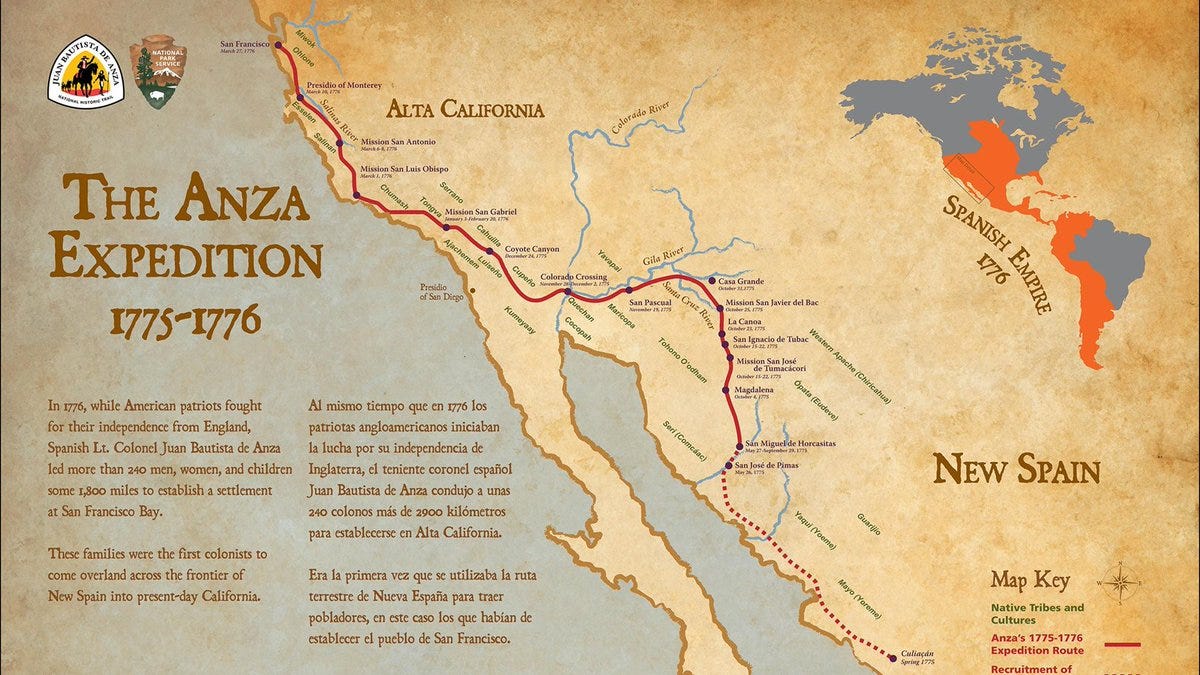

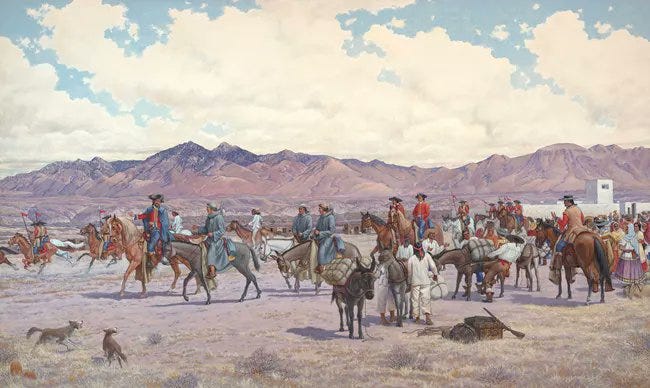

Juan Bautista de Anza’s second expedition to Alta California, launched on October 23, 1775, echoed the ambitions of his first journey but on a far grander scale. Departing from Tubac Presidio in what is now Santa Cruz County, Arizona, the expedition comprised 240 individuals: soldiers, colonists, families, and a substantial number of livestock. This ambitious undertaking aimed to establish new settlements and reinforce Spain’s fragile presence in the northern frontier.

Anza, promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel, led the group with unwavering determination. By his side were three Catholic priests—Pedro Font, Francisco Garcés, and Tomás Eixarch—who represented the spiritual arm of Spain’s colonization efforts. The expedition included ten veteran soldiers from Tubac, twenty new recruits from Sonora, twenty-nine wives of soldiers, 136 children, three vaqueros, twenty muleteers, and three Native interpreters. This diverse assembly underscored the multidimensional nature of Spain’s mission: to settle, defend, and evangelize.

Among the travelers was José María Pico, father of future California leader Andrés Pico, who would meet his future wife, María Eustaquia Gutiérrez, on this journey. Eustaquia, just four years old, traveled with her widowed mother, María Feliciana Arballo, and her six-year-old sister, Tomasa. Arballo had been recently widowed; her husband, Juan José Gutiérrez, was killed in a skirmish with Indigenous people only a month before the expedition’s departure.

The Gutiérrez-Arballo family represented a broader story of opportunity on the frontier. Classified as mulatos libres (free Afro-Europeans), they sought Alta California as a means of escaping the rigid Sistema de castas. This caste system dictated opportunities based on race and skin color in New Spain. While the caste system lingered on the frontier, its rules were more fluid, allowing social mobility through marriage, military service, and frontier settlement. This flexibility enabled Arballo’s daughter, Tomasa, to marry later, Juan José Sepúlveda, a prominent member of the Sepúlveda family of Villa Sinaloa. By the 1790 San Diego census, Tomasa, a child of mulatos libres, was recorded as Español (Spanish, or “white”) after her marriage to Sepúlveda. For families like the Gutiérrez-Arballos, the frontier offered a chance for survival and a path to redefine identity and status.

Arballo was the only widow permitted on the trip with her two young daughters, with Tomasa likely on the back of a saddle and Eustaquia wrapped closely to her body. Familial connections may have facilitated Arballo’s participation in the expedition—Ygnacio María Gutiérrez, perhaps a relative of her late husband, or by Anza’s empathy, having lost his own father in a similar type of conflict. Regardless, the family joined the venture with their eyes on the ultimate goal: to help colonize Alta California, specifically San Francisco.

By November 4, 1775, the expedition reached the Gila River crossing, where Chief Salvador Palma once again welcomed Anza at his rancheríaat San Dionisio. Chief Palma and the Yuma people played a pivotal role in the journey as they had done the prior, constructing tule rafts to ferry Anza’s large caravan and livestock across the Colorado River. Their assistance underscored the importance of Indigenous alliances in navigating the harsh frontier.

From December 12 to 19, the expedition endured a grueling stretch through the Colorado Desert. Winter brought extreme cold, compounding the scarcity of water and the challenges of the terrain. These hardships slowed progress and tested the resilience of the travelers. Yet, the journey pressed onward, propelled by Anza’s leadership and the collective resolve of the group, as they edged closer to their destination and the promise of Alta California.

As the Anza expedition made camp on December 17, 1775, at Ranchería de San Sebastian, the settlers seized a rare opportunity for joy amidst the hardships of their journey. That evening, a lively fandango brought the group together in celebration. Music and dance, the cultural lifeblood of the settlers, offered a brief reprieve from the punishing terrain and cold desert nights. Among the revelers was María Feliciana Arballo, the widowed mother of two young daughters, whose exuberance and spirited behavior did not go unnoticed.

Arballo’s conduct, while likely a source of admiration or amusement to many of her fellow travelers, scandalized Catalan Franciscan Friar Pedro Font. In his diary, Font expressed shock at what he perceived as her inappropriate behavior. His disapproval reflected the austere moral expectations of the Church and the friar’s discomfort with the relaxed social boundaries that emerged in the liminal space of the frontier. Font’s observations, later highlighted by historian Herbert Eugene Bolton, sharply contrast the disciplined order sought by the Franciscan missionaries and the vibrant, unrestrained humanity of the settlers themselves,

“At night with the joy at the arrival of all the people, they held a fandango. It was somewhat discordant, and a very bold widow who came with the expedition sang some verses which were not at all nice, applauded and cheered by all the crowd. The sweetheart of the naughty widow proceeded to remonstrate with her. Anza, hearing the row, sallied forth from his tent and reprimanded the man for chastising the woman. Father Font put in, ‘Leave him alone, Sir, he is doing just right.’ ‘No, Father,’ said Anza, ‘I cannot permit such excesses when I am present.’ Font comments hereupon, ‘He guarded against the excesses, indeed, but not against the scandal of the fandango, which lasted until very late.’ Next morning after Mass Font ‘spoke a few words' about the last night's dance, telling the people that instead of holding such festivities in honor of the Devil they should have been thanking God for sparing their lives.”

After leaving Ranchería de San Sebastian, Anza and his expedition again found themselves in Coyote Canyon, where they celebrated Christmas 1775. Once again, the mountain-dwelling Serrano people and the Yuma, whose longstanding enmity had carved a bitter divide, encountered one another during Anza’s expedition. Of course, the Serrano nor the Yuma were called by their Spanish name. Instead, they were called Jahueches, or Caguenches and Ajagueches. Their rivalry, rooted in territorial disputes and cultural differences, had long been a source of regional conflict. The tension between these two groups was palpable, and the delicate peace that Anza had previously brokered was tested as they met again.

Aware of their relationship's fragile nature, Anza sought to reaffirm the tenuous alliance established during his earlier journey. His leadership relied on diplomacy and a keen understanding of the mutual benefits that peace could bring to all parties involved. The meeting served as a reminder of the complexities of frontier dynamics, where survival often demanded cooperation, even among historical adversaries. For the Serrano and Yuma, this renewed encounter under Anza’s watchful eye was another step in the uneasy dance between reconciliation and the persistence of old hostilities. Anza later wrote,

“To defuse the tension, I gathered the group and made an appeal for peace. Addressing the assembled tribesmen, I explained the benefits of harmony and friendship. The most significant moment occurred when I instructed the Yumas and their erstwhile rivals to embrace each other in the presence of the assembly. This act, unprecedented among these communities, was met with cheers and visible relief.”

His words carried the authority of a mediator, and he orchestrated a symbolic act of reconciliation: the Serrano chief and two Yuma representatives were brought together to embrace a gesture of unity. The Serrano, long burdened by fear of the Yuma’s formidable martial reputation, reacted with palpable relief and joy to Anza’s efforts at reconciliation. The ceremonial breaking of arrows—an ancient and powerful ritual symbolizing the end of hostilities—was performed to the cheers and approval of both groups. This symbolic act marked the cessation of their enmity and transformed the gathering atmosphere into mutual respect and camaraderie—at least for one night.

On December 26, 1775, as the expedition traversed the San Gorgonio Pass, they were met with a fierce storm—a lashing mixture of snow, hail, and rain—that compounded the hardship of their dwindling water supply. Forced to dig makeshift wells, their efforts yielded little relief, resulting in the loss of some hundred head of livestock. Yet, despite these adversities, Anza and his company demonstrated remarkable composure, enduring the ordeal with calm patience and steadfast resolve. Despite the physical hardships wrought by nature, the spiritual mission of the expedition remained undeterred, as exemplified by Father Francisco Garcés, whose zeal for conversion found expression in a powerful visual tool during their passage between Santa Olaya and the mouth of the Colorado River.

In the winter months of December 1775 to January 1776, Father Francisco Garcés carried with him a painted banner designed to captivate and convert. On one side, it depicted the Virgin Mary in serene grace, cradling the Christ child; on the other, a tormented soul engulfed in the flames of hell. The contrasting images were meant to evoke both reverence and fear, a visual sermon for the Indigenous peoples encountered along the way.

The reactions to the banner were stark and telling. The Native onlookers gazed with evident pleasure at the image of the Virgin, declaring her muy buena—“very good.” Her calm, maternal presence seemed to resonate universally. Yet, upon seeing the agonized figure on the reverse side, they recoiled in visible horror. This visceral reaction delighted Father Garcés, who interpreted it as evidence of their spiritual readiness and openness to salvation. For the friar, such moments reinforced his belief in the providential mission of the Church and the inevitability of the Natives’ conversion to Christianity.

To Garcés, these reactions were not merely encouraging—they were affirmations of his evangelical purpose, signs that the Indigenous peoples, though unbaptized, were preordained for spiritual redemption. The juxtaposition of reverence for the Virgin and fear of damnation was a narrative that aligned perfectly with his vision of the frontier as fertile ground for both missionary zeal and imperial ambition.

On the first day of the New Year in 1776, Anza’s expedition resumed its journey along the River Santa Ana. By January 4, the group reached Mission San Gabriel, a settlement that stood as a beacon of what the Spaniards envisioned a mission should be. With its abundant resources, fertile fields, and sturdy structures, San Gabriel symbolized spiritual and economic stability—a hard-won stronghold that reflected the dedication of its residents.

For María Feliciana Arballo and her two daughters, however, Mission San Gabriel marked the conclusion of their journey with the Anza expedition. Arballo had fallen in love with Juan Francisco López, a soldier stationed with the mission guard. Her decision to remain was likely influenced by a combination of factors: the stability San Gabriel seemed to offer, the prospect of a secure life as the wife of a soldier, and perhaps lingering embarrassment over the fandango incident weeks earlier. Whatever her reasons, she chose to stay, and records show that she married López on March 6, 1776. This union began her second family, and she would eventually have six or more children.

Following López’s death in 1800, Arballo married Mariano Tenorio at Mission San Diego later that same year, further intertwining her life with the fabric of Alta California. The interconnectedness of early Californian families—born of necessity in small, tight-knit communities—meant that Arballo’s lineage would leave a lasting legacy. Through her daughters, Tomasa and Eustaquia, she created ties to two of the region’s most prominent families: the Picos and the Sepúlvedas. These alliances exemplified how Alta California evolved from a European outpost into a dynamic melting pot where Native, African, European, and Asian bloodlines intermingled, shaping the region’s identity.

If Anza expected his fellow Spaniards to greet his efforts with the same openness and hospitality he extended to others, he was sorely mistaken. Upon receiving correspondence from Fernando Javier de Rivera y Moncada (1725–1781), a prominent Spanish military officer and administrator, Anza encountered a colder and more pragmatic response. Rivera, a central figure in Alta California’s early colonial history, was no stranger to diplomacy, command, and the intricacies of managing Spain’s fragile foothold in the Americas. Yet his communication with Anza reflected the complexities of colonial hierarchy and the tension inherent in overlapping spheres of authority.

Rivera had built his career on competence and loyalty, steadily rising through the military ranks. Like Anza, he was connected to prominent Spanish settler families and shared a reputation for diligence and strategic acumen. As Captain of the Presidio of Loreto in Baja, California, around 1768, Rivera’s timing aligned perfectly with the broader expansionist ambitions of Spain in the region. His position brought him into close collaboration with Gaspar de Portolá, Alta California’s first governor, providing Rivera with an opportunity to shape the logistical underpinnings of Spain’s northernmost colonial efforts.

Rivera played a key role in Portolá’s early expeditions, including exploring San Diego and Monterey, where Spanish presence was solidified through presidios and missions. Rivera would later succeed Portolá as military governor of Alta California in 1774, managing the territory’s entire operation. His work laid foundational stones for Spain’s expansion in Alta California, securing his legacy as a critical figure in the region’s colonial history. However, his correspondence with Anza reflected not camaraderie but skepticism, a reminder of the competing ambitions and territorial sensitivities that oft-defined interactions among Spain’s frontier leaders. For Anza, Rivera’s guarded approach was a sobering reflection of the challenges of navigating Native diplomacy and colonial politics in Alta California.

The relationship between Rivera and Anza was marked by professional competition and a lack of direct communication. Both men relied heavily on messengers and written correspondence, often leading to misinterpretations and sowing the seeds of mutual distrust. These indirect exchanges only exacerbated the tension between two leaders navigating the complexities of colonial governance and expansion. When Rivera and Anza did meet face-to-face, their interactions were fraught with visible strain. One observer noted Rivera’s “visible rage” and uncharacteristic behavior during one such encounter, underscoring the deep undercurrent of hostility. Rivera’s notoriously fiery temper effectively undermined any opportunity for meaningful dialogue, which had proven a stumbling block in his dealings with Anza and many others who crossed his path. Rivera’s combative disposition made cooperation difficult, further complicating the already delicate leadership dynamics in Alta California’s precarious frontier environment.

After departing from San Gabriel, Anza’s expedition pressed northward, ultimately arriving at the Royal Presidio of Monterey on Sunday, March 10, 1776, at precisely 4:30 PM. The journey had been monumental—162 days since departing Horcasitas and spanning 316 leagues from Tubac. Their arrival marked the culmination of months of hardship and discovery, a triumph of endurance and leadership.

Father Pedro Font, the expedition’s chronicler, captured the moment with his characteristic flair for detail. In his diary, Font painted a vivid picture of the procession approaching the presidio.

“When we arrived at the presidio, everybody was overjoyed, in spite of the fact we were so wet, for we did not have a dry garment. We were welcomed by three volleys of the artillery, consisting of some small cannons that are there, and the firing of muskets by the soldiers.”

The Presidio’s buildings formed a modest but purposeful square, each side reflecting the rhythms and priorities of colonial life. On one side stood the commander’s residence, a simple yet commanding structure, adjacent to the storehouse where the storekeeper made his home. Opposite this was a humble chapel, its walls bearing the weight of both spiritual hope and the toil of its builders, flanked by the soldiers’ quarters—a no-frills barracks brimming with the tools of defense and survival. Completing the square, the remaining sides were lined with small huts and homes, shelters for the families and laborers whose lives intertwined with the presidio’s mission. Together, these structures embodied a rugged practicality, the heart of a fragile outpost standing firm against the vast wilderness beyond.

On March 27, 1776, Juan Bautista de Anza’s expedition paused to make camp near what is now known as Mountain Lake. At the time, the Spaniards gave the lake no name, though they referred to its outlet as Arroyo del Puerto—what we know today as Lobos Creek. The group arrived late in the morning, around 11 a.m., and wasted no time setting up camp. Anza, ever restless and forward-looking, spent the afternoon exploring the surrounding terrain. His reconnaissance took him westward and southward, where he sought the essentials for his proposed fort: water, pasture, wood, and timber. He found all but the last.

Retracing his steps to the spring and rivulet discovered the previous day, Anza named the waterway Arroyo de los Dolores, after the last Friday in Lent. Anza’s name and location choice would later become the site of Mission Dolores. His party pressed on, circling the hills and crossing an earlier trail into the Cañada de San Andres, a glen rich with timber. The expedition ventured far enough to encounter the San Mateo Creek flowing into the plain, where they felled a large bear. Crossing the low hills, they returned northward, their observations setting the foundation for the presidio Anza envisioned.

The following day, Anza, accompanied by the priests, ventured to what we now call Fort Point. It was, as he noted, uncharted territory—“where nobody had been.” There, standing on the tableland that overlooked the Golden Gate, Anza erected a cross and buried an account of his explorations at its base. At that moment, he declared this windswept bluff as the future site of the presidio. It was a deliberate choice, blending practicality with a vision: a place that would command the bay and assert Spain’s claim to Alta California, a cornerstone of an empire carved into the edge of the Pacific.

Rivera’s resistance to Anza’s plans for the presidio at San Francisco became a masterclass in bureaucratic obstruction. Rather than outright defiance, Rivera relied on delays and vague objections to stall progress. His correspondence with the viceroy was littered with evasions, carefully crafted to give the appearance of compliance while subtly undermining Anza’s efforts. By refusing to authorize the necessary arrangements, Rivera wielded inertia as a weapon, ensuring that the foundation of the San Francisco Presidio languished in uncertainty. His actions revealed a personal disdain for Anza and the intricate power struggles that defined colonial governance, where ambition and rivalry often eclipsed the broader goals of the empire. Although Rivera attempted to stall the presidio’s development, Anza’s recommendations were implemented, and construction began under José Joaquín Moraga, Anza’s subordinate, in 1776.

There were many conflicts in Rivera’s life, many more to be covered, but his final conflict was with the Yuma, the same people who were so friendly and hospitable to Anza a few years earlier. By late June 1781, Captain Fernando Rivera y Moncada, a seasoned but increasingly irascible figure in Spanish colonial history, arrived at the Colorado River settlements with a party of about forty soldiers and their families. These settlements—San Pedro y San Pablo de Bicuner and La Purísima Concepción—had been established as strategic Spanish outposts to protect the Anza trail, blending features of missions, presidios, and pueblos.

These outposts aimed to secure Spain’s fragile claim to the Colorado River corridor and support overland routes to Alta California. Yet the Spaniards’ presence strained the once-friendly relations with the Yuma people, whose resources and livelihoods were severely impacted. The Spaniards’ livestock devastated the mesquite fields, a critical source of sustenance for the Yuma. At the same time, Rivera’s failure to offer gifts or show customary deference to Indigenous leaders further deepened resentment.

On the morning of July 17, 1781, tensions exploded into violence. The Yuma launched a coordinated attack on the San Pedro y San Pablo outposts. The assault was swift and deadly, claiming the lives of Fathers José Matías Moreno and Juan Díaz, as well as Sergeant Vega and most of the settlers and soldiers stationed there. The Yuma spared few, and those who survived were taken captive. The next day, the Yuma crossed the river and overwhelmed Rivera’s camp, where he and the remaining soldiers had hastily thrown together makeshift defenses. Despite their efforts, the Spaniards were vastly outnumbered. The soldiers fell to the Yuma’s arrows and clubs one by one. Among the casualties was Rivera himself, whose long and prominent career in Alta California’s colonial history ended in chaotic bloodshed. Women and children were mostly spared but taken captive, leaving the settlements and camps decimated.

On the same day, a similar fate befell the settlement of La Purísima Concepción. As Father Francisco Garcés said Mass, Yuma warriors stormed the town. Commandant Islas and a corporal, the only soldiers present, were among the first to be killed, followed by most of the unarmed men scattered in nearby fields. In total, around fifty Spaniards, including thirty soldiers and four priests, lost their lives in the attacks on July 17 and 18. The Yuma victory was catastrophic for Spanish ambitions in the region, marking the effective end of their plans for the Colorado River corridor for decades. Though some captives were ransomed, the event closed land travel and communication from New Spain to Alta California until the 1820s. Rivera, whose obstinate leadership had alienated the Yuma, left a cautionary legacy in Alta California’s history.

After successfully completing his second expedition to Alta California in 1776, Juan Bautista de Anza continued his dedicated service to the Spanish Crown, though his career shifted away from the region he had so profoundly influenced. Anza’s return to Tubac Presidio on May 26, 1776, marked the official conclusion of his journey to lay the foundations for San Francisco’s presidio and mission. Though he did not witness the physical construction of these settlements, his careful planning and leadership ensured their eventual success, solidifying Spain’s presence in the northern frontier of Alta California.

In 1777, Anza was appointed governor of New Mexico, a role he held until 1787. As governor, he confronted the region’s challenges with the same determination that had defined his earlier expeditions. Anza sought stability through both diplomacy and force, mediating conflicts with Native American groups while launching decisive military campaigns, most notably against the Comanche. His efforts in New Mexico strengthened Spanish control and brought peace to the volatile frontier.

Anza’s life ended in Arizpe, Sonora, on December 19, 1788, at 52. His death marked the close of a storied career that left an indelible mark on the Spanish colonization of the Southwest and California. Anza’s expeditions are celebrated for establishing a viable overland route to Alta California, paving the way for settlements such as San Francisco and fostering connections across vast and rugged territories. Today, Anza’s legacy symbolizes leadership, vision, and perseverance. His contributions are commemorated through landmarks like the Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail, which honors the route he charted and the communities he helped establish. Anza’s name remains etched in the history of California and the American Southwest, a testament to his pivotal role in shaping the region.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of California. Vol. 1, 1542–1800. Vol. 18 of The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft. San Francisco: The History Company, 1884.

Bolton, Herbert Eugene. Anza’s California Expeditions. Vols. 1, 2, and 4. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1930.

Cherny, Robert W., Gretchen Lemke-Santangelo, and Richard Griswold del Castillo. Competing Visions: A History of California. 2nd ed. Boston: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning, 2014.

Guinn, J. M. El Camino Real. Los Angeles: Self-Published, 1906.

Rawls, James J., and Walton Bean. California: An Interpretive History. 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011.

Smestad, Greg Bernal-Mendoza. A Guide to the Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail. San Francisco: Los Californianos, 2005.

Tyler, Helen. “The Family of Pico.” The Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly 35, no. 3 (1953): 222–223.