In the dim light of a November dawn in 1775, the mission of San Diego awoke to a nightmare. Flames licked the wooden beams, and the air filled with the war cries of Kumeyaay warriors—eight hundred strong, descending from the shadowed hills like a storm unleashed. Francisco Palóu, disciple and chronicler of the Venerable Father Junípero Serra, stood far from that fiery chaos. Yet, its echoes reached in the quietude of Monterey, where Palóu penned the trials of what he believed to be a sacred endeavor.

The mission system, the grand chain of faith stretching from San Diego to San Francisco, was to Palóu and others a labor of love, a vineyard of the Lord. But on that fateful night, it became a crucible of rebellion, testing the resolve of Padres, soldiers, and Indians alike. This is the tale of those turbulent years of Palóu's life, a story of divine purpose clashing with human fury, as seen through the eyes of one who walked beside Serra, bearing witness to the triumphs and tragedies of Alta California.

The Sacred Vision and the Savage Land

One must first grasp the vision that drove Palóu and the other Catholic clergy to understand the rebellions. Junípero Serra, Palóu's revered teacher, arrived in the untamed land of Alta California in 1769 at the age of fifty-five, a man frail in body but aflame with zeal. Born in Mallorca in 1713, he had forsaken a professorship in philosophy for the missionary’s cross, believing martyrdom to be “the true gold and silver.”

His foot, swollen from an insect bite sustained on a 200-mile trek from Vera Cruz to Mexico City, never healed—an affliction he deemed a blessing, a mark of his sacrifice. To Serra, Palóu, and the others who followed, the Indians of California were lost sheep, souls yearning for the light of Christ. Under Serra's presidency, the “Sacred Expedition” of 1769 aimed to plant nine beacons of salvation missions amid a wilderness teeming with thousands of natives. By 1821, numbers would dwindle rapidly, a testament to the harsh toll of the Spanish presence.

To understand Palóu and his fellow Padres, it is crucial to note that they saw the Indians through the lens of their faith. To Serra, they were children of God, capable of redemption yet steeped in pagan darkness. In Serra's mission, Palóu, Serra's biographer, recorded his conviction that missionaries “should be able to punish their sons, the Indians, with blows”—a stern love meant to guide them to virtue. This would lead to conflict between the Native Californians, clergy, soldiers, and civil war within each of these groups.

Father Luis Jayme, stationed at San Diego, offered a gentler view, noting in his letters their adherence to natural law: “They do not have idols; they do not go on drinking sprees; they do not marry relatives, and they have but one wife.” He saw in them a logic, an alertness, a moral fiber rivaling that of many Christians. Yet, he lamented their resistance, puzzled that they did not immediately embrace a faith whose bearers arrived diseased and dying, as the Portolá-Serra expedition had in 1769, their crews ravaged by scurvy.

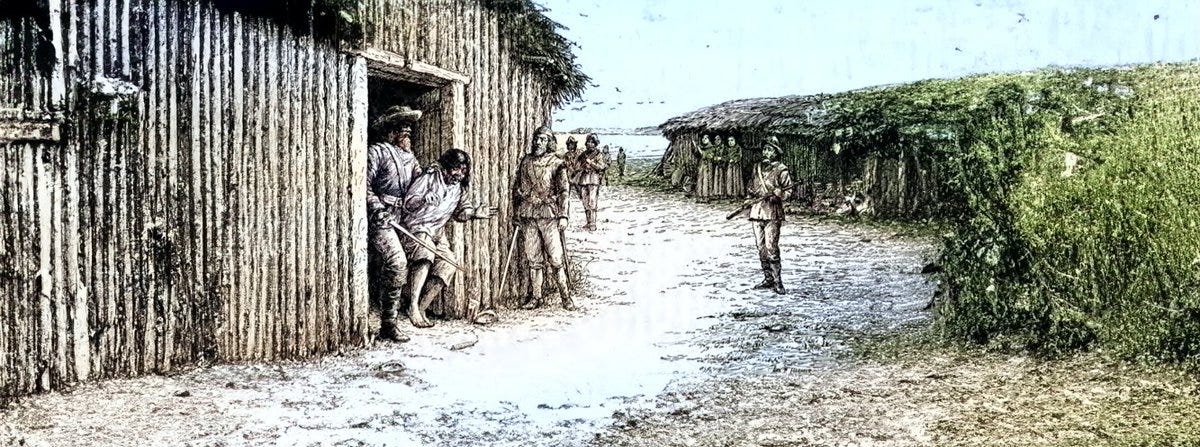

The soldiers, however, saw a different picture. Men like Fernando Rivera y Moncada, the leather-jacketed Soldado de Cuera, viewed the Indians as a threat to be subdued. Rivera, praised by Father Juan Crespí as one of “the finest horsemen in the world,” wore his rank in the colored stitching of his vest, his leather armor a shield against Indian arrows. To him, the Kumeyaay and others were savages—well-built, numerous, and prone to violence, as Crespí had observed. Their immediate hostility, perhaps seeded by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo’s fleeting visit in 1542, fueled a soldierly disdain. Where Palóu and his men sought conversion, their priors, some clergy, and soldiers sought control, their muskets and whips a language of dominance.

The Indians, the Kumeyaay, the Ohlone, the Costanoan, lived in a world upended. Their rancherías, clusters of life nestled along rivers and coasts, pulsed with traditions we aimed to supplant. To them, Catholic crosses and bells were not symbols of salvation but harbingers of loss—loss of liberty, land, and kin. The mission, with its promise of eternal life, demanded they abandon their past, their marriages reshaped by Christian rites, their bodies bent to labor under the Padres’ watchful eyes. It was a bitter bargain that they would resist with fire and blood.

The Flames of San Diego: November 4, 1775

The first great rebellion erupted at San Diego, a mission Palóu chronicled with a heavy heart in Serra’s biography. On October 4, 1775, Fathers Jayme and Vicente Fuster had baptized sixty new converts, some against their will—a triumph of grace, the clergy thought. But two fled, their hearts unyielding, and they rallied their kin in the shadows of the hills. Father Luis Jayme, a thirty-five-year-old Mallorcan priest stationed at Mission San Diego, wielded a stern hand against the Indians under his care. This practice fueled their deep resentment and ultimately led to his brutal demise.

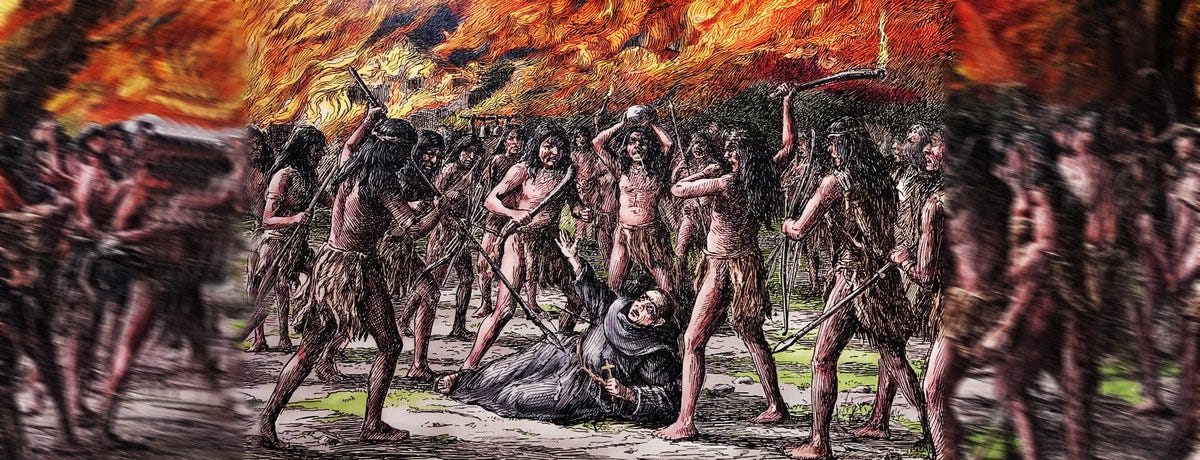

A month later, the two Kumeyaay who fled returned on November 4, along with eight hundred Kumeyaay descended upon the mission, their stealth a silent thunder stole down from the shadowed hills above Mission San Diego, their footsteps muffled by the earth, their intent as sharp as the arrows they bore. Father Luis Jayme, roused from sleep by the crackle of flames, could not have foreseen how fate had conspired to leave him vulnerable, for the soldiers who might have stood as sentinels were absent, drawn away by a grander design unfolding miles to the north.

On that very eve, Lieutenant José Francisco Ortega and his leather-clad troop had ridden out, their muskets slung and spirits high, to attend the founding of Mission San Juan Capistrano—a new beacon in the chain of faith Junípero Serra dreamed would bind this wild land to heaven. The mission at San Diego, stripped of its guard, lay open like a lamb before wolves; the presidio slumbered, its watchmen deaf to the rising tumult. Thus, the Kumeyaay struck, their war cries shattering the night, their torches turning the mission to ash, and Jayme’s pleas—“Love God, my children!”—lost in the chaos of a rebellion born of absence and outrage.

But love met fury. The warriors stripped him, dragged him to a creek, and beat him with stones, sticks, and a battle axe. Eighteen arrows pierced his flesh, his skull crushed by a stone—a martyrdom that echoed the saints he so admired. Palóu wrote of this, his pen likely trembling with sorrow: “The Indians let out their war cry… until his naked body reached the creek… unrecognizable.” The four soldiers who were left fought valiantly, one falling. Father Fuster and two boys loaded their guns in desperate defense. The presidio, a mere stone’s throw away, slept through the chaos, its guards oblivious until dawn revealed the smoldering ruin.

Why did they rebel? From Palóu's vantage, it was a rejection of the cross they bore. Serra had warned in Baja California, as Palóu recorded, that “the poor gentiles, until now as gentle as sheep, will turn on us like tigers.” Jayme hinted at their reasoning before his death: “They did not know why [the Spaniards] had come, unless they intended to take their lands away from them.” The soldiers’ sins—rape and violence—fueled this fire. Jayme wept at the example set by Christians, writing, “These gentiles were setting an example for us.” For the Kumeyaay, the mission was a prison, its whips and forced baptisms a betrayal of their freedom. The soldiers saw it as treachery, a savage uprising against order, Rivera later noting their “close intercourse with the pagan Indians” as a root of unrest.

Catholic principles guided the Church's response. Serra, upon hearing the news in Monterey, mourned Jayme as a martyr, his death a sacrifice for the faith. They sought to rebuild the mission and the shattered trust. Yet Rivera, arriving on January 2, 1776, with news traveling the 470 miles slowly, chose retribution. Calling on Juan Bautista de Anza, he mustered twenty-seven men, including Father Pedro Font, and reached San Diego by January 10.

Five chiefs were imprisoned, two flogged with such severity that one died—a punishment Father Pedro Font described with unease. Carlos, a leader in the rebellion, sought sanctuary in a warehouse-turned-chapel. Rivera, defying the sacred law of asylum, dragged him forth for punishment, leading to Rivera's excommunication by Fathers Fuster, Fermín de Lasuén, and Gregorio Antonio de Amurrio for his sacrilege. In a letter Father Palóu preserved, Serra insisted that Rivera seek forgiveness, a nod to the principle of reconciliation. However, the clash between Padre and the soldier widened the gulf between the Indians and the Spanish.

By 1784, when Serra breathed his last at Mission San Carlos, nine missions stood as monuments to his toil. Palóu succeeded him briefly, then Fermín Francisco de Lasuén doubled their number to eighteen by 1803, swelling the neophyte ranks to twenty thousand. Yet the rebellions lingered, echoes of a struggle unresolved. Palóu, penning his works in Mexico, reflected on Serra’s dying plea: “Let us now go to rest.” Palóu piously believed his rest was heaven’s, but for the Indians, rest remained elusive.

Mission life was a tapestry woven with threads of faith and fury. Missionaries built their days around the Doctrina—prayers memorized, hymns sung, lessons taught in the shadow of the cross. San Diego, rebuilt after 1775, hummed with activity: neophytes tilling fields, women spinning wool under Spanish wives’ tutelage. San Carlos was Palóu's heaven, its chapel a sanctuary of hope. Yet beneath this order lay a restlessness, a tension palpable in every lash, every flight.

The soldiers lived apart, their presidios a bulwark against the wild. Rivera’s men, superb on horseback, patrolled with muskets slung, their leather armor a constant reminder of their role. They ate the king’s bread, as Crespí praised, but their hands were swift to punish, their eyes blind to the Indians’ plight. Font’s candid words in 1776—“few Indians live there… more pagan than Christian”—revealed a mission struggling to hold its flock.

The Quiroste’s Cry: December 14, 1793

Eighteen years later, another torch flared at Mission Santa Cruz. On December 14, 1793, Quiroste warriors of the Ohlone people from a village near Año Nuevo struck with calculated fury. The mission, nestled among redwoods, was partially burned, its defenders caught off guard. The Quiroste, like the Kumeyaay, saw the mission as an invader, its bells tolling over lands once theirs.

To the Padres, the Ohlone were a challenge and a promise. Crespí, in his diaries, called them “the most savage” alongside the San Diegans, yet the Padres believed their souls were ripe for harvest. Serra’s vision, which was championed well after his death, held that discipline—sometimes harsh—was a father’s duty, a means to lift them from barbarism. But the Quiroste saw no salvation in their hymns. Their rebellion sprang from the same soil as San Diego’s: the loss of liberty, the weight of labor, the lash of the Padres’ whips. The mission’s demand to “marry as Christians,” as Catholic Doctrina instructed, tore at their social fabric, replacing kin ties with foreign rites.

Soldiers viewed this as defiance, a threat to the fragile order of Alta California. Governor Diego de Borica, in office since 1794, had decried the “deplorable condition of the Indians,” noting their cruel treatment. Yet his men, clad in leather, met resistance with force, their muskets a blunt answer to arrows and fire. The Quiroste, for their part, fought to reclaim a world slipping away, their attack a desperate howl against the mission’s unyielding grip.

Catholic principles here faltered in practice, though not in intent. The Doctrina, penned at Santa Barbara in 1798 by Father Cortés, taught, “There is only one true God… You suffered and died for me nailed to the Cross.” The Padres aimed to instill this truth as they saw fit, to offer eternal life through penance and prayer. But the Quiroste’s fire rejected that gift, a judgment many clergy pondered with sorrow. Serra, were he alive, would have seen it as a call to redouble their efforts, to win them with love—as he had urged me to record in his dying words: “I offer my own [blood]… for the reduction and conversion of one single soul.”

The Poisoned Soup: November 1811

A subtler rebellion simmered at Mission San Diego in November 1811. Father José Panto, retiring for the evening, sipped his soup and recoiled at its bitter, spicy taste, a white powder clouding the broth. Vomiting for a “very long half hour,” he summoned Corporal Antonio Guillen and Sergeant Mariano Mercado, who confirmed the poison. The perpetrator was Nazario, Panto’s servant, a neophyte whose quiet demeanor masked a boiling resentment.

Nazario embodied the paradox of our mission. The Padres saw the Indians as sons, capable of virtue yet prone to sin. Panto, testifying in civil proceedings, admitted to giving Nazario twenty-five lashes days earlier—a “light” punishment, he claimed, unworthy of such vengeance. But Nazario’s account painted a darker truth: frequent, severe floggings drove him to gather “herb powder” and lace the soup, hoping “by poisoning the friar, he would stop punishing [me] so severely.” Here was no martyrdom but a quiet cry against the mission’s yoke.

Soldiers saw Nazario as a criminal, a threat to order. The authorities, swift in their justice, likely returned him to servitude or worse, their leather-clad hands unyielding. To Nazario and his kin, the mission was a cage, its labor and lash a betrayal of the Padres’ promises. Panto’s soup was their rebellion—a small, desperate act against a life of subservience.

Catholic principles of justice and mercy clashed here. Serra’s conviction always held that discipline was a path to salvation, rooted in the Pauline call to “chastise the body” (1 Corinthians 9:27). Yet mercy, too, was their creed—Nazario’s plea for relief might have moved Serra to forgiveness, as he had urged Rivera to seek. It is easy to imagine Panto, chastened by his brush with death, would, on the Doctrina’s call to “love… as Christians,” a lesson lost in the mission’s harsh reality.

The Costanoan Riot: 1812

Another echo of rebellion came in 1812 at Mission Santa Cruz, a riot among unmarried Costanoan neophyte males against Father Ramón Olbés. The informant’s father, a conspirator in Padre Andrés Quintana’s assassination that same year, suggested a deeper unrest. The Costanoan youths, chafing under Olbés’s rule, rose in a tumult—fists raised, voices raw, a storm against the mission’s rigid order.

To the missionaries, the neophytes were the fruit of their labor, baptized into the fold yet restless. Olbés, like Serra, likely saw their rebellion as a test of faith, a call to tighten the reins. To missionaries like Olbrés, the natives were unfulfilled potential, their souls teetering between grace and sin, needing guidance, as the Doctrina urged: “Think about God always.” But the Costanoans saw it differently—labor, filth, cramped quarters, as Borica had noted in his visit and assessment in 1796. Their riot was a bid to reclaim dignity, to shatter the hierarchy that deemed them less than the “gente de razón.”

Ever-vigilant soldiers crushed such uprisings with force, their leather vests stained with the sweat of control. Even Rivera’s legacy, even after his murder in the Quechan (Apache) revolt of 1781 in Arizona, lived on—floggings and imprisonment were the answer to defiance. Like their predecessors, the Costanoans fought for a past the mission sought to erase, their violence a language of survival.

Catholic principles of patience and perseverance framed the missionary response to violence. Serra’s death in 1784, which Palóu greatly mourned, gives us insight into the torch Serra would hope to carry on: “I offer them," Palóu noted, "for His holy service.” Rebellions tested their resolve and were a reminder of the Beatitudes’ call to endure persecution. Yet the mission’s failure to uplift, as Borica observed, gnawed at our ideals—too much a slave, too little a man, the Indian remained.

The soldiers won battles, the Padres their converts, but the Indians paid the price. Catholic principles—love, justice, mercy—guided the missionaries, yet they bent under human frailty in the mission’s shadow. As Palóu wrote in the conclusion of his writing, “the lofty judgments of God are inscrutable.” The rebellions of Alta California, from San Diego’s flames to Santa Cruz’s riot, were not the end but a beginning—a story of faith tested, of lives entwined, of a land forever changed.

For the Indians, life was a crucible. The Kumeyaay, Quiroste, Costanoan, and countless others bent under labor’s weight, their bodies scarred by whips, their spirits by loss. Jayme’s death, Nazario’s poison, the Costanoan riot—these were not mere acts of savagery but cries against a world remade. The neophytes of the missions became fugitives in their land even after secularization’s dawn in 1834.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bolton, Herbert Eugene, ed. Historical Memoirs of New California, by Fray Francisco Palóu, O.F.M. Translated by Herbert Eugene Bolton. 4 vols. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1926.

Engelhardt, Zephyrin. The Missions and Missionaries of California: New Series, Local History. San Francisco: The J.H. Barry Co., 1920.

James, George Wharton. In and out of the Old Missions of California: An Historical and Pictorial Account of the Franciscan Missions. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1905.

Francisco Palou’s Life and Apostolic Labors of the Venerable Father Junípero Serra: Founder of the Franciscan Missions of California. Translated by C. Scott Williams. Pasadena, CA: George Wharton James, 1913.

Jayme, Luis. “Letter of Luis Jayme, OFM, San Diego, October 17, 1772.” Edited by Maynard Geiger. Published for The San Diego Public Library by Dawson’s Book Shop, Los Angeles, 1970.

Palou, Francisco. “List of the Missions.” Unpublished manuscript, 2025. In possession of the author.

Sandos, James A. Converting California: Indians and Franciscans in the Missions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

Starr, Kevin. Continental Ambitions: Roman Catholics in North America: The Colonial Experience. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2016.

Tyler, Helen. “The Family Pico.” The Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly 35, no. 3 (September 1953): 222–23

U.S. National Park Service. The Other Californians.