The late 19th and early 20th centuries marked a transformative period in the history of the United States. The nation emerged as a global economic powerhouse fueled by technological innovation, industrial expansion, and profound social change. This era reshaped the American landscape.

Railroads crisscrossed the continent, linking once-distant regions into a cohesive economic network. Inventors revolutionized communication and energy, while industries thrived on new materials and production methods.

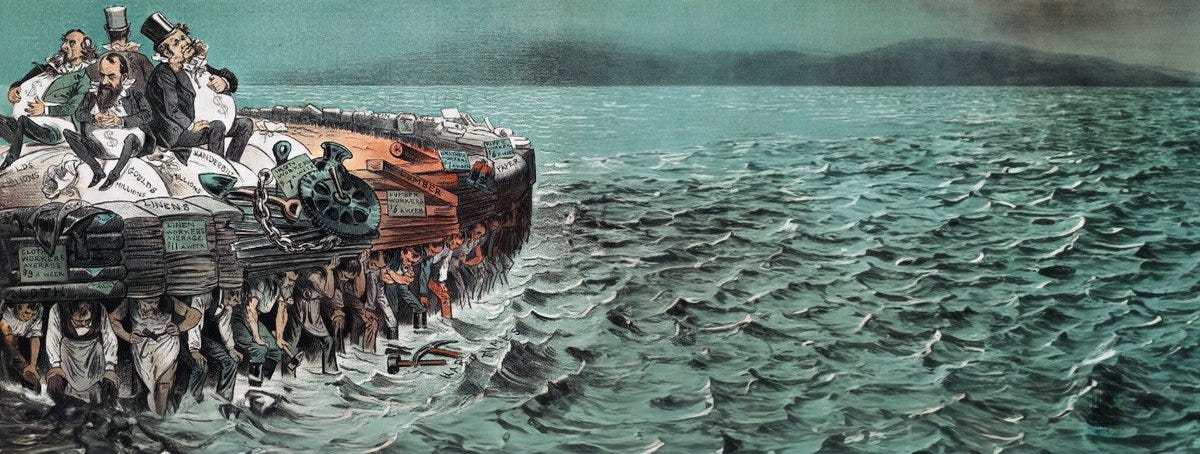

However, this progress was not without cost. The exploitation of labor, displacement of Native populations, and glaring social inequalities highlighted the tensions underlying this rapid growth. This narrative explores the forces and figures that defined America’s rise as a new economic power.

Expanding on a Nationwide Scale

Profound territorial and industrial expansion fueled the United States’ emergence as an economic powerhouse in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Central to this growth was the military conquest of America’s inland empire and the dispossession of Native Americans from their ancestral lands. These actions enabled the development of an elaborate and expansive railroad system that stitched the vast nation together, enabling the efficient movement of goods, people, and ideas.

By 1900, the United States boasted over 193,000 miles of railroad track, surpassing the combined rail networks of Europe and Russia. These railroads, privately owned but heavily subsidized by publicly financed land grants, epitomized the spirit of the Gilded Age—a period of astonishing wealth accumulation and systemic inequality. This network of steel rails transformed the nation’s economic landscape, fostering the rapid industrialization that defined the era.

Transformative Inventions

Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Edison exemplified the technological ingenuity of the period. Bell, a Scottish immigrant, revolutionized communication with the invention of the telephone, allowing Americans to transmit their voices across vast distances. Meanwhile, Edison, embodying the virtues of Yankee ingenuity and rugged individualism, pioneered the practical use of electricity as an energy source. By the late 19th century, electricity illuminated America’s cities, powering factories, lighting homes, and forever changing urban life.

Corporate Dominance and Consolidation

The rise of corporations marked the industrial era. While inventors like Edison became iconic figures, the true victors of the age were the corporations that capitalized on their innovations. For example, by 1892, the electric industry had consolidated, sidelining Edison but solidifying corporate dominance in the burgeoning market. This era saw the transition from individual enterprise to massive corporate structures, reshaping the American economy.

Industrial Advancements and Speed

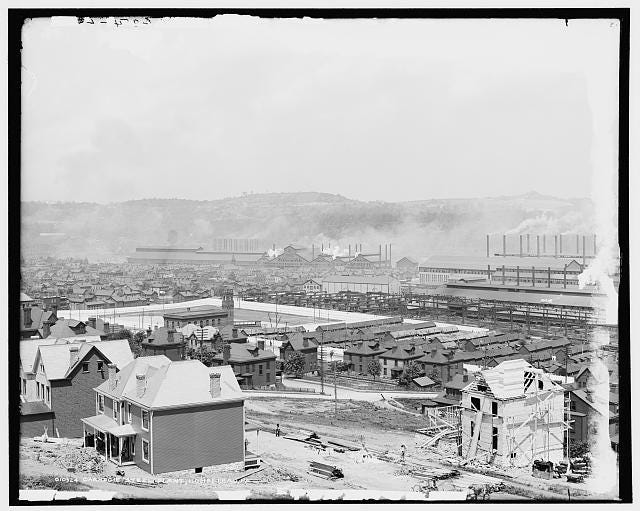

Advances in materials and manufacturing redefined productivity. The Bessemer Process, for instance, revolutionized steel production, reducing the time required to produce 3 to 5 tons of steel from days to mere minutes. Steam and electricity replaced human and animal muscle as primary energy sources, while iron gave way to steel as the foundation of industrial infrastructure.

"After the Civil War, two new processes allowed for the creation of furnaces large enough and hot enough to melt the wrought iron needed to produce large quantities of steel at increasingly cheaper prices. The Bessemer process, named for English inventor Henry Bessemer, and the open-hearth process, changed the way the United States produced steel and, in doing so, led the country into a new industrialized age." —Openstax

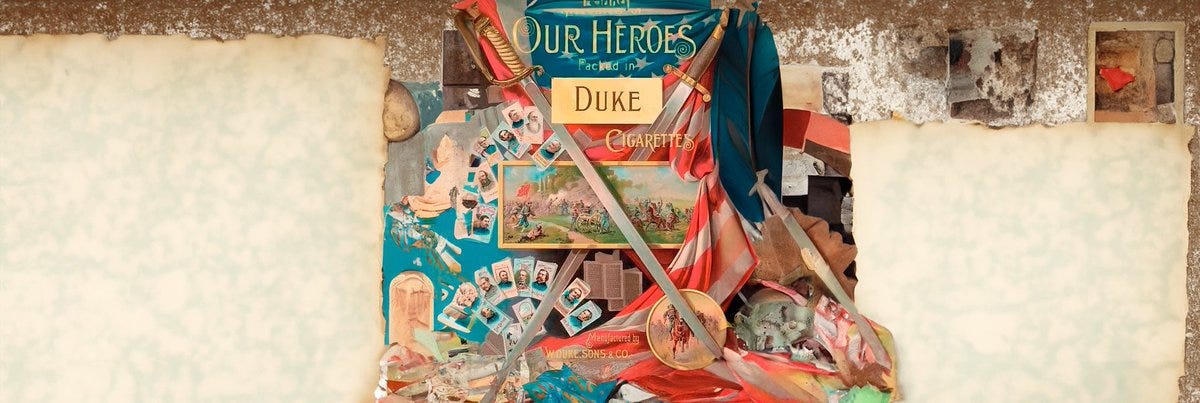

Tobacco, Oil, and Mechanized Innovation

James Duke harnessed new technology to reshape the tobacco industry. With a cigarette-rolling machine capable of producing 100,000 cigarettes per hour, Duke’s American Tobacco Company consolidated four major producers into a single, dominant enterprise by 1890. Similarly, oil became a vital resource, lubricating machines and providing light for homes, factories, and streets.

The era’s innovations extended to agriculture and transportation. Manufactured ice enabled the long-distance shipment of perishable goods, leading to the birth of the meatpacking industry. Mechanized farming equipment slashed labor demands, reducing the time to produce an acre of wheat from sixty-one hours in 1860 to just over three hours by 1900.

Urban Growth and Uneven Progress

The Industrial Revolution spurred massive urbanization. Between 1860 and 1914, New York City grew from 850,000 to over 4 million residents, Chicago surged from 110,000 to 2 million, and Philadelphia expanded from 650,000 to 1.5 million. While industrial and political elites orchestrated one of the most significant periods of economic growth in human history, their progress came at a cost. The labor force—comprising Black, white, Chinese, European immigrant, and female workers—bore the brunt of this transformation, enduring exploitation and inequitable treatment based on race, gender, nationality, and social class.

The industrial era solidified the United States as a global economic power but also exposed the tensions and inequalities that accompanied rapid growth, which would provide ample tinder for conflict in the 20th century. From the conquered plains of Native America to the bustling metropolises of the East Coast, the nation’s transformation was as complex as it was profound.

Ideas of the Era: Social Darwinism, Inequality, and the Role of Wealth

The late 19th century saw sweeping ideological shifts as America grappled with the rapid expansion of industrial capitalism and the social upheavals it brought. The philosophies of the era shaped these ideas, blending scientific interpretations with economic theories to justify extreme inequality, neglect of the poor, and the dominance of industrial magnates.

Drawing inspiration from Charles Darwin’s theories of natural selection, Social Darwinism equated the cutthroat competition of the marketplace with the processes observed in nature. Adherents like Herbert Spencer and William Graham Sumner, wealthy Anglo-Americans who saw themselves as biologically superior to other American groups, gave tinder to the political and social fires of the Gilded Age.

From their societal perch, they argued that social progress resulted from ruthless competition, where the weak inevitably perished, and only the fittest survived. This harsh worldview concluded that the suffering of the poor was not a moral failing of society but an essential step in evolution, strengthening the human species.

Industrialists seized upon this ideology, finding a convenient rationale for the burgeoning wealth gap. The idea that wealth equated to “fitness” and that the rich were inherently superior justified inequality and positioned efforts to help the poor as counterproductive, slowing progress. These concepts were central to defending Gilded Age economic practices and shaped the broader ethos of laissez-faire capitalism.

Social Darwinism and its focus on competition were often intertwined with ideas of racial superiority. Scientific racism, a pseudo-scientific doctrine, argued that certain races were inherently superior and that neglecting the poor could be seen as an act of racial progress. These beliefs were used to reinforce the dominance of Anglo-Saxon elites and maintain the status quo, perpetuating racial hierarchies and justifying the mistreatment of minority groups and the working poor.

Andrew Carnegie, a steel magnate and one of the era’s wealthiest figures, presented a counterpoint to the pure Social Darwinist approach with his 1889 essay, The Gospel of Wealth. While he embraced the idea that the accumulation of wealth was a sign of fitness, Carnegie argued that the rich bore a moral responsibility to use their fortunes for the betterment of society. He called upon industrialists to “administer surplus wealth for the good of the people” through philanthropy.

Carnegie's vision earned him public praise, with acts like funding public libraries and universities leaving a tangible legacy despite his years as a ruthless industrial titan. Yet his call to action inspired few among his peers, as many industrialists focused on maximizing profit rather than engaging in meaningful reform.

Social Darwinism also shaped government policy, mainly through the principle of laissez-faire economics. This approach maintained that the government should not regulate the economy, intervening only to protect private property. The belief that the economy operated under natural laws, much like evolution, rendered any interference—labor protections, taxation, or regulation—an unnatural disruption.

The Supreme Court, reflecting the dominant ideologies of the time, reinforced these economic principles. During the 1880s and 1890s, the Court consistently sided with big business, interpreting the 14th Amendment in ways that benefited corporations. By defining corporations as “persons,” the Court shielded them from certain forms of taxation and regulation while stifling efforts by labor organizations to improve working conditions.

These judicial actions protected the rights of industrial magnates like Carnegie and Jay Gould, often at the expense of workers. The Court’s inaction in promoting humane treatment allowed dangerous working conditions, exploitative wages, and labor strikes to define the industrial workforce of the Gilded Age.

The ideas of this era—Social Darwinism, scientific racism, laissez-faire economics, and judicial support for big business—combined to create a framework that perpetuated inequality and justified the vast power of the industrial elite. While figures like Carnegie advocated philanthropy, such voices were rare, and the policies and philosophies of the time entrenched the harsh realities of Gilded Age capitalism.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Corbett, P. Scott, Volker Janssen, John M. Lund, Todd Pfannestiel, Paul Vickery, and Sylvie Waskiewicz. U.S. History. Houston, TX: OpenStax, Rice University, 2014.

Locke, Joseph, and Ben Wright, eds. The American Yawp.

Schweikart, Larry, and Michael Allen. A Patriot's History of the United States: From Columbus's Great Discovery to the War on Terror. New York: Sentinel, 2004.

Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. New York: Harper & Row, 1980.