In Europe before 1914, a continent basking in decades of relative peace, its cities were alive with the hum of progress and the glitter of empire. Yet, beneath this serene surface simmered a volatile brew of nationalism and imperialism—forces as old as time, yet newly sharpened by ambition and rivalry.

The European powers, wary of the sparks that might ignite this tinderbox, wove a complex web of alliances, a diplomatic dance meant to preserve the balance of power. On one side stood the Triple Alliance—Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy—a formidable triad bound by mutual defense. Across the divide loomed the Triple Entente, or the Allies—Great Britain, France, and Russia—equally resolute, equally armed. These pacts, intended as a bulwark against war, instead stretched the threads of tension taut, magnifying the risk that a single misstep might unravel the peace.

That misstep came on a sunlit day in Sarajevo, June 28, 1914, when a Bosnian Serb nationalist, driven by dreams of independence, fired the shots that felled Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne. The echoes of those bullets reverberated far beyond the Balkan hills.

Within weeks, the intricate machinery of alliances whirred into motion, transforming a local quarrel into a conflagration that engulfed Europe. Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, Russia mobilized in Serbia’s defense, and Germany, bound by its pact, leapt to Austria’s side. France and Britain, tethered to Russia, soon joined the fray. With breathtaking speed, what began as a regional dispute had become a war of nations.

The conflict swelled beyond Europe’s borders, drawing in distant powers with their own ambitions. Japan, sensing opportunity, entered the fray against Germany in August 1914, eager to oust European rivals from China and claim a stronger economic foothold in the Pacific. Thus, the war stretched its shadow across continents, earning the name by which history would know it: the Great War, the First World War—a struggle that would test the mettle of empires and the resilience of men.

Across the Atlantic, President Woodrow Wilson watched this unfolding calamity with a scholar’s eye and a preacher’s heart. A man of lofty ideals, he declared the war a European affair, distant from America’s vital interests and untethered to any grand principle worth her blood.

On August 4, 1914, as the guns roared overseas, Wilson proclaimed the United States neutral, pledging to maintain normal relations with all belligerents. Yet neutrality proved a fragile creed. Wilson’s own sympathies—and those of many Americans—tilted toward Britain and France. With Britain, they shared a tongue and a heritage; with France, a debt from the days of the Revolution. Germany, by contrast, stood as a monarchical enigma, its militarism a stark counterpoint to democratic ideals.

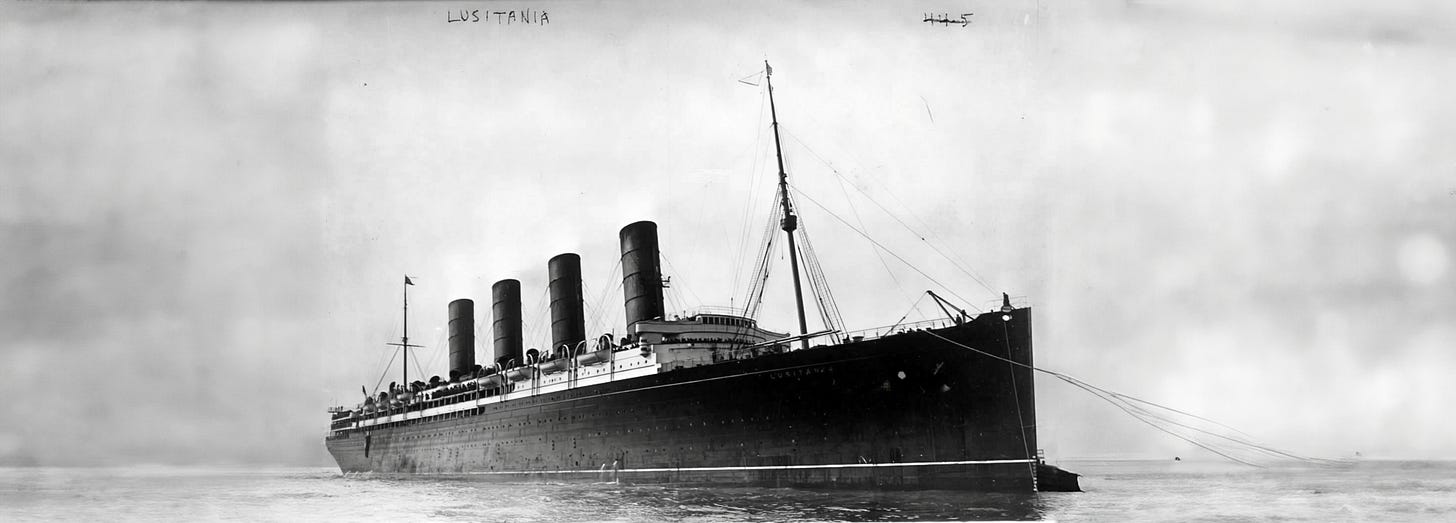

Britain struck the first blow against this neutrality, deploying its formidable navy to choke Germany’s trade with an economic blockade. America protested, but Germany’s response was more dire. In February 1915, Berlin unleashed its submarines—U-boats, as they were called—to blockade British ports, sinking ships with ruthless efficiency. The crisis reached a crescendo on May 7, 1915, when a German U-boat torpedoed the Lusitania, a British passenger liner steaming toward Liverpool.

The ship went down with over 1,000 souls, including 128 Americans. The nation recoiled in horror. Some clamored for war, their voices rising in indignation; others, more cautiously, noted the ship’s cargo of munitions, deeming it a legitimate target. Wilson, ever the mediator, charted a middle course. He condemned the attack but held fast to peace, demanding that Germany cease such assaults on civilian vessels. When Berlin offered an apology and a pause in unrestricted submarine warfare, the storm subsided—for a time.

Wilson’s deft handling of the Lusitania crisis bolstered his standing as he faced reelection in 1916. Campaigning under the banner “He Kept Us Out of War,” he cast himself as the guardian of peace, a steady hand amid global tumult. The voters rewarded him with a narrow victory—600,000 popular votes and a mere 23 electoral votes separated him from his Republican rival, Charles Evans Hughes. It was a testament to the nation’s ambivalence: a desire for peace, yet a growing unease as the war’s ripples lapped at America’s shores.

Wilson sought to redefine America’s role at home in its own hemisphere. Dismissing the muscular interventions of his predecessors—Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft—he envisioned a foreign policy rooted in principle rather than power. To this end, he tapped William Jennings Bryan, a pacifist and three-time presidential hopeful, as secretary of state. Together, they upheld the Monroe Doctrine, that venerable edict asserting U.S. primacy in the Western Hemisphere. Yet their actions belied their rhetoric. In Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic, American troops landed to quell unrest, ostensibly to protect interests and restore order.

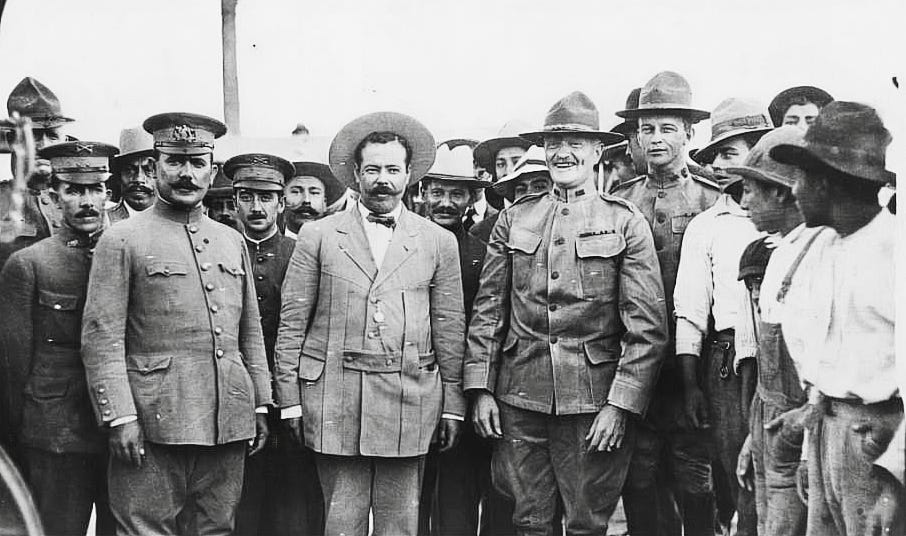

Nowhere was this paradox more evident than in Mexico. In 1910, revolution had erupted south of the border, a tempest of reform and bloodshed. By 1913, General Victoriano Huerta seized power in a brutal coup, earning Wilson’s scorn as a “government of butchers.” In April 1914, Wilson dispatched 800 Marines to Veracruz, ousting Huerta and installing a regime more to his liking.

Yet, the saga did not end there. Francisco “Pancho” Villa, a revolutionary turned bandit, emerged as a thorn in Wilson’s side. After Villa’s forces raided Columbus, New Mexico, in March 1916, killing 18 Americans, Wilson ordered General John J. Pershing to pursue him across the border. For nearly a year, Pershing’s troops—bolstered by Apaches, automobiles, and even primitive airplanes—chased the elusive Villa through Mexico’s deserts, a futile hunt that ended only when war in Europe beckoned Pershing elsewhere.

By 1917, the fiction of American neutrality began to fray. Though irksome, the British blockade was tolerated; the United States supplied Britain with 40% of its war materiel and floated loans to London and Paris. Germany, squeezed by this stranglehold, grew desperate. On January 31, 1917, Berlin announced the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, betting it could starve Britain into submission before America could intervene.

The gamble proved costly. In March, German U-boats sank five American merchant ships off Britain’s coast, claiming 66 American lives. Then came the Zimmerman Telegram, an intercepted missive revealing Germany’s audacious bid to entice Mexico into war against the United States, promising lost territories in return. The revelation shattered Wilson’s hopes for a negotiated peace.

On April 2, 1917, Wilson stood before Congress, his voice steady but resolute. “The world must be made safe for democracy,” he declared, requesting a declaration of war. Four days later, on April 6, Congress obliged, with only a handful dissenting—among them Jeannette Rankin of Montana, the first woman elected to that august body. America, at last, had joined the Great War.

The nation Wilson led into battle was untested, its army a mere skeleton of volunteers. On May 18, 1917, he signed the Selective Service Act, summoning millions of young men to the colors. From farms and factories, they came—a vast, raw force transformed into the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) under General John “Black Jack” Pershing, a stern commander of unblemished repute.

At home, Wilson stoked the fires of patriotism. The Committee on Public Information, led by muckraker George Creel, unleashed a torrent of propaganda—films vilifying the Kaiser, “Four-Minute Men” delivering rousing speeches, and a campaign that turned sauerkraut into “liberty cabbage.” Yet this fervor had its dark side. The Espionage Act, Trading with the Enemy Act, and Sedition Act armed the government with sweeping powers to silence dissent, a stark irony for a war fought in democracy’s name.

When the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) reached France, they found a war mired in mud and blood. For three years, the Allies and Germans had clawed at each other across a scarred landscape of trenches, their advances measured in yards, their losses in legions. Into this stalemate stepped the Americans, brash and unseasoned, their rifles—Springfields and borrowed Enfields—shouldered alongside machine guns and artillery borrowed from their weary allies.

In May 1918, at Belleau Wood, they clashed with the Germans in a brutal ballet of bayonets and bullets, proving their valor and turning the tide. By summer, the Allies launched a counteroffensive, driving the Germans back along the Marne. On November 11, 1918, an armistice silenced the guns, ending a war that claimed 112,000 American lives—a toll surpassed only by the Civil War—and left Europe a graveyard of empires.

Even as the cannons cooled, Wilson dreamed of a new world. On January 8, 1918, he unveiled his Fourteen Points, a blueprint for peace rooted in self-determination, free trade, and a League of Nations to guard against future strife. He fought for this vision at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, but the Allies—hardened by loss—demanded retribution.

The Treaty of Versailles, signed in June, bore Wilson’s imprint and his compromises: Germany was saddled with guilt and reparations, and its colonies were parceled under League mandates. Back home, the Senate balked, led by Henry Cabot Lodge, who feared the League would bind America’s hands. Wilson, undeterred, took his case to the people, only to collapse from a stroke in October 1919. The treaty faltered, with it, America’s place in the League. The world Wilson sought to remake slipped from his grasp, a noble ambition undone by the frailties of men and nations.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

"U.S. History." OpenStax, 2016.

The American Yawp. Stanford University Press, 2022.

Schweikart, Larry, and Michael Allen. A Patriot's History of the United States: From Columbus's Great Discovery to the War on Terror. New York: Sentinel, 2004.

Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. New York: Harper & Row, 1980.