In the long American story—a story of ideals tested, of citizens rising not by birthright but by effort—there was a recurring chapter: the call to serve. Not to rule, not to command, but to serve. On April 15, 2025—Tax Day—I walked through the doors of the Riverside County Registrar of Voters office with that call ringing quietly but firmly in my heart.

I carried no grand entourage. No television crews. Just a pen, a folder, and the kind of determination that history always favored: the steady, unglamorous kind. I wasn’t there as a politician. I was there as a teacher, a coach, a neighbor, and a believer in the power of public education—especially the overlooked, underfunded engine of opportunity that was the community college.

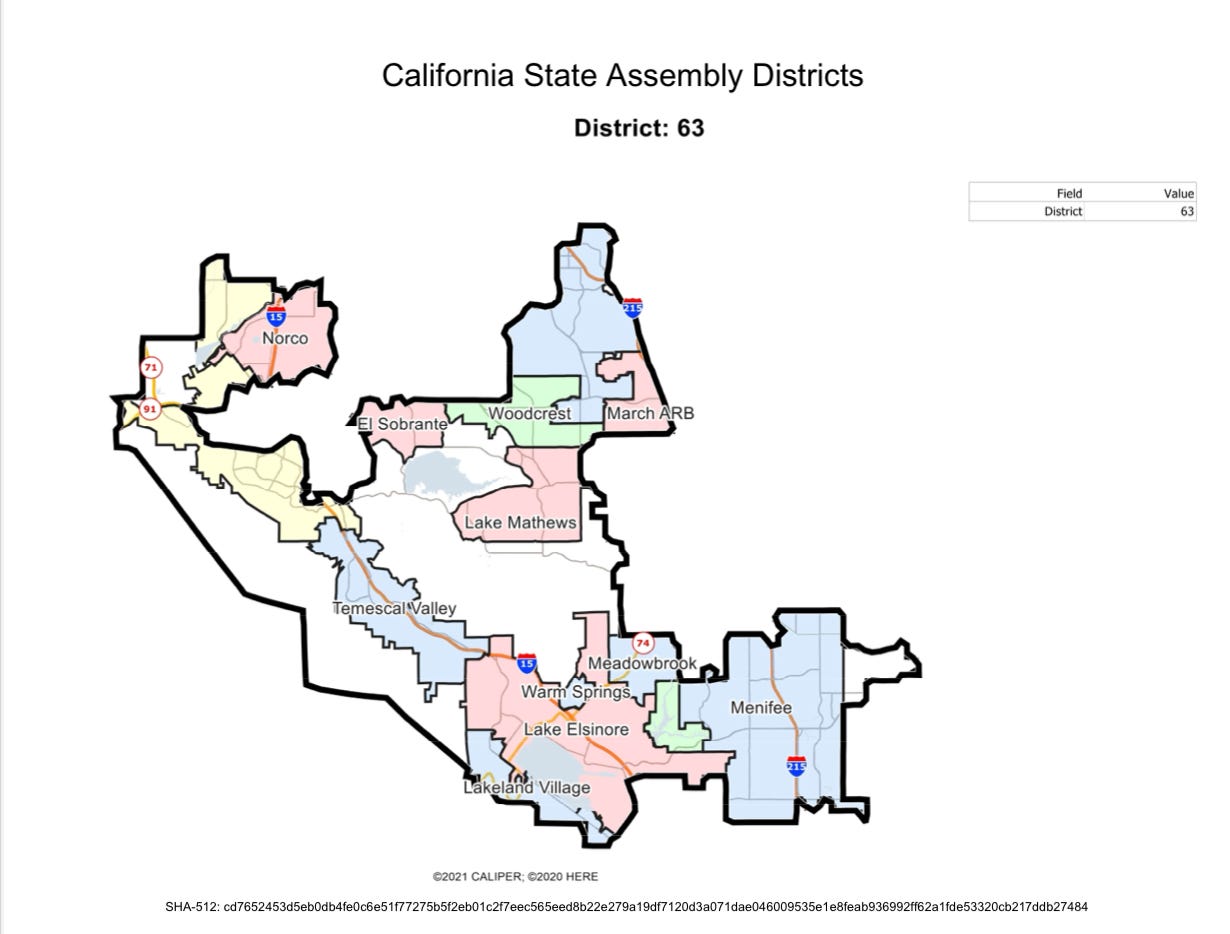

The task was plain: file the paperwork to run for California’s 63rd Assembly District, a district that wound its way through Corona, Norco, Menifee, and the stories of the people who lived there. The clerks handed me ten sheets of paper—each with room for ten signatures. One hundred forty-three names. That was what it took to get on the ballot without paying the $1,300 filing fee. Not money. People.

It felt democratic in the best sense—every name worth $9.27, every conversation a small referendum on trust and shared hope. I asked for extra sheets—they gave them willingly. I asked for a map—they didn’t have one.

Boundaries, they said, would take two weeks to retrieve from GIS. And here was the curious thing: the lines of the 63rd District danced along streets and neighborhoods like a ribbon in the wind. Ontario Boulevard, for example, cut through Corona like a seam—with churches and mosques on the south side falling inside the district, and their neighbors across the street falling out.

It felt hard not to think of gerrymandering, and harder still not to recall Governor Schwarzenegger’s old warnings about it. Perhaps he was onto something.

With a special election fast approaching—June 25—I had nine weeks to launch a campaign from scratch. No party infrastructure. No big donors on speed dial. Just a public-school work ethic and the belief that people still wanted someone to listen before they led.

My opponents had already received the public blessings of the local political class—endorsements announced, alliances sealed. I understood it. But I also sensed the question hanging in the air: was there room for someone different?

Someone who had taught California’s history, not just read it. Someone who had stood in front of classrooms, not campaign rallies. Someone who had seen how a well-timed scholarship or a community college counselor could tilt the arc of a young life.

I turned to wedrawthelines.ca.gov for a better map—finally, a clear view of the district I hoped to represent. It became my Rosetta Stone, a tool not just for strategy but for understanding. I pored over it late at night, tracing freeways and neighborhoods, imagining the lives within them. This wasn’t just about running for office—it was about building something that could outlast a campaign.

On the morning of April 16, I began reaching out to friends and neighbors. From the foothills of Corona to the outer roads of Menifee, I asked for help—not in dollars, but in doors. Not in slogans, but in stories. I asked people to sign not just their names, but their confidence. Because that was what every campaign really was: a test of faith between the people and those who would speak on their behalf.

I saw myself as a bridge—not just between policies, but between experiences. Like the Democrat in the race, I had spent years in classrooms. Like the Republican, I had built and run a business and understood the toll of crime and regulation. But unlike either of them, I had spent time in Sacramento, fighting for grants, where I learned not only how to get support, but how trust was too often squandered.

Then, as if to remind me that history was made in moments, not headlines, I met the president of the Lake Elsinore Valley Water District. We spoke not of politics, but of water, schools, and the delicate threads that bound a community. It was brief, but galvanizing.

And so I began—not with certainty of outcome, but with conviction of purpose. With sheets of paper under my arm and the memory of students who changed their lives through education, I set out. Door by door. Block by block. Believing, as generations before had believed, that in the great experiment of democracy, the smallest voices often carried the most truth.

Until next time…goodbye now.