From the sun-drenched hills of Sicily to the bustling streets of New York, the Cristadoro family wove a rich tapestry of art, ambition, and resilience, their story a vibrant thread in the fabric of American cultural history. Sicily, a land where emperors once held sway and gladiators clashed with beasts, cradled artists of immortal renown—Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo—whose genius cast long shadows. Into this lineage was born Charles Clarence Herbert Cristadoro, a second-generation American whose Sicilian roots pulsed with the passion of his forebears.

The Cristadoro saga in America began with Joseph Cristadoro, born in Palermo on February 2, 1817, a man who carried Sicily’s fire to the New World. A proud New Yorker, diminutive at five feet six, with gray eyes, a prominent nose, and dark brown hair framing a full Italian face, Joseph embodied the American dream. He amassed wealth through Cristadoro’s Hair Dye, a product lauded for its natural shades of black and brown, its name emblazoned on glass bottles that reached households from across the country.

Joseph Cristadoro’s home in New York became a cultural beacon, hosting gatherings of artists and intellectuals, its walls adorned with an exquisite collection of old masters, many Italian. Joseph’s legacy, both fiscal and cultural, endured in the prestigious Green-Wood Cemetery, where he and his wife, Maria, were laid to rest alongside many of their children.

Joseph’s artistic fervor flowed into his sons, Alexander and Charles Clarence Cristadoro I. Alexander followed his father’s path, managing the hair dye empire and gracing newspaper advertisements. At the same time, Charles charted a different course. Born in 1855, he sought mercantile success, sailing to London in 1878 aboard the S.S. City of Brussels. There, he peddled liver pads for the Holman Liver Pad Company, touting their dubious benefits to the vital forces of nerves and blood.

The venture faltered, but London brought him a greater prize: on October 1, 1878, he wed Julia Gertrude Fairchild at St. Marylebone Parish, a union announced in the New York Times. Julia, a Cincinnati native, became his steadfast partner, her devotion unwavering through the trials to come. The couple’s first child, Agnes Gertrude, arrived in 1880 in London, followed by Bertha Carina in 1881.

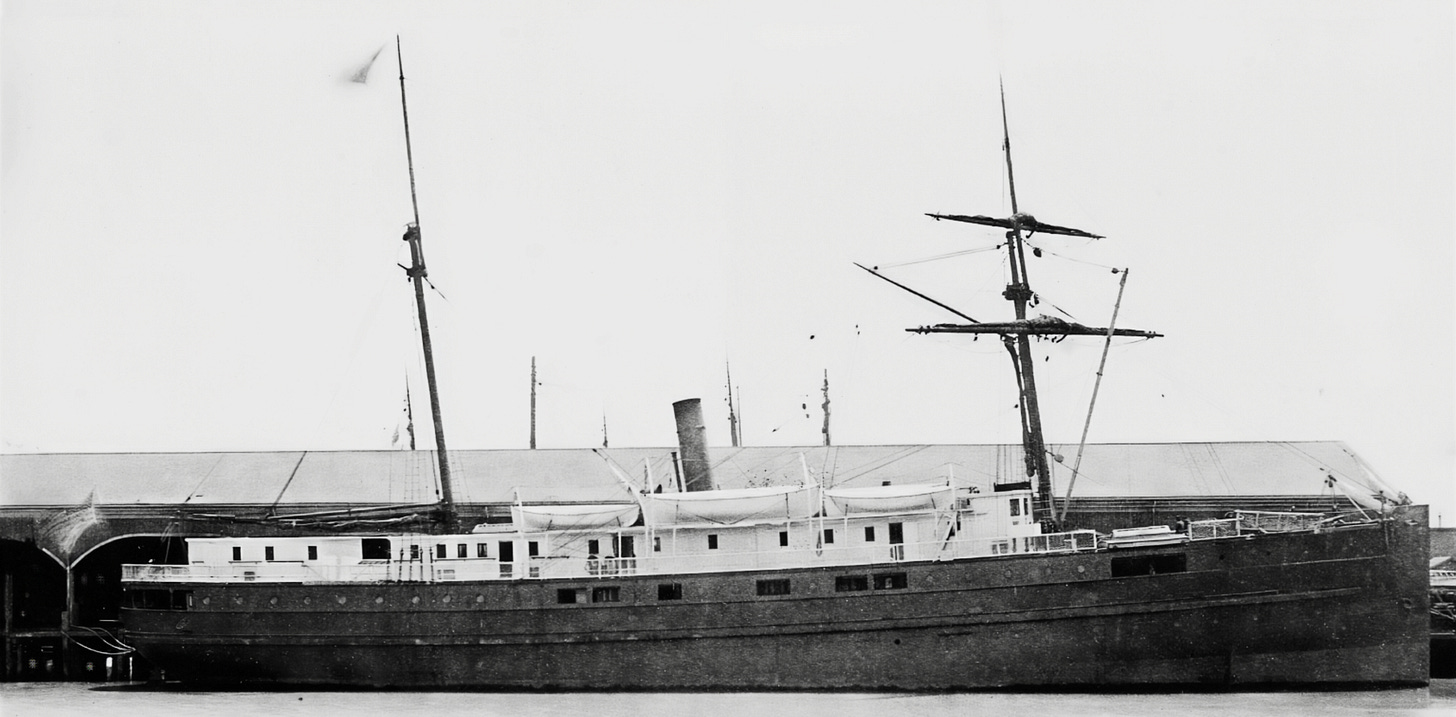

The family lived comfortably, attended by a nurse, Emma Redding, and a chef, Margaret Shea, in a well-appointed London home. In July 1881, with Julia four months pregnant, they returned to New York aboard the S.S. City of Chester. On November 18, 1881, Charles Clarence Herbert Cristadoro—Cris—was born. A third daughter, Mabel Evelyn, joined the family in 1893, later marrying Harrison Hodges, a railroad magnate and family friend nearly four decades her senior, whose courtship with toys and trinkets drew her into a life apart from the Cristadoros.

In New York, the family thrived until Joseph’s death in 1889, prompting a move to St. Paul, Minnesota. There, Charles reinvented himself as an inventor, specializing in box-making machinery and publishing a treatise on calculating square footage for boxes. His ingenuity shone, but tragedy struck in 1906. Rushing to retrieve a revolver from his desk in the German-American Bank Building for his son’s impending trip to California, Charles caught the hammer, discharging a bullet into his abdomen.

Found unconscious, he was rushed to St. Luke’s Hospital, where surgeons extracted the bullet. Though he survived, paralysis confined him to a wheelchair, a cruel pivot in a life of ceaseless ambition. The injury spurred the family’s relocation to San Diego in 1906, where the milder climate eased Charles’ suffering. In a Point Loma bungalow overlooking the bay, he became the “Sage of the Lath House,” a figure of intellectual vigor despite his physical constraints.

Seated in his chair, pipe in hand, he wrote prolifically—articles, letters, and books—often for no pay, driven by a passion for public service. His writings, published in outlets like the San Francisco Call, ranged from nostalgic reflections on baseball to agricultural treatises that earned him acclaim along the California coast. Even the president of the University of California, Berkeley, sought his counsel, marveling at a mind with “the mental energy of a dozen men.” Charles’s resilience was profound. “You may break, you may shatter, the vase if you will, but the scent of the roses will cling to it still,” he wrote, defying his disability. His pen became his solace, capturing a sportsman’s longing for the hunt and the forest’s embrace, pursuits now denied him.

In 1916, he clashed with St. Paul’s mayor over a $1,000 claim for paintings lost in a library fire, rejecting a paltry $250 settlement with characteristic tenacity. His daughter Agnes, an artist in her own right, inherited his creative spirit, later marrying architect Edwin T. Banning and preserving Cris’s finest works. Bertha, meanwhile, pursued agriculture at the University of Minnesota, her later years obscured by marriage, while Mabel’s life with Hodges faded from the family’s narrative.

Cris, shaped by this legacy of art and perseverance, rarely spoke of his family in later years, guarding his past as if reserving it for history’s discovery. Yet his father’s influence was indelible, a foundation for the achievements that would elevate him among America’s artistic luminaries, from New York’s cultural salons, from London’s promise to California’s shores. Cristadoro carved a path of creativity and courage, their story a testament to the enduring power of heritage and heart.

SOURCES | BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ancestry.com. 1881 England Census. Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations, 2004.

Ancestry.com. 1920 United States Federal Census. Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations, 2010. http://search.ancestrylibrary.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?h=3056014&db=1920usfedcen&indiv=try.

Ancestry.com. London Marriages and Banns, 1754–1921. Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations, 2010. http://search.ancestrylibrary.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?h=4092294&db=LMAmarriages&indiv=try.

Ancestry.com. Minnesota Territorial and State Censuses, 1840–1905. Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations, 2007.

Ancestry.com. U.S. Passport Applications, 1795–1925. Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations, 2007.

Anglo-American Times. “Arrival of Passengers.” Anglo-American Times, February 1, 1878.

Coulter, Mary J. “Miniature Sculpture by San Diego Artist Shows Consummate Skill.” San Diego Union, May 1926.

Cristadoro, Charles. “An Inheritance of Rods and Guns.” The Overland Monthly 58 (July–December 1911): 133.

Cristadoro, Charles. “Baseball 50 Years Ago.” San Francisco Call, March 19, 1911.

Cristadoro, Charles. “Interesting Occupation for the Convalescent.” Dietetic and Hygienic Gazette 30, no. 1 (January 1914): 492–93.

Defebaugh, Edgar Harvey. Obituary: Charles Cristadoro. Chicago: Lumber Buyers’ Publishing Corporation, 1896–1951.

Gefen, Gerard, Jean-Bernard Naudin, and Fanny Caletafi di Canalotti. Sicily: Land of the Leopard Princes. London: I. B. Tauris, 2001.

Green-Wood Cemetery. Green-Wood: A National Historic Landmark. http://www.green-wood.com/burial_results/index.php.

Kamerling, Bruce. “Early Sculpture and Sculptors in San Diego.” Edited by Thomas L. Scharf. The Journal of San Diego History 35, no. 3 (1989). http://www.sandiegohistory.org/journal/89summer/sculptors.html.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Notes.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 5, no. 3 (March 1910): 81.

New York Times. “Died.” New York Times, June 29, 1889.

New York Times. “Married: Cristadoro–Fairchild.” New York Times, November 21, 1878.

New York Times. “Passengers Arrived.” New York Times, July 11, 1881.

Oakland Tribune. “Weds Daughter of Friend at 62 Years.” Oakland Tribune, July 2, 1916.

Saint Paul Public Library. “Spurns $250 Offer for Lost Pictures.” SPPL Photo Morgue, May 26, 1916.

San Francisco Sunday Call. “Finding the Statue: How a Young Artist Gave San Diego Its Gigantic Neptune.” San Francisco Sunday Call 110, no. 67, August 6, 1911.

Steele, Rufus. “A Giant Sitting Down.” Sunset, the Pacific Monthly 33, no. 1 (July 1914): 1186.

The Packages. “Mr. Cristadoro Severely Injured.” The Packages 9 (January 1906): 31.

St. Louis Republic. “Mayor Wells Welcomes National Boxmakers.” St. Louis Republic, February 19, 1904.

The University of Minnesota. The Annual Register. St. Paul: The University of Minnesota, 1905.

U.S. Library of Congress. Catalogue of Title Entries of Books and Other Articles. Vol. 20. Washington, DC: 1899.

Week’s News. “Holman Liver Company.” Week’s News, January 18, 1879.