Andrew Carnegie Steel

Andrew Carnegie’s ascent from a telegraph clerk at the age of seventeen to one of the wealthiest men in American history is a story of ambition, innovation, and the transformative power of industrial capitalism. Carnegie began his career as a secretary to the head of the Pennsylvania Railroad and soon moved on to Wall Street, where he brokered railroad bonds for massive commissions, quickly becoming a millionaire.

In 1872, Carnegie visited London and witnessed the groundbreaking Bessemer process, a new method for producing steel that drastically reduced costs. Inspired, he returned to the United States and built a million-dollar steel plant near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Strategically located with access to two railroad lines and the Monongahela River, Carnegie’s plant utilized the most up-to-date Bessemer technology, cutting the cost of making steel rails by more than half. Many writers later claimed that Carnegie said, “Take away my people, but leave my factories, and soon grass will grow on the factory floors. Take away my factories, but leave my people, and soon we will have new and better factories.” Though this ethos certainly defined Carnegie’s approach to business, it serves as the historical myth and legend of Carnegie as much as it does his ethos.

Carnegie pioneered the system of vertical integration, guaranteeing the lowest costs and maximum output by controlling all aspects of production—from mining raw materials to transporting finished goods. This system allowed Carnegie Steel to dominate the market, producing 10,000 tons of steel per month by 1880 and generating profits of $1.5 million annually. By 1900, Carnegie Steel’s profits had soared to $40 million, making Carnegie a central figure in the American steel industry.

Despite his industrial success, Carnegie’s methods were often ruthless. He pitted managers against one another to drive performance and subjected workers to long hours, low wages, and dangerous conditions. In addition, Carnegie leveraged his influence in Congress to secure protective tariffs, keeping foreign competitors at bay.

Carnegie’s dominance of the steel industry reached its zenith in 1900 during a fateful dinner with J.P. Morgan. It has been claimed that Morgan asked Carnegie to name the price for his steel business, and Carnegie famously (whether fact or fiction) scribbled $492 million on a slip of paper. Morgan agreed and consolidated Carnegie Steel with other holdings to form U.S. Steel, the world’s first billion-dollar corporation. Reflecting on his achievement, Carnegie’s writings reveal his belief in the moral responsibility of wealth: “The man who dies rich, dies disgraced.” True to this ideal, Carnegie gave away over $300 million in his lifetime, funding public libraries, educational institutions, and cultural initiatives that burnished his public image as a philanthropist.

“In 1901, financier J.P. Morgan orchestrated the creation of United States Steel by consolidating eight leading steel companies, including Carnegie Steel. This monumental merger resulted in the world's first billion-dollar corporation, with U.S. Steel capitalized at $1.4 billion.” — American Yawp

J.P. Morgan and Finance Capitalism

J.P. Morgan, the scion of a banking family, wielded extraordinary influence over American finance and industry. During the Civil War, Morgan purchased defective rifles for $3.50 each and resold them to a Union general for $22 apiece, a deal upheld by a federal judge despite its unethical implications. Morgan’s power grew as his firm, Drexel, Morgan and Company, secured lucrative government contracts, including a $260 million bond float that netted the firm $5 million in commissions.

Critics of Morgan’s financial empire decried his control of a vast “money trust,” which dominated American banking. Morgan himself loathed competition, preferring consolidation and central control. He became a key architect of business mergers, creating General Electric and U.S. Steel and reorganizing the nation’s railroads. While his interventions brought stability to struggling industries, they also saddled companies with enormous debts and prioritized short-term profits over long-term innovation.

Morgan’s rivalry with Carnegie culminated in the steel industry. By 1898, Morgan supervised mergers of smaller companies to challenge Carnegie Steel’s dominance. When Carnegie sold his company to Morgan in 1900, it marked the transition from the entrepreneurial age of industrialists like Carnegie to the corporate era epitomized by Morgan. U.S. Steel became the largest corporation in the world, symbolizing the new industrial order. Together, Carnegie and Morgan shaped American capitalism's trajectory, embodying its innovative potential and ethical complexities.

Cornelius Vanderbilt: Controversial Tycoon

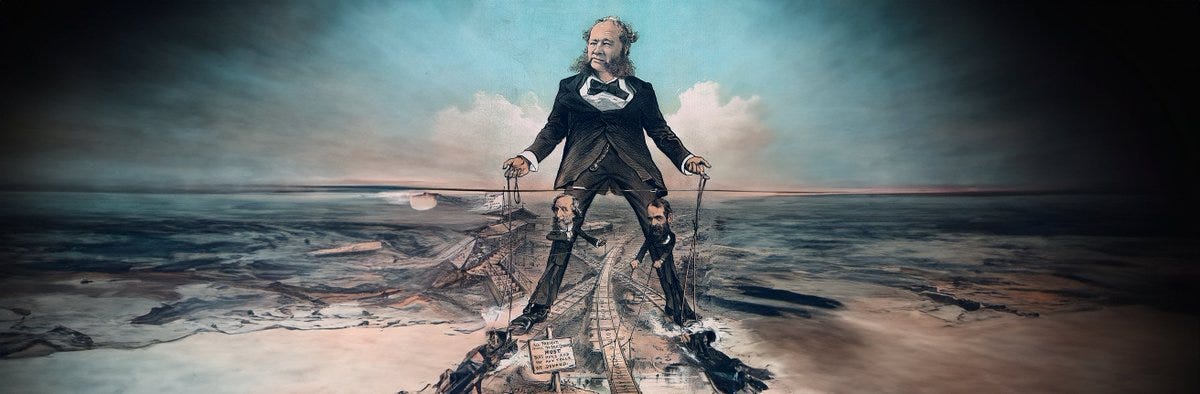

Cornelius Vanderbilt became synonymous with American industrial growth. His influence stretched across the waterways and railroads, fueling the nation’s economic rise. Vanderbilt’s contributions to developing the United States’ transportation networks were transformative, creating more efficient systems for moving goods and people during a time of rapid industrialization. However, his path to power was marked by relentless competition and ruthless tactics, earning him both admiration and condemnation.

Vanderbilt’s first economic triumph came in the steamboat industry. In the early 19th century, he revolutionized waterborne commerce by introducing faster and cheaper transportation services, often slashing fares to drive competitors out of business. His mastery of efficiency allowed him to dominate the steamboat trade in and around New York, cementing his reputation as a savvy and strategic businessman. By the 1840s, Vanderbilt had amassed a significant fortune, which he later used to pivot into the burgeoning railroad industry.

It was in railroads that Vanderbilt’s influence reached its zenith. During the 1860s and 1870s, he acquired and consolidated several key lines, including the New York and Harlem Railroad, the Hudson River Railroad, and the New York Central. Vanderbilt’s foresight in streamlining these operations connected major urban centers and created a vital economic artery linking the East Coast to the Midwest. His improvements in scheduling, track standardization, and management practices became a blueprint for modern corporate efficiency, driving down costs and fostering commerce across the nation.

Yet Vanderbilt’s rise in the railroad industry was not without contention. His rivals, such as Daniel Drew and Jay Gould, often bore the brunt of his aggressive tactics. Vanderbilt orchestrated daring stock manipulations and leveraged his considerable resources to outwit competitors in battles that shaped Wall Street’s early history. His 1864 takeover of the Hudson River Railroad involved a contentious stock-buying campaign, leaving shareholders and competitors scrambling.

Critics accused Vanderbilt of caring little for the public good, a claim bolstered by his infamous retort to calls for charity: “Let them do what I have done.” This statement encapsulated his staunch belief in self-determination and the free market, but it also highlighted the era’s broader struggles with wealth inequality and corporate power. Many viewed Vanderbilt as the quintessential “robber baron,” a man whose actions advanced industry while exploiting workers and crushing competition.

Despite the controversies, Vanderbilt’s contributions to America’s economic infrastructure remain undeniable. His railroads spurred the growth of new markets and industries, creating opportunities for countless entrepreneurs and workers. By modernizing transportation, Vanderbilt played a pivotal role in shaping the American economy during its transition to an industrial powerhouse. His legacy endures as a reminder of the Gilded Age’s dynamism and its moral complexities—an era where progress and exploitation walked hand in hand.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Corbett, P. Scott, Volker Janssen, John M. Lund, Todd Pfannestiel, Paul Vickery, and Sylvie Waskiewicz. U.S. History. Houston, TX: OpenStax, Rice University, 2014. https://openstax.org/details/books/us-history.

Locke, Joseph, and Ben Wright, eds. The American Yawp. http://www.americanyawp.com/.

Schweikart, Larry, and Michael Allen. A Patriot's History of the United States: From Columbus's Great Discovery to the War on Terror. New York: Sentinel, 2004.

Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. New York: Harper & Row, 1980.

Quote: “Let them do what I have done.” cited from Cassandra Schumacher, Cornelius Vanderbilt: Railroad Tycoon (New York: Cavendish Square, 2019), 79.