mine owners refused to negotiate, Roosevelt threatened to seize the mines with federal troops—an unprecedented move. Arbitration followed: workers won a 10% wage hike and shorter hours, though owners refused union recognition. Roosevelt cast this as part of his “Square Deal,” a pledge to balance the needs of workers, consumers, and businesses—a philosophy at odds with his imperial aggression yet central to his domestic legacy.

Roosevelt’s contradictions extended to conservation, where he became the first president to prioritize it nationally. By 1909, he had protected over 230 million acres—five times Yellowstone’s size—creating five national parks (e.g., Yosemite expansions), 150 national forests, and 18 national monuments under the 1906 Antiquities Act. Eager to log or mine these lands, business interests bristled, but Roosevelt saw conservation as safeguarding America’s future strength.

Roosevelt’s foreign policy, encapsulated as “speak softly and carry a big stick,” reflected his vision of America as a global power. The Panama Canal epitomized this. When Colombia balked at selling the canal zone in 1903, the U.S. backed a Panamanian revolt, securing the territory within weeks—a move costing thousands of worker lives during construction and stoking Latin American distrust. In 1904, the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine warned Europe to stay out of Latin America while asserting U.S. authority to intervene there, turning the region into America’s sphere of influence—a role Britain played in Africa.

Across the Pacific, Roosevelt brokered peace between Russia and Japan in 1905, earning the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize. Yet tensions with Japan lingered, fueled by anti-Japanese sentiment in California. His 1907 “Gentlemen’s Agreement” persuaded Japan to curb emigration voluntarily, though loopholes (e.g., family reunification) let some slip through, easing but not ending friction.

By Roosevelt’s exit in 1909, America was a world power. His successor, William Howard Taft, pursued “dollar diplomacy,” using economic leverage to extend U.S. influence, a quieter echo of Roosevelt’s bluster. The era of the American empire had begun, shaped by men who saw strength, commerce, and destiny as intertwined. Between 1898 and 1914, U.S. trade grew by 50%, and interventions in Latin America alone numbered over 20—markers of a rising hegemon.

It was, as Lodge had said, a march of civilization. Whether it was progress—a beacon of modernity—or power in new clothes, cloaking exploitation in noble rhetoric was a question for the next century. The resentment of colonized peoples, from Hawaii to Panama, and the uneven spoils at home, where Black and working-class Americans saw little gain, suggest it was both—and neither entirely.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

OpenStax. "U.S. History." OpenStax, 2016.

Locke, Joseph L., and Ben Wright, eds. The American Yawp: A Free and Online, Collaboratively Built American History Textbook. Stanford University Press, 2019. https://www.americanyawp.com.

Schweikart, Larry, and Michael Allen. A Patriot's History of the United States: From Columbus's Great Discovery to the War on Terror. New York: Sentinel, 2004.

Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. New York: Harper & Row, 1980.