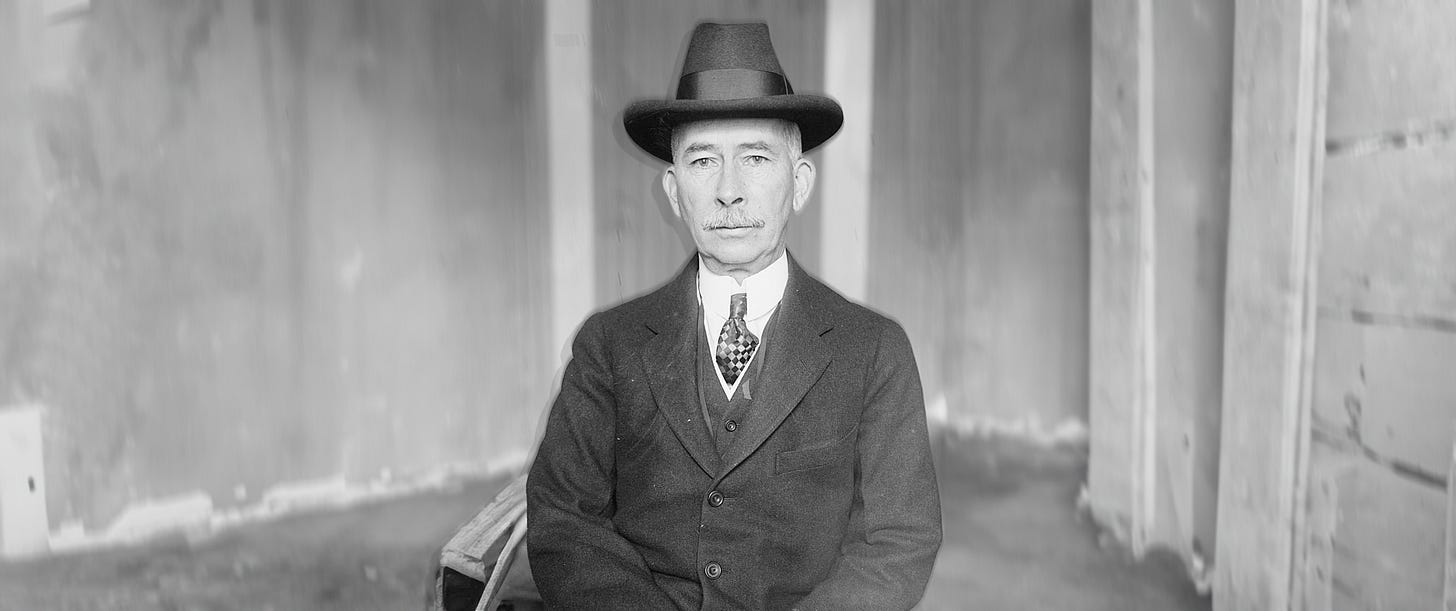

In December of 1918, the boulevards of Paris were crowded with jubilant throngs. Flags waved in the winter air, voices rose in praise, and the great and the hopeful alike craned their necks for a glimpse of the man many believed would lead the world into a new and better age. Woodrow Wilson, President of the United States, rode through the Place de la Concorde as the guest of a grateful Europe. He smiled and bowed from his carriage, every inch the scholar-statesman. At that moment, there was no figure on earth more acclaimed.

Among those who watched Wilson pass that day was W.E.B. Du Bois, scholar, writer, and a man whose faith in Wilson’s leadership had long since been dashed. He had not seen Wilson in person before. There he was, the “foremost figure in the world,” as Du Bois would later recall—yet Wilson seemed oblivious to the enormity of the challenges before him. “He enjoyed the adulation,” Du Bois noted. “He smiled and bowed right and left and seemed to have no apprehension of the difficulty, perhaps the impossibility, of the task that lay before him.”

For Du Bois, this scene carried a bitter irony. Only a few years earlier, he had believed that Wilson might be a president of a different sort, one who could finally reconcile the sins of America’s racial past with the ideals of its founding documents. That hope would end in profound disappointment.

The Promise

Du Bois had watched the election of 1912 with cautious optimism. Disgusted with the Republican Party’s treatment of its Black supporters and disillusioned by Theodore Roosevelt’s political calculations—particularly his alliance with Southern "lily whites"—Du Bois turned his attention to Woodrow Wilson. Wilson was an intellectual, a professor, a man of books and ideas. Years before, they had both contributed essays to a symposium on the Civil War and Reconstruction in The Atlantic Monthly. If anyone might steer the Democratic Party away from its anti-Black orthodoxy, it was Wilson. Or so Du Bois thought.

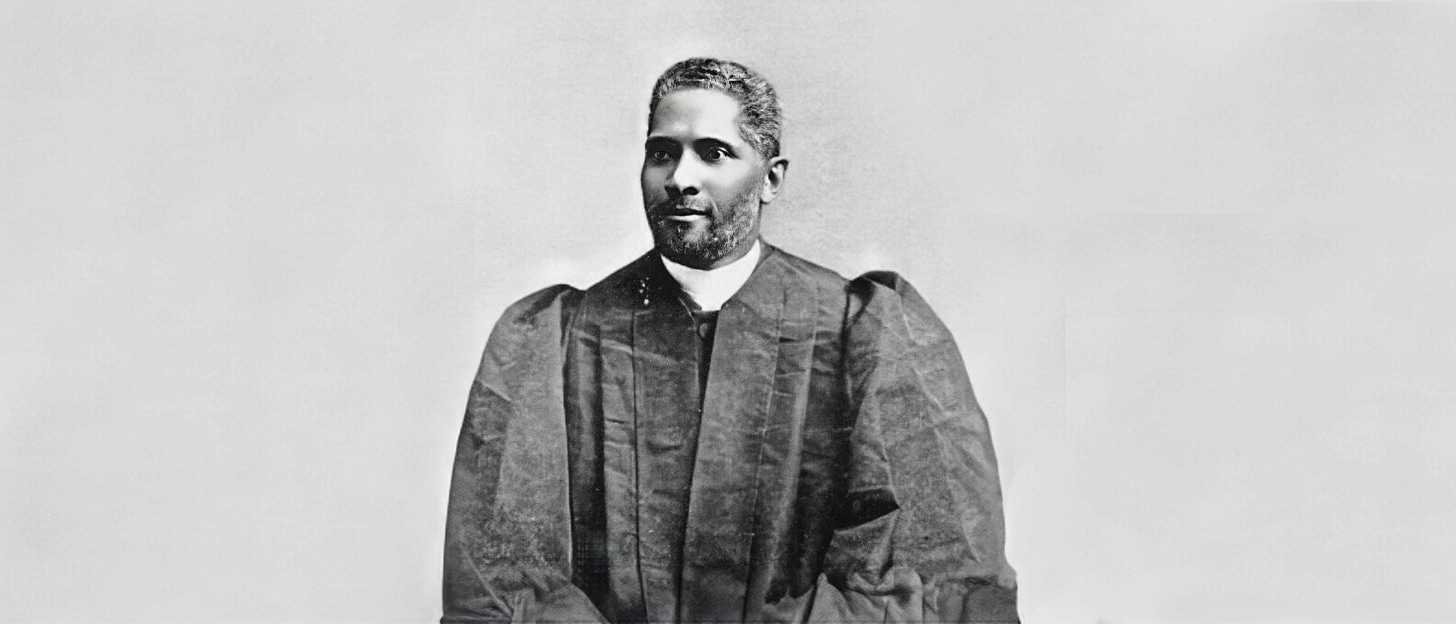

Bishop Alexander Walters, a respected Black clergyman, shared that hope. He visited Wilson during the campaign and returned with a letter that seemed to promise much. In Wilson’s own hand, he expressed his desire to see justice done to Black Americans—“not mere grudging justice, but justice executed with liberality and cordial good feeling.” On the surface, it was a remarkable statement from a candidate of the Democratic Party, the party of the old Confederacy.

Du Bois was convinced. He placed the growing influence of The Crisis magazine behind Wilson’s candidacy. He campaigned, wrote leaflets, and made speeches. Many African Americans who had grown weary of Republican neglect cast their votes for the Democratic ticket for the first time. When Wilson won, Du Bois and others believed they had played a small but significant part in his victory. What followed was a swift and devastating betrayal.

The Betrayal

Once in office, Wilson proved unwilling to keep his promises. Southern Democrats flooded into Washington, seeing the election of one of their own as a signal to impose new, harsh restrictions on Black Americans. In Congress and state legislatures, bills sprang up like weeds after a rain: anti-intermarriage laws, housing segregation, Jim Crow streetcar ordinances—even in the District of Columbia.

Du Bois and his allies sought to hold Wilson to his word. Through intermediaries like Oswald Garrison Villard, they petitioned the president to endorse a national commission on race relations. There was no response. Instead, the new administration sanctioned segregation in the federal civil service. Black clerks, who had once worked alongside white colleagues, were now separated by screens and walls, their movements restricted, their opportunities for promotion sharply curtailed. Photographs were required on job applications, and a thin veil was required for racial exclusion. Du Bois would write in The Crisis, addressing Wilson directly:

“Sir, you have now been President of the United States for six months and what is the result? It is no exaggeration to say that every enemy of the Negro race is greatly encouraged.”

Despite Wilson’s silence, Du Bois and others pressed on. They sent open letters, held protests, and met with administration officials. One such meeting, led by William Monroe Trotter, ended in a confrontation with the president. Trotter, blunt and direct, demanded an end to segregation in federal employment. Wilson bristled. “Your tone, sir, is insulting,” he said. Trotter, unflinching, replied, “I am only emphasizing the sincerity of my convictions.” The meeting failed.

By 1915, Bishop Walters himself met again with Wilson. The president was cordial and offered the bishop a diplomatic post in Liberia, which Walters declined. Then came a final indignity. Wilson, in passing, asked Walters about the letter he had written in 1912—the letter that had pledged “liberality and cordial good feeling” toward Black Americans. Walters, eager to affirm its importance, produced the letter from his pocket. Wilson took it, set it on his desk, and never returned it.

The Wartime President

As the country entered the Great War, there were signs that Wilson had begun to grasp the enormity of the racial problem, if only faintly. With new advisers like Secretary of War Newton Baker, there were modest efforts at fairness. Black officers were trained and commissioned for the first time. A conference of Black editors met in Washington, and Wilson finally condemned lynching—his first such statement as president.

But, discrimination persisted. Black troops returning from Europe were treated with contempt. In The Crisis, Du Bois published a secret document from the U.S. Army advising French commanders to view Black soldiers with suspicion. The post office briefly suppressed the issue. Wilson sent Dr. Robert Moton, the president of Tuskegee Institute, to France to counsel returning Black troops toward restraint and patience at home. This role placed Moton in an impossible position.

Versailles and After

Du Bois sailed for Paris in 1919 aboard the Orizaba, determined to give voice to Africa and the darker races of the world at the Versailles Peace Conference. He was placed under surveillance and forbidden from addressing Black troops in France. Yet, he managed to convene a Pan-African Congress in Paris despite opposition from the American delegation.

There was no audience with Wilson. Instead, Du Bois met with Colonel House, the president’s trusted adviser, who listened politely but made no commitments. Wilson, who had once spoken eloquently of self-determination and justice, now viewed African colonies as commercial opportunities. Du Bois, who had respected Wilson’s scholarship, was left disillusioned. At Versailles, Wilson seemed out of his depth, unable to understand Europe, much less the broader world of race and empire.

Looking back, Du Bois saw Wilson not as a villain but as a tragic figure—an idealist in theory whose practice was subject to prejudice and political expediency. For Black Americans, the Wilson years were a time of broken promises and bitter lessons. The high hopes of 1912 had given way to the harsh reality of segregation, disenfranchisement, and exclusion.

For Du Bois, the memory of that December day in Paris lingered. Riding through the Place de la Concorde, Wilson basked in the crowds' adulation, confident in his mission. But for those who had once believed in him and counted on his sense of justice, he had already failed.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Du Bois, W. E. Burghardt. "Woodrow Wilson." The Journal of Negro History 58, no. 4 (October 1973): 453–459. https://doi.org/10.2307/2716751.

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library. "Bishop Alexander Walters." New York Public Library Digital Collections.