In the Spring of 1886, trouble was brewing along the vast iron veins of the American Southwest. For years, Jay Gould had been building his empire, acquiring railroads with a shrewdness that made him one of the most powerful men in the country—and one of the most despised. To him, railroads were more than just a business; they were an instrument of power, a way to control commerce, bend markets to his will, and keep competitors at bay, but they were something else entirely for the thousands of men who worked the yards, repaired the tracks, and kept the trains running on time. The railroads were their livelihood, their connection to an economy that increasingly seemed only to benefit men like Gould.

The trouble began in March. The Texas and Pacific Railroad, one of Gould’s many holdings, had fired a group of unionized shop workers. It was not the first time railroad laborers had been dismissed for organizing, nor would it be the last. This time, the Knights of Labor, the largest and most influential union of its day, decided they would not stand for it. They called a strike, and within weeks, it spread like wildfire across the Missouri Pacific Railroad, another Gould-controlled line, bringing train traffic in Texas, Arkansas, and Missouri to a standstill. For Gould, who had faced labor unrest before, it was merely another test of wills. He had long believed that industrial disputes could be managed like any other business challenge—with calculation, resources, and, if necessary, force. His confidence was not misplaced.

The railroads, after all, were his property, and he had the money and the influence to protect them. This was no ordinary labor stoppage, as the strikers, whose ranks were swelling daily, had the support of their communities. In Fort Worth, St. Louis, and Marshall, Texas, the rail yards fell silent, and crowds gathered to protest, some carrying signs, others simply watching and waiting. For the moment, public sympathy was on their side. Gould, however, was unmoved. He called in private security forces and local militias to break the strike.

In Marshall, the Texas governor dispatched the state militia, a show of force meant to intimidate, though it only hardened the resolve of many. In Fort Worth and St. Louis, armed guards clashed with striking workers. Shots were fired. Some never made it home. The violence shocked the nation. Newspapers reported on the bloodshed, on the men killed in the name of keeping the trains running. Still, Gould did not waver. His strategy was simple: wait them out. The strike, for all its energy, had a fatal weakness—momentum was hard to sustain, and without a steady flow of wages, the workers would eventually be forced to return.

By late spring, that moment arrived. The strike collapsed. The Knights of Labor, unable to maintain pressure, suffered a blow from which they would never fully recover. The Missouri Pacific and Texas & Pacific rolled on, as Gould had always known they would. The scars remained for workers who had risked everything for better wages and conditions and found themselves blacklisted. Towns that had witnessed violence in the name of progress carried the memory long after the trains were moving again.

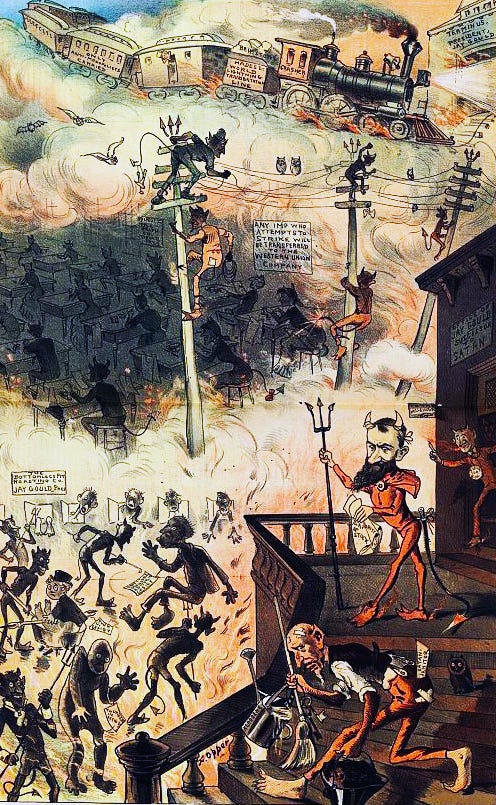

And Gould—more affluent, more powerful than before—became, in the eyes of many, the embodiment of unchecked capitalism in an era that increasingly seemed to belong to men like him. The Southwest Railroad Strike of 1886 was more than just a labor dispute. It was a battle in the growing war between industrialists and workers, between those who controlled the machines and kept them running. For Jay Gould, it was just another contest—and one that, as usual, he had won at a cost that went beyond dollars and cents.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Henry Davenport Northrop, Life and Achievements of Jay Gould, the Wizard of Wall Street (Bridgeport, CT: Union Book Company, 1892), 122-126.