Uncovering Charles Cristadoro: A Historian’s Quest for a Forgotten Savant

Hollywood Through the Eyes of Charles Cristadoro, Vol. II

“Art exists to sweeten life; it is the dress of form, the color of expression. Life is the all-important thing…the first great work of art…a truly cultured being.”

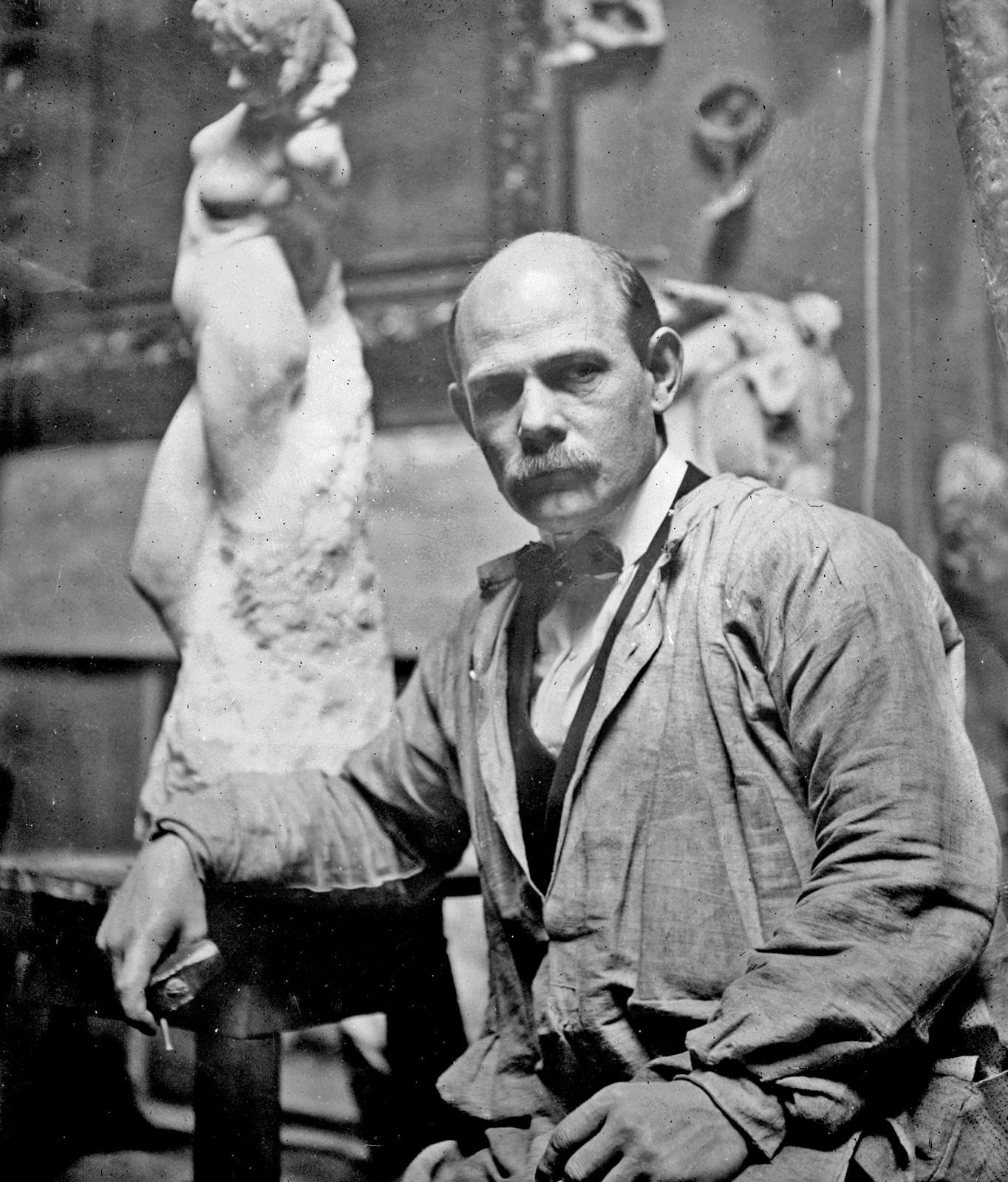

Gutzon Borglum, Mentor of Charles Cristadoro and creator of Mount Rushmore

In the summer of 2011, as a graduate history student interning at the William S. Hart Museum, I embarked on a quest to unearth the story of Charles Cristadoro, an artist whose name had faded into obscurity since his death in 1967. The museum, nestled in the Santa Clarita Valley, had struggled for decades to piece together the fragments of Cristadoro’s life. What began as a modest research project soon unfolded into a journey through the vibrant tapestry of early 20th-century American art and Hollywood’s golden age, revealing a man whose contributions touched the luminaries of his era and shaped cultural milestones, yet remained largely forgotten.

Charles Cristadoro was no mere footnote. To the casual observer, his name might evoke a shrug, a fleeting curiosity dismissed as inconsequential. The archives at the Seaver Center for Western History Research offered only a handful of documents—barely enough to fill a single typed page. Early attempts to contact those who might have known him yielded little; the few who recalled his name offered only vague impressions, and I assumed his contemporaries were either long gone or unreachable.

Yet, driven by an instinct, I ventured to the Los Angeles Public Library in downtown Los Angeles, hoping its vast collections might hold a clue to Cristadoro’s elusive legacy. At the library’s reference desk, a chance encounter changed everything. When I mentioned Cristadoro’s connection to puppets and Disney’s Pinocchio, an older librarian’s eyes lit up. She handed me a business card emblazoned with a clown and bold red lettering: Bob Baker Marionette Theater, 1345 West 1st Street, Los Angeles. “If anyone knows about puppets and Pinocchio, it’s Bob Baker,” she said.

Skeptical but intrigued, I dialed the number and left a message, expecting little. The next day, a voicemail from Baker himself crackled with excitement: “Please call me, I have been waiting for fifty years to tell someone about Cris!” A meeting was set, and suddenly, the trail grew warm.

The Bob Baker Marionette Theater, a small, historic gem in a rapidly gentrifying corner of downtown Los Angeles, welcomed me with the charm of a bygone era. Staff members bustled about, preparing milk and cookies for children attending a matinee performance. A hallway lined with puppets and plaques honoring Baker’s contributions led to his office, a cluttered shrine to Hollywood’s past, filled with photographs, papers, and memorabilia.

There sat Bob Baker, a man whose youthful energy belied his years, juggling a phone call with the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power while eagerly awaiting our interview. His voice, bright and animated, carried the cadence of a showman, and his memories of Cristadoro poured forth with vivid clarity.

“Cristadoro imagined a world in 2000 that would be an amazing place,” Baker began, “but in his own life, his world was more magnificent than most.” What followed was a cascade of revelations. Cristadoro had been a sculptor, puppeteer, ivory carver, and modernist pioneer, leaving his mark on institutions and individuals who defined American culture. He worked with Walt Disney, contributing to the early vision of what would become the Imagineers. He crafted puppets for Pinocchio and collaborated with William S. Hart, the silent film star, who paid him handsomely for over a decade to serve as his personal artist. Cristadoro’s bronze medal at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in 1915 and his celebrated King Neptune float at the Panama-California Exposition showcased his versatility.

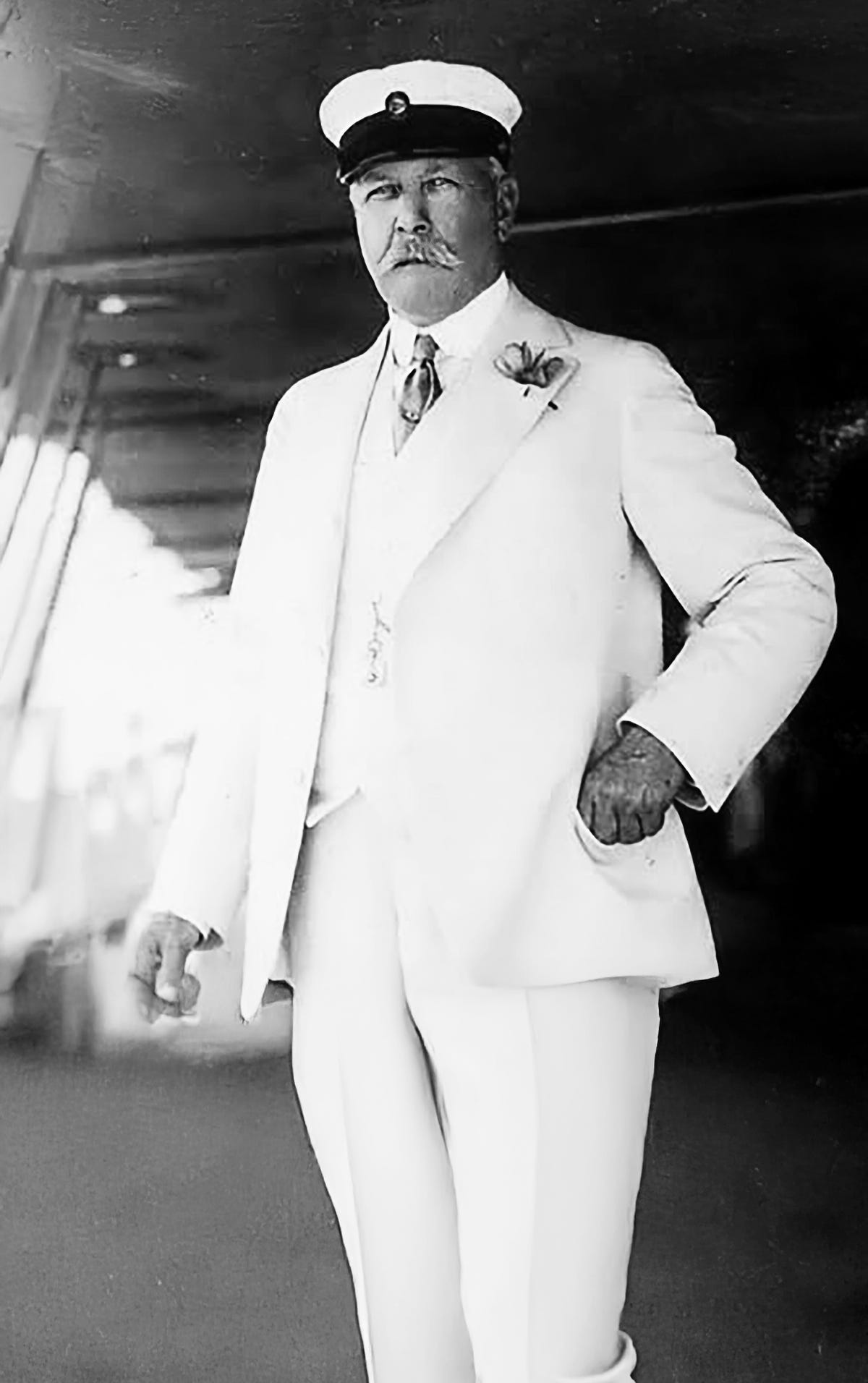

His connections spanned a constellation of stars: Buddy Ebsen, Gutzon Borglum, Robert Henri, Charles Lindbergh, Will Rogers, Charlie Chaplin, Fay Wray, and Frederic Remington. As Baker spoke, Cristadoro emerged not as a transient artist but as a hidden titan of Hollywood and American art.

Cristadoro’s story began far from California’s sunlit shores. Born in New York, his family relocated to Minnesota, where he displayed prodigious talent as a young boy. At twelve, he traveled to Chicago with his art school classmates to participate in the 1893 Columbian Exposition, an experience that ignited his passion for sculpture.

Later, he studied at the Old Chase School, which evolved into the Art Students League of New York, the first truly American art institution aimed at fostering homegrown talent. Under the tutelage of masters like Frederick DuMond, F. Luis Mora, and Robert Henri, Cristadoro refined his skills in drawing, illustration, and painting, joining a generation of artists who would forge a distinctly American aesthetic. Others in the same circle, including Borglum and Remington, became architects of an artistic revolution that radiated from New York to the burgeoning cultural hubs of Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Diego. A tragic accident propelled Cristadoro toward California.

In Minnesota, as his father, Charles, retrieved a pistol from his desk to ensure his son’s safety on a planned trip west, the gun misfired, leaving him paralyzed. The harsh Minnesota winters exacerbated his condition, prompting the family to seek the milder climate of San Diego around 1908. The move proved fortuitous. San Diego’s elite, led by magnate John D. Spreckels, were determined to rival San Francisco as a cultural and economic powerhouse on the Pacific Coast.

Cristadoro arrived at a moment of opportunity, immersing himself in the city’s burgeoning art scene and contributing to its cultural ascent through his work at the Panama-California Exposition and beyond. Through Baker’s recollections and my own archival discoveries, Cristadoro’s life came into focus: a man whose artistic vision and personal connections bridged the worlds of fine art, film, and popular culture.

His contributions to Disney, Hart, and the modernist movements of Southern California revealed a figure who deserved far more than a footnote in history. What began as a routine internship project had become a journey into the heart of an era, uncovering a story that resonated with the ambition, creativity, and resilience of early 20th-century America.

SOURCES | BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baker, Bob. Interview by V. P. Romo. Discussion of Charles Cristadoro, Los Angeles, CA, June 24, 2011.

South, Will, Marian Yoshiki-Kovinick, and Julia Armstrong-Totten. A Seed of Modernism: The Art Students League of Los Angeles, 1906–1953. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2008.