The Grand Vision

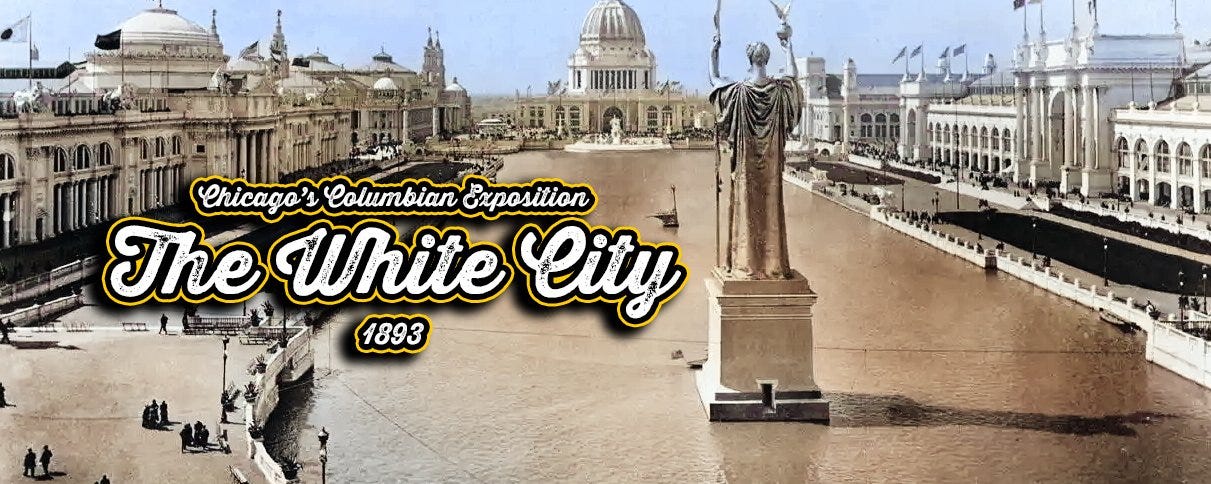

On May 1, 1893, under a cloudless sky on the shores of Lake Michigan, President Grover Cleveland pressed a gold telegraph key. At that moment, the telegraph key was pressed to activate the fair’s electric lights, and the future began. The World’s Columbian Exposition—a triumph of vision, ambition, and sheer determination—illuminated the world. A city had risen where there had been none before, and a White City shimmered with electric lights, symbolizing a nation on the cusp of unimaginable progress. The birth of the White City was a testament to the persistence of Chicago after it was devastated more than a decade prior by the Great Chicago Fire.

It was a fair that nearly didn’t happen. Chicago had fought bitterly to host it, facing down New York, St. Louis, and Washington, D.C., in a battle raging in Congress halls. But on the eighth ballot, the young and hungry Midwestern city secured victory with 157 votes to New York’s 107, leaving its eastern rival stunned. And so, what had once been a swampy stretch of land along the lakefront would be transformed into the most spectacular world’s fair ever conceived.

The idea for the exposition had been circulating for years, with various cities vying to host such a grand celebration of American progress. But Chicago’s civic leaders—led by men like Daniel Burnham, Carter Harrison, and Marshall Field—would not be denied. They marshaled financial resources, secured congressional support, and promised an event to outshine Paris’s Exposition Universelle of 1889.

Once the city secured the bid, the challenge of turning an undeveloped park into a thriving metropolis of progress became a monumental test of American ingenuity. Burnham and his architects, including Charles McKim, Louis Sullivan, and Richard Morris Hunt, set out to create a city of classical beauty and modern efficiency. Frederick Law Olmsted’s landscape vision ensured the fairgrounds were functional and breathtakingly picturesque.

The scale of the exposition’s ambition was staggering. Covering over 600 acres, the fair included 14 main exhibition halls, countless pavilions, and a vast system of canals and lagoons designed to mimic the grandeur of Venice. It was, quite literally, a city within a city—and one built to astonish the world.

The process of constructing the fair was nothing short of miraculous. Chicago’s brutal winters, springtime floods, and the logistical nightmare of coordinating thousands of workers on an impossibly tight schedule meant delays were inevitable. The fair's planners faced crippling labor strikes, material shortages, and political infighting. Yet, Burnham pushed forward with an almost fanatical devotion, rallying his architects and builders with the simple, yet profound motto: “Make no little plans.”

Financing such an undertaking was equally daunting. The fair’s projected cost was an astronomical $28 million, equivalent to nearly three-quarters of a billion dollars today. Most of the funding came from private investors, municipal bonds, and donations from Chicago’s wealthiest citizens, including Marshall Field, Philip Armour, and George Pullman. These industrialists saw the fair as more than just a spectacle; it was a declaration that Chicago—and America—had arrived on the world stage.

Political opposition was fierce, particularly from New York’s financial elite, who resented losing the bid. Eastern newspapers scoffed at Chicago’s ability to host such a grand event, deriding it as a “stockyard city” unworthy of international prestige. But Chicago’s leaders responded with unwavering confidence, determined to prove their city’s mettle.

To make the fairgrounds a reality, thousands of laborers toiled day and night, driving in millions of feet of wooden pilings to stabilize the swampy soil of Jackson Park. Steel, glass, and plaster were transported in vast quantities, and within two years, a city of marble and light rose from the once-empty expanse. Workers sculpted the canals, planted thousands of trees and flowers, and erected the massive domed exhibition halls, their façades gleaming under layers of white paint that gave the White City its name.

At the heart of it all was Burnham’s architectural masterpiece: the Court of Honor, a plaza surrounded by colonnaded palaces reflecting off the waters of the Grand Basin. These buildings, designed in the Beaux-Arts style, evoked the grandeur of ancient Rome and Renaissance Europe and symbolized America’s embrace of classical ideals. At night, the fair glowed with electric light, an awe-inspiring spectacle few had ever witnessed.

Chicago’s citizens, once skeptical, now rallied behind their city’s achievement. Merchants and hoteliers prepared for the influx of millions of visitors, eager to capitalize on the economic boom. Trainloads of people from every corner of the country arrived daily, greeted by banners, brass bands, and the excitement of a city reborn. The fair was not just an exposition—it was the culmination of America’s boundless ambition, a vision of the future unfolding before the world’s eyes.

"Make no little plans; They have no magic to stir men's blood and probably will not themselves be realized. Make big plans, aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone will be a living thing, asserting itself with ever growing insistency. Remember that our sons and grandsons are going to do things that would stagger us." — Daniel Burnham

A City of Light

The White City, as it became known, was an architectural marvel—a utopia built from steel and plaster, designed to astonish and inspire. It was the grand vision of Daniel H. Burnham, who oversaw the Herculean effort of designing and constructing the 600-acre fairgrounds in just 22 months. He was joined by Frederick Law Olmsted, the landscape architect behind Central Park, who transformed the grounds into a harmonious blend of water and greenery, evoking a modern Venice.

Building the fair was an endeavor of unprecedented scale. The timeline was extraordinarily tight, and the challenges were immense. Chicago’s harsh winters, muddy terrain, and high winds threatened construction at every stage. More than 40,000 laborers worked day and night, often in brutal conditions, to meet the deadlines. Materials had to be shipped in from across the country—iron and glass from Pittsburgh, marble from Vermont, and timber from the forests of the Pacific Northwest. The logistics of managing this vast construction effort were overwhelming, requiring constant adjustments, problem-solving, and unrelenting determination.

One of the most incredible feats of engineering was the Manufacturers and Liberal Arts Building, the largest enclosed space ever built at the time. Spanning more than 30 acres, its steel frame was an architectural marvel, setting the stage for the rise of modern skyscrapers in the following decades. The electric lighting system was unlike anything most Americans had ever seen. Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla competed to power the fair. In a dramatic victory, Tesla’s alternating current (AC) technology was chosen over Edison’s direct current (DC), proving its efficiency and safety on an international scale.

Burnham and Olmsted focused on landscaping and aesthetics as the buildings neared completion. They designed cascading fountains, grand promenades, and tranquil lagoons, ensuring the exposition was functional and breathtakingly beautiful. At night, the fair transformed into a dreamlike vision, its brilliant white facades illuminated by thousands of electric bulbs, creating a spectacle never seen in America. The reflection of these glowing structures on the Grand Basin’s waters left visitors in awe.

The public reaction was one of pure astonishment. Visitors arrived by the thousands daily, traveling across the country by train, steamboat, and horse-drawn carriage. They walked through the grand Court of Honor, surrounded by neoclassical buildings that made them feel as though they had stepped into a city of the future. The sheer scale and beauty of the exposition left many speechless, and newspapers across the nation hailed the fair as America’s greatest achievement of the century.

What set the White City apart was its ability to showcase what was possible—not just in architecture and engineering but in the very idea of progress itself. It was more than just a fair; it was a declaration that America was ready to lead the world into the 20th century.

The Age of Innovation

The Exposition was not merely a display of beauty but a showcase of innovation. New products that would define the American consumer experience made their debut. Cracker Jack, Cream of Wheat, Juicy Fruit, Wrigley’s Spearmint Gum, and Pabst Blue Ribbon Beer were all introduced here. We can’t forget that the first ready-mixed pancake flour, known as Aunt Jemima, was also introduced at the World’s Columbian Exposition. In the Machinery Hall, a caramel maker from Pennsylvania named Milton Hershey saw something that changed his life: a German chocolate-making machine. On the spot, he purchased one, and within a decade, he would introduce the Hershey Bar to the world.

The fair was a technological wonderland featuring electric railways, moving sidewalks, and Thomas Edison's showcase of the world’s first-ever voice recording device. The Agricultural Building displayed new machinery that promised to revolutionize farming, while the Transportation Building, designed by Louis Sullivan, featured exhibits on the future of automobiles and railways. Henry Ford, still an unknown mechanic, visited the fair and saw firsthand the innovations that would later inspire him to perfect the automobile assembly line. There were also simpler inventions like the zipper that made its debut.

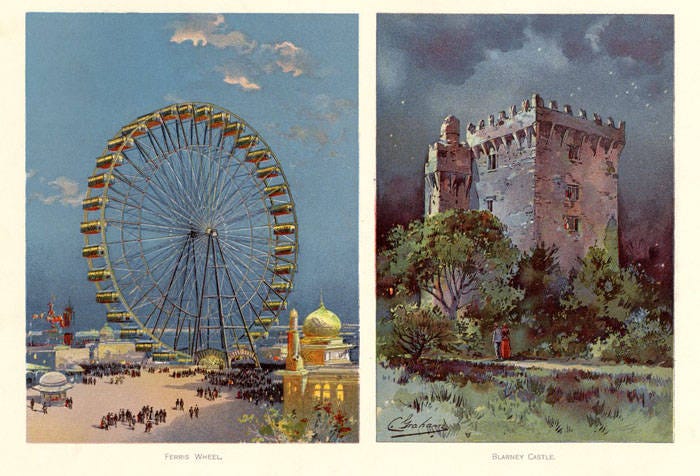

One of the greatest marvels was the Ferris Wheel, America’s bold response to the Eiffel Tower. The structure was designed by George Washington Gale Ferris Jr. and stood 264 feet tall, dwarfing all other attractions. Each of its 36 cars could hold up to 60 passengers, offering visitors a breathtaking panoramic view of the entire fairgrounds and Lake Michigan. It was an instant sensation, proving that American ingenuity could rival—and even surpass—Europe’s engineering feats.

Beyond physical exhibits, the World’s Congress Auxiliary hosted lectures and presentations from some of the greatest minds of the time. Scientific breakthroughs in medicine, physics, and electrical engineering were discussed, shaping the direction of global innovation. Alexander Graham Bell demonstrated his latest advancements in telephony, while Nikola Tesla, fresh off his victory over Edison, exhibited the immense potential of alternating current (AC) power.

The fair had a profound economic impact. Companies that showcased their products saw skyrocketing demand, with millions of visitors eager to bring home newly discovered goods. The burgeoning advertising industry took notes on branding and packaging, learning how to market products to a mass audience. Business magnates like John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie attended the exposition, looking for new ventures to invest in.

The most lasting impact of the fair was its vision of the future. Visitors saw a world where electricity-powered homes, transportation was faster and more efficient, and food and household goods could be mass-produced for an expanding middle class. The Exposition was not just a celebration of what had been achieved—it was a blueprint for the century ahead.

The Cultural Awakening

The World’s Columbian Exposition changed not just technology but also culture. Historian Hubert Howe Bancroft wrote that the White City was a "monument marking the progress of civilization." Words like “ballyhoo” and “cafeteria” entered the American vocabulary. However, perhaps its most enduring cultural legacy came from Katherine Lee Bates, who traveled across the country to visit the fair. Inspired by the grandeur of America’s landscapes, she penned a poem that would become America the Beautiful, forever entwining the fair with the nation’s sense of identity.

Beyond the fair’s grandeur and technological marvels, the Midway Plaisance provided visitors with a spectacle unlike anything they had ever seen. Unlike the refined White City, the Midway was a riot of color, sound, and sensation. Here, cultures worldwide were on display, from Turkish dancers to Japanese teahouses and German beer gardens. It was an explosion of the exotic and the unfamiliar, shaping how Americans saw the world beyond their borders.

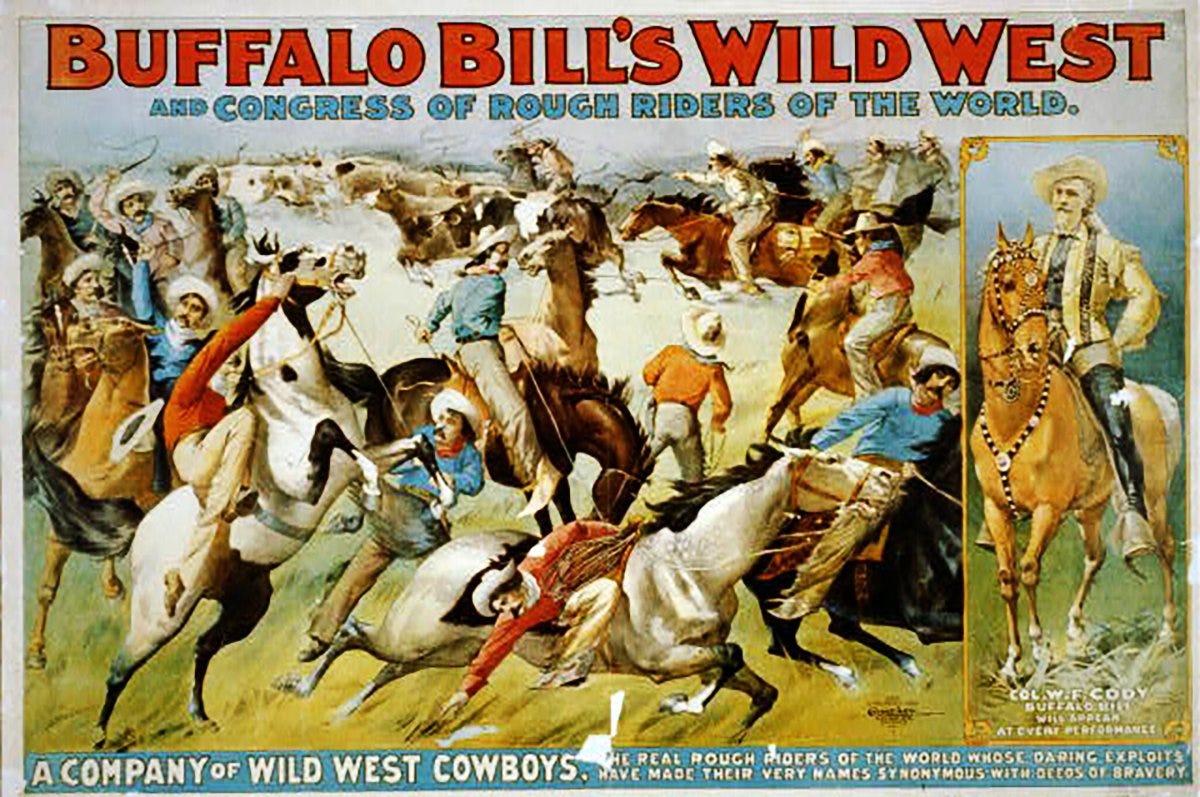

One of the most popular attractions was Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, which, despite being officially excluded from the fair, set up just outside its gates and became an unmissable sensation. William “Buffalo Bill” Cody assembled a cast of cowboys, Native American performers, and trick riders, with Annie Oakley dazzling crowds with her sharpshooting abilities. While it played into romanticized images of the American frontier, it also cemented the myth of the Wild West in American culture.

The fair’s influence on literature and entertainment was profound. L. Frank Baum, later famous for The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, was among its visitors, and many believe that the White City directly inspired his depiction of the Emerald City. Walt Disney was born in Chicago in 1895 at 2156 N. Tripp Avenue. Walt Disney’s father, Elias Disney, worked as a carpenter at the fair. Walt later cited the Exposition as an inspiration for Disneyland, with its carefully designed environments meant to transport visitors into a world of wonder.

The End of the Fair and the Future of America

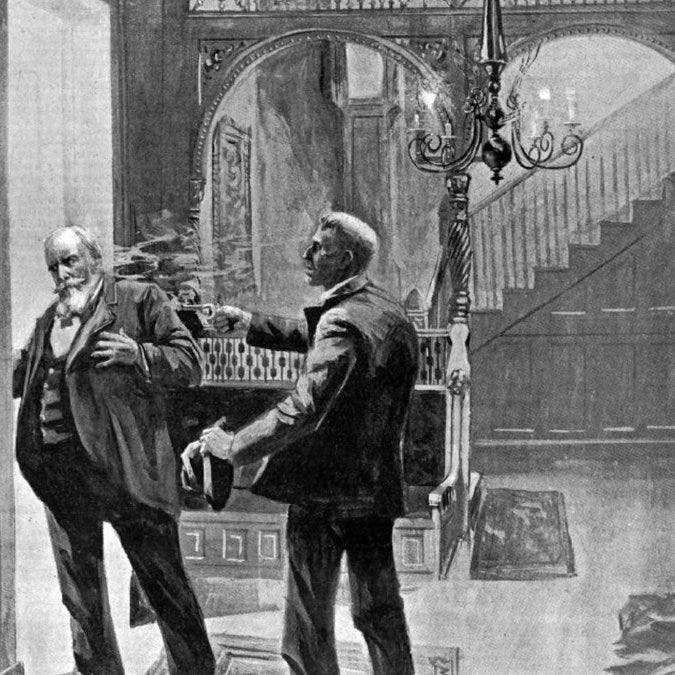

For six months, the fair dazzled 27 million visitors—nearly half of America’s population at the time. On October 9, 1893, Chicago Day, a staggering 750,000 people flooded the fairgrounds, setting a world record. But then, tragedy struck. Just as Chicago prepared to celebrate its greatest triumph, Mayor Carter Harrison Sr. was assassinated. The planned closing ceremonies were canceled and replaced by a somber tribute.

The days after the fair’s closing were marked by reflection and uncertainty. While the Exposition celebrated progress and innovation, it also left behind financial burdens. The fair cost an estimated $28 million, and while ticket sales and sponsorships helped, construction, labor, and maintenance costs left the city with substantial debts. Investors who had poured money into hotels, railroads, and entertainment venues had hoped for continued tourism, but with the fair’s closure, many saw their dreams—and their finances—collapse.

The dismantling of the fairgrounds was a melancholy sight. The Grand White City, built mainly from wood and plaster, was never meant to last. Much of it was torn down within months, and what remained was left to decay. In July 1894, a massive fire swept through the remaining buildings, reducing them to ashes. Only a handful of structures survived, most notably the Palace of Fine Arts, which was later transformed into the Museum of Science and Industry.

Yet, despite the physical destruction, the legacy of the Exposition endured. The City Beautiful Movement, inspired by the fair’s grandeur, led to a new wave of urban planning across America. Burnham’s vision of aesthetic harmony and monumental city design influenced the development of cities like Washington, D.C., San Francisco, and Chicago. The concept of grand boulevards, public parks, and cohesive urban spaces became a standard for American city planning.

Beyond architecture, the fair shaped the nation’s optimism about the future. It cemented America’s place on the global stage, proving that it could host an event that rivaled and even surpassed the great expositions of Europe. The fair introduced millions to electricity, modern machinery, and mass entertainment, leaving them with limitless possibilities.

Figures who had walked its grounds—Henry Ford, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Walt Disney’s father—would take its lessons into the 20th century, shaping how Americans lived, worked, and dreamed. The ideas born at the Exposition fueled industrial expansion, urban growth, and the development of American popular culture.

And so, as the last light of the fair flickered out over the Grand Basin, America stood forever changed—bold, unstoppable, and full of promise for the century ahead. Yet, despite this moment of darkness, the fair had already done its work. It had proven that America could lead the world. And as the last light of the fair flickered out over the Grand Basin, America stood forever changed, its course set toward the future—bold, unstoppable, and full of promise.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. The Book of the Fair: An Historical and Descriptive Presentation of the World’s Columbian Exposition at Chicago in 1893. Chicago: The Bancroft Company, 1893.

National Park Service. "Inventions from the World's Columbian Exposition." Last modified approximately 1.5 years ago. Accessed February 27, 2025.

Percoco, James A. “An Examination of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition.” Organization of American Historians, vol. 5, no. 4 (Spring 1991).

Smith, Andrew F. “Chocolate Confections.” In Daily Life through History, ABC-CLIO, 2018.