The Republican elephant as a symbol for the Grand Old Party (GOP) traces back to the turbulent political landscape of the post-Civil War era, a period marked by Reconstruction’s unraveling, economic upheaval, and anxieties over executive power. In the hands of Thomas Nast, the era’s preeminent political cartoonist for Harper’s Weekly, this emblem emerged not as a triumphant mascot but as a satirical commentary on partisan folly and media-driven panic.

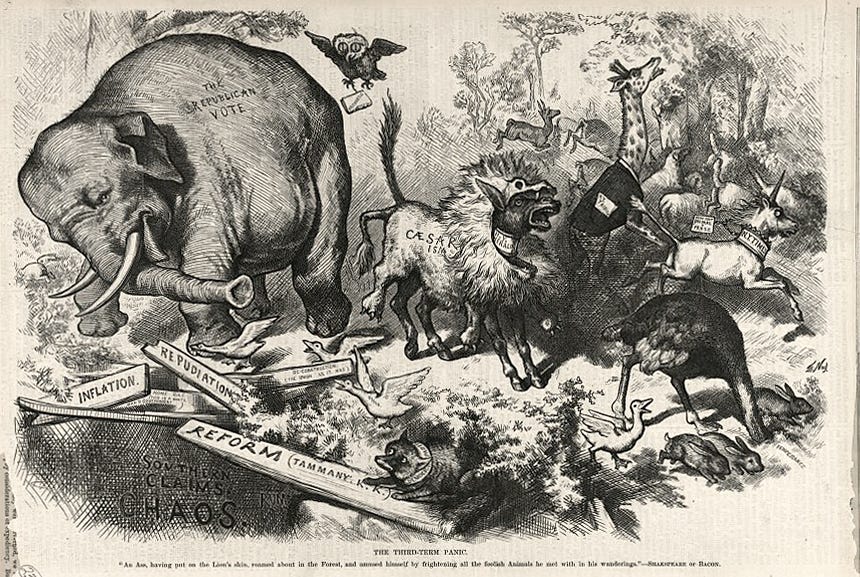

Nast, a German immigrant whose sharp pen had already skewered corruption in New York City’s Tammany Hall and championed causes like abolition and civil rights, wielded caricature as a tool to dissect the nation’s democratic experiment. Nast’s creation of the elephant in 1874 encapsulated the GOP’s vulnerabilities at a moment when the party, forged in the fires of antislavery activism, grappled with internal divisions and external threats. The elephant made its debut on November 7, 1874, in a Harper’s Weekly cartoon titled “The Third-Term Panic,” a pointed response to rumors swirling around President Ulysses S. Grant’s potential bid for an unprecedented third term—an idea Nast derided as “Caesarism,” evoking fears of imperial overreach in a young republic still haunted by the specter of monarchy.

The midterm elections that year had delivered a stinging rebuke to Republicans, with Democrats seizing control of the House of Representatives amid economic depression following the Panic of 1873 and widespread disillusionment with Grant’s administration scandals. Nast’s illustration captured this chaos through a menagerie of animals symbolizing newspapers, states, and political issues fleeing in terror. At the center lumbered the elephant, labeled “The Republican Vote,” stumbling toward a pitfall while alarmed by a donkey (representing the Democratic press) disguised in a lion’s skin marked “Caesarism.”

The donkey’s braying cry of imperial danger, Nast implied, was a false alarm designed to spook the GOP’s sturdy but skittish base. Drawing from Aesop’s Fables and contemporary circus imagery, the elephant embodied the party’s perceived bulk and strength—yet also its clumsiness and susceptibility to manipulation. This was no isolated whimsy. Nast’s symbols were rooted in the cultural currents of Gilded Age America, where visual metaphors bridged the gap between elite politics and an expanding electorate. The donkey, already loosely associated with Democrats since Andrew Jackson’s era, gained fixed form under Nast’s influence, but the elephant proved even more enduring.

In subsequent cartoons, Nast revisited the motif, portraying the elephant as battered yet resilient—trapped in pitfalls, plagued by “inflation” rags, or stampeded by reformist zeal. By the late 1870s, as the GOP navigated Rutherford B. Hayes’s contested 1876 POTUS victory and the end of Reconstruction, the symbol had permeated public discourse, appearing in rival publications and solidifying its place in American iconography. Critics like those at the New York Herald mocked Nast’s “wild animals” as overreach, but letters from admirers, including frontier officers and governors, attested to its resonance, praising depictions like the “Army Backbone” (pictured below) skeleton as exposés of military neglect.

Over time, the elephant transcended Nast’s satirical intent, evolving into a badge of GOP identity amid the party’s shift toward industrial capitalism and imperial expansion. By the turn of the century, it stood as a testament to how visual culture shaped political allegiance in an age of mass media, much as environmental forces molded the American West—a region Nast indirectly invoked through his critiques of frontier policy. Yet the birth of the elephant logo in 1874 reminds us of the fragility of symbols: born of defeat, not dominance, the Republican elephant endures as a wry emblem of a party’s capacity for both blunder and endurance in the grand narrative of American democracy.

Paine, Albert Bigelow. Th. Nast: His Period and His Pictures. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1904.