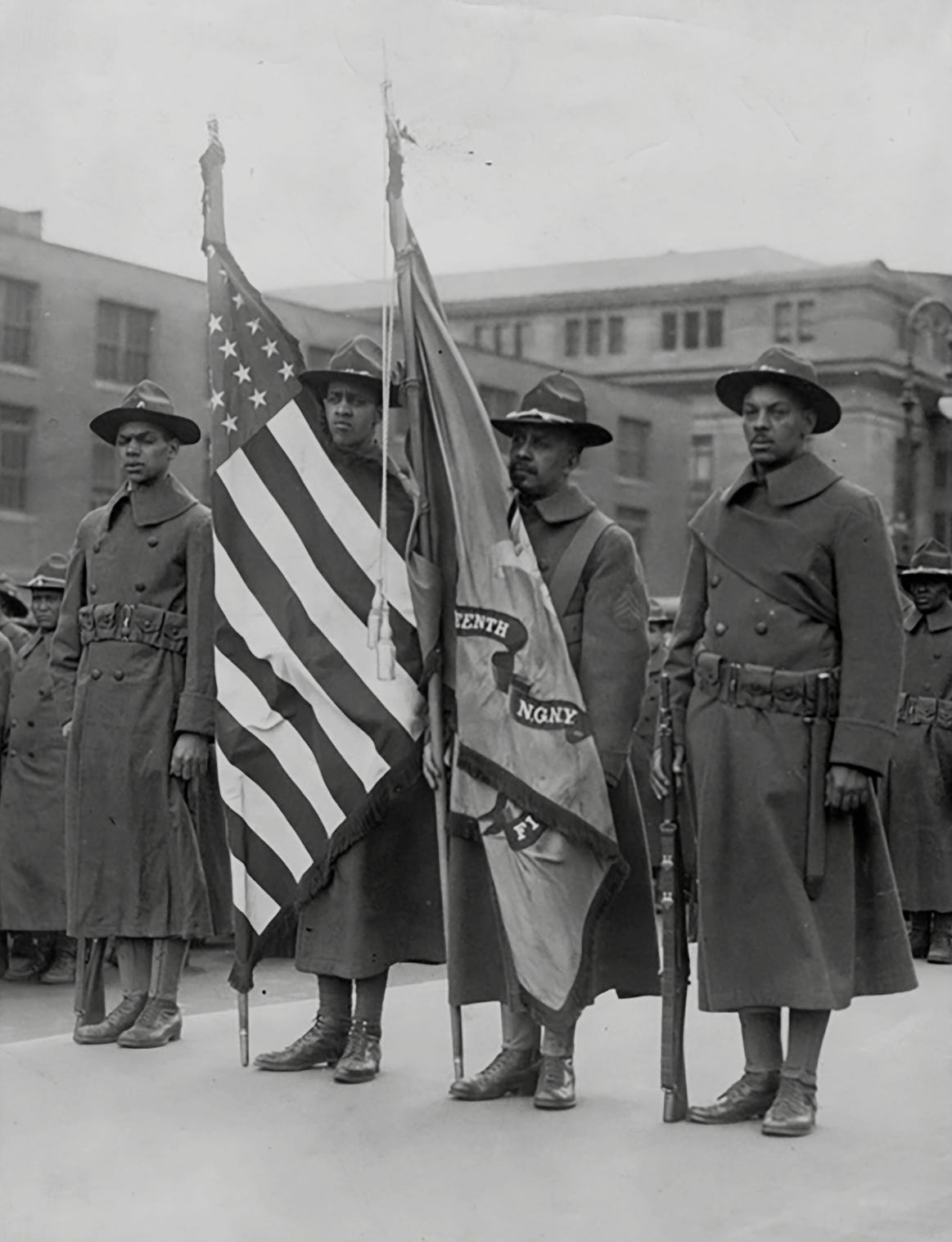

On a crisp February morning in 1919, the broad avenues of New York City pulsed with the rhythm of triumph and pride. “Up the wide avenue they swung,” wrote the New York Tribune in a vivid three-page spread on February 18th, capturing the moment with a flourish. “Their smiles outshone the golden sunlight. In every line proud chests expanded beneath the medals valor had won. The impassioned cheering of the crowds massed along the way drowned the blaring cadence of their former jazz band. The old 15th was on parade, and New York turned out to tender its dark-skinned heroes a New York welcome.”

It was the day before, February 17th, that some 3,000 veterans of the 369th Infantry Regiment—once known as the 15th New York (Colored) Regiment—marched from Fifth Avenue at 23rd Street up to 145th and Lenox, their steps resounding with the weight of history.

They were among the few Black combat regiments to serve in the Great War, and they had earned the prestigious Croix de Guerre from the French army for six months of “brave and bitter fighting.” The Germans, their foes across the scarred fields of Europe, had dubbed them “Hellfighters”—the Harlem Hellfighters—a name that stuck like the rattlesnake adorning their uniforms.

During the war, while in France, the 369th Infantry’s bandmaster, James Reese Europe, wove a different thread of triumph. Before the war, his Clef Club Company Orchestra had electrified Carnegie Hall and beyond, earning rapturous reviews. Inducted into the Army, he was commissioned a lieutenant and named bandmaster of the 369th, the Harlem Hellfighters. Across French cities, his band spread the vibrant pulse of Black American music, a cultural salvo amid the war’s din.

Their nicknames—“Harlem Hellfighters” from the Germans, “Black Rattlers,” and “Men of Bronze” from the French—resounded alongside their motto, “Don’t Tread On Me.” Among them rode Private Henry Johnson of Albany, New York, a hero of singular valor. Wounded in battle, he sat in a car reserved for the injured, yet the fervor of the crowd moved him to rise, waving a bouquet of flowers handed to him in tribute. The steel plate in his foot—a relic of his courage—could not anchor him that day. It would be another 77 years before his government awarded him the Purple Heart, but on this morning, the accolade of the people was enough.

The newspapers captured the scale of the moment with awe. The New York Tribune estimated it to be an astonishing 5 million, while even the more restrained New York Times conceded there were “hundreds of thousands.” It was, they noted, the first chance for New York to greet an entire regiment of returning doughboys, Black or white.

“Never have white Americans accorded so heartfelt and hearty a reception to a contingent of their black country-men,” the Tribune proclaimed. The “ebony warriors” felt it, too, as chocolate candy, cigarettes, and coins rained down from open windows along the route. To the Times, every man seemed to tower seven feet tall, giants in the eyes of a city transfixed.

Yet if the cheers along Fifth Avenue were loud, the Tribune observed, “the greeting the regiment received in Harlem was to the tumult which greeted it in Fifth Avenue as the west wind to a tornado.” Harlem was home to 70 percent of the 369th, and their families, friends, and neighbors turned out in force. Eight hundred of their comrades had not returned, a silent toll marked by the handkerchiefs drying wet eyes along the way.

The journey to this moment had begun that morning with four trains and two ferries, ferrying the Black veterans and their white officers from Camp Upton on Long Island to Manhattan. The parade commenced at 11:00 a.m.—an echo of the armistice that had silenced the guns three months prior—and stretched seven miles through the city. Dignitaries lined the route: Emmett Scott, special adjutant to the secretary of war; William Randolph Hearst; and New York’s beloved Irish Catholic governor, Al Smith, who reviewed his Hellfighters from stands at 60th and 133rd Streets.

In Harlem, the Chicago Defender declared February 17th an unofficial holiday, with Black schoolchildren dismissed by the board of education to join the celebration. That same day, across the nation in Chicago, the Black veterans of the 370th Infantry—the old Eighth Illinois—received a similar welcome, as historian Chad L. Williams records in his work, Torchbearers of Democracy.

In the months to come, even the Jim Crow South paused to honor its returning sons, most notably in Savannah, Georgia—a state that, in 1917 and 1918, had led the nation in lynchings, according to the Tuskegee Institute’s grim tally. It was, to be sure, a singular season, a fleeting interlude between the end of war abroad and the resumption of strife at home, in a nation still cleaved by the color line.

Congress would not enshrine Armistice Day as an official holiday until 1938, nor rename it Veterans Day until 1954. But the people of New York needed no such decree. On February 17, 1919, they poured forth to honor their Black fighting men, crafting what might be called the first “veterans day parade” tied to the armistice—a tribute offered in the month that would one day be dedicated to Black history.

The World Safe for Democracy?

Two years earlier, on April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson had stood before Congress, urging war to ensure “the world must be made safe for democracy.” The nation’s allies—the British, French, and Russians—stood against the Central Powers: Germany, Italy, and Austria-Hungary. Yet, for many African Americans, Wilson’s words rang hollow.

In the summer of 1917, as the United States steeled itself for the Great War, a different battle raged on its soil. On July 2nd, in East St. Louis, a rumor—that a Black man had slain a white man—ignited a tinderbox of racial fury. Nine whites fell, but the toll on Black lives was staggering: hundreds perished, their homes and livelihoods reduced to rubble, with half a million dollars in property damage scarring the city.

Weeks later, on August 23rd, in Houston, Texas, the Black soldiers of the 24th Infantry reached their breaking point. One of their comrades had been beaten and arrested by two white policemen after he tried to halt their arrest of a Black woman. Whispers of an approaching white mob—whether true or not—sent the troops scrambling through their camp for ammunition, driven by a grim axiom: the best defense is a good offense.

Through a driving rain, they marched into Houston, and violence erupted. Fifteen lives were lost—four policemen, a member of the Illinois National Guard among them. Two Black soldiers died in the clash, one turning his weapon on himself, a bullet to the head, rather than risk capture. “Ten men probably ‘could not begin to tell the complete story of what took place that night,’” Army prosecutor Colonel Hull would later reflect, yet in the aftermath, sixty-three faced charges of mutiny, and thirteen were hanged, still clad in their army khakis.

These were the dark currents swirling beneath a nation that, on April 2, 1917, heard President Woodrow Wilson stand before Congress and proclaim, “The world must be made safe for democracy.” The call to arms came three years after an assassin’s bullet felled an archduke in 1914, plunging Europe into chaos. America’s allies—the British, French, and Russians—stood against the Central Powers: Germany, Italy, and Austria-Hungary.

Yet, for many African Americans, Wilson’s words clanged with hypocrisy. This was the man who had screened Birth of a Nation—a film glorifying the Ku Klux Klan—at the White House, who refused a federal anti-lynching bill. At the same time, lynchings averaged more than one a week, predominantly in former Confederate states that had stripped Black men of their voting rights.

“Will some one tell us just how long Mr. Wilson has been a convert to TRUE DEMOCRACY?” the Baltimore Afro-American demanded on April 28, 1917. The Messenger, a Socialist torch lit by editors Chandler Owen and A. Philip Randolph—later of March on Washington fame—cut deeper on November 1st: “Patriotism has no appeal for us; justice has.” Such defiance landed both men in jail under the Espionage Act.

Yet others saw a chance for dual victory—abroad and at home. W.E.B. Du Bois, a founder of the NAACP, penned a now-infamous call in the July 1918 Crisis:

“Let us, while this war lasts, forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our white fellow citizens and the allied nations that are fighting for democracy.”

His words stirred controversy, shadowed by his simultaneous bid for a captaincy, but they echoed a resolve among many. Of the 4.8 million men under arms, 370,000 were African American, drawn from the 2.3 million registered for the draft. The Marines barred their doors; the Navy enlisted a scant few, relegating them to menial roles—stewards and cooks. But the Army opened its ranks, and 375,000 served, including 639 who earned commissions—a historic first, as historian Chad L. Williams records.

In training camps, however, the old prejudices held firm: abuse from white officers, segregation into separate quarters, and assignment to labor battalions shadowed their every step, a bitter echo of civilian life. The Army cleaved its Black troops into two combat divisions, the 92nd and 93rd, for, as Williams writes, “War planners deemed racial segregation, just as in civilian life, the most logical and efficient way of managing the presence of African Americans in the army.”

Of the 200,000 who shipped overseas, only 42,000—11 percent—saw combat, the rest bending their backs in the Services of Supply, hauling, building, sustaining the war machine. In 1917, American troops saw little fighting, save for the 92nd Division, which was thrust into the French army’s lines for 191 days. But by 1918, at Meuse-Argonne, their story turned bitter. The campaign faltered, white and Black troops alike struggling in the mire, yet the 92nd bore the blame.

Five Black officers faced court-martial on trumped-up charges, and white Major J.N. Merrill of the 368th’s First Battalion wrote his superior with venom:

“Without my presence or that of any other white officer right on the firing line I am absolutely positive that not a single colored officer would have advanced with his men. The cowardice showed by the men was abject.”

Though Secretary of War Newton Baker commuted their sentences, the damage was done—the 92nd was pulled from the line, their valor smothered by scapegoating.

Across the Atlantic, a lone figure carved a different path through the skies. Eugene Jacques Bullard, born October 9, 1895, in Columbus, Georgia, to William, a former slave, and Josephine Bullard, knew hardship early. His youth was a litany of flight—multiple runaway attempts, one ending with a beating from his father’s hand when he was dragged home. In 1906, at age 11, he broke free for good, wandering the South for six years in search of liberty.

In 1912, he stowed away on the Marta Russ, a German freighter bound for Hamburg, but fate dropped him in Aberdeen, Scotland. “They treated me just like one of their own,” he later wrote, and within 24 hours, he felt “born into a new world,” his heart open to love again. He made his way to London, where he took odd jobs—street performer, dock-worker, target for an amusement park game, helper on a fish wagon—before finding his fists as a boxer and his stage with Belle Davis’s Freedman Pickaninnies, an African American slapstick troupe. In 1913, a boxing match lured him to Paris, where he stayed. “It seemed to me that French democracy influenced the minds of both black and white Americans there and helped us all act like brothers,” he reflected.

When war erupted in the summer of 1914, Bullard enlisted in the French Foreign Legion’s 170th Infantry Regiment. At Verdun, from February to December 1916, he fought through hell and was seriously wounded, then taken from the battlefield to Lyon to heal. On leave in Paris, he wagered a friend $2,000 that his color wouldn’t bar him from the Aéronautique Militaire. His grit won out—by November 1916, he was training at Tours, earning his wings on May 20, 1917.

Assigned first to Escadrille Spa 93, then Spa 85 in September, he flew until November 1917, claiming two victories—a Fokker Triplane and a Pfalz D.III—though confirmation wavered (some accounts say one was verified). His Spad 7 C.1 bore a heart pierced by a dagger and the words “All Blood Runs Red,” he flew with a Rhesus monkey named Jimmy as his mascot.

When America joined the war in 1917, Bullard sought to fly for the U.S. Air Service, only to be rebuffed—ostensibly because he was an enlisted man, while pilots had to be officers of at least First Lieutenant rank, but indeed because of the racial prejudice that stained the American military. “Some comfort out of knowing that I was able to go on fighting on the same front and in the same cause as other citizens of the U.S.,” he wrote. Yet, a confrontation with a French officer saw him summarily removed from the air in late 1917, and he returned to the 170th Infantry until his discharge in October 1919.

Fearing Nazi capture, he fled through Spain and Portugal, landing in Harlem, New York, by 1940. There, he worked as a security guard and longshoreman, his spirit unbroken but tested. In the summer of 1949, at a Paul Robeson concert in Peekskill, police and a racist mob beat him; later, a bus driver ordered him to the back of his bus. Disillusioned, he returned to France, but his old life was lost. The French, though, never forgot him. In 1954, he was one of three chosen to relight the everlasting flame at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier; in October 1959, he was knighted in the Legion of Honor—his fifteenth decoration from France.

In America, his later years were toil and obscurity. Yet, in 1992, McDonnell Douglas donated a bronze bust by sculptor Eddie Dixon to the National Air and Space Museum, displayed in the Legend, Memory and the Great War in the Air gallery. On September 14, 1994, he was posthumously commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force, a display case in Dayton, Ohio, honoring a man Craig Lloyd, in Eugene Bullard, Black Expatriate in Jazz-Age Paris, called a testament to “the crippling disabilities imposed on the descendants of Americans of African ancestry,” contrasted with his “quarter-century of much-heralded achievement in France.”

This was a singular season, a pause before the color line tightened anew. The 92nd’s scapegoating, Bullard’s wings, Europe’s music, and the violence at home framed the Hellfighters’ triumph in a broader tapestry. They returned with a new sense of themselves, a consciousness that would fuel the civil rights struggles ahead, their legacy a quiet thunder beneath the cheers of that February day.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

"Africana Age: African & African Diasporan Transformations in the 20th Century." Online exhibition. Schomburg Center, New York Public Library. http://exhibitions.nypl.org/africanaage/.

Gubert, Betty Kaplan. "Who Were the Harlem Hellfighters?" The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross, PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/who-were-the-harlem-hellfighters/.

Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. “Eugene J. Bullard.” https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/eugene-j-bullard.

Williams, Chad L. Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010.